Bridging Literacies with Videogames PDF

Preview Bridging Literacies with Videogames

Bridging Literacies with Videogames GAMING ECOLOGIES AND PEDAGOGIES SERIES Volume 1 Series Editors: Hannah R. Gerber, Sam Houston State University, USA Sandra Schamroth Abrams, St. Johns University, USA Editorial Advisory Board: Thomas Apperley, University of Melbourne, Australia Jen Scott Curwood, University of Sydney, Australia Julia Gillen, Lancaster University, UK Jayne Lammers, University of Rochester, USA Jason Lee, The Pennsylvania State University, USA Alecia Magnifico, University of New Hampshire, USA Guy Merchant, University of Sheffield, UK Michael K. Thomas, USA Mark Vicars, Victoria University, Australia Allen Webb, W estern Michigan University, USA Bronwyn Williams, University of Louisville, USA Karen Wohlwend, Indiana University, USA Scope: Research suggests that a majority of today’s students play videogames on a regular basis – five or more times per week. Research also suggests that more attention is needed to understand and theorize the connections among multiple out-of-school literacy practices and academic spaces. There are multiple ways that videogames shape and inform people’s lifeworlds, and this series aims to provide an understanding of gaming ecologies as a means to conceptualize and theorize gaming, learning, and virtual environments. We invite proposals that draw upon a broad range of methodological approaches and theoretical perspectives in order to move the field forward and understand new directions that videogames and MUVEs have in learning experiences. Books in this series may be conceptual, theoretical, and empirical and can be edited compilations, anthologies, single-authored and co-authored texts. We invite interested authors to submit proposals relating to videogames and learning to Hannah R. Gerber, hrg004@shsu.edu or Sandra Schamroth Abrams, abramss@stjohns.edu Bridging Literacies with Videogames Edited by Hannah R. Gerber Sam Houston State University, Texas, USA and Sandra Schamroth Abrams St. John’s University, New York, USA A C.I.P. record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN: 978-94-6209-666-0 (paperback) ISBN: 978-94-6209-667-7 (hardback) ISBN: 978-94-6209-668-4 (e-book) Published by: Sense Publishers, P.O. Box 21858, 3001 AW Rotterdam, The Netherlands https://www.sensepublishers.com/ Printed on acid-free paper All Rights Reserved © 2014 Sense Publishers No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. To my nephews, Andy, Caleb, and Gabe, who inhabit a gaming world that spans many literacies. -Hannah To my husband and our children who continuously remind me of the lessons embedded in play. -Sandra TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ix Allen Webb & Robert Rozema Preface xiii Acknowledgements xv About the Contributors xvii Chapter Abstracts xxi Bridging Literacies: An Introduction 1 Sandra Schamroth Abrams & Hannah R. Gerber Section One: (Re)Creating Worlds and Texts 1. Exploring Imaginary Maps: Collaborative World Building in Creative Writing Classes 11 Trent Hergenrader 2. Students’ Transmedia Storytelling: Building Fantasy Fiction Storyworlds in Videogame Design 29 Ryan M. Rish 3. Reader, Writer, Gamer: Online Role-Playing Games as Literary Response 53 Jen Scott Curwood 4. Teaching with Club Penguin: Re-creating Children’s School Literacy through Paratexts in the Classroom 67 Anne Burke Section Two: Massive Multiplayer Second Language Learning 5. Massively Multiplayer Online Gaming and English Language Learning 91 Jason YJ Lee & Charlotte Pass 6. Language Games: How Gaming Communities Shape Second-Language Literacy 103 Javier Corredor & Matthew Gaydos vii TABLE OF CONTENTS 7. The Transformative Power of Gaming Literacy: What Can We Learn from Adolescent English Language Learners’ Literacy Engagement in World of Warcraft (WoW)? 129 Zhuo Li, Chu-Chuan Chiu, & Maria R. Coady Section Three: Videogames and Classroom Learning 8. Reviewing the Content of Videogame Lesson Plans Available to Teachers 155 Mary Rice 9. Collaborative Videogame and Curriculum Design for Language and Literacy Learning 171 Lan Ngo, Nora A. Peterman & Susan Goldstein 10. Writing in Virtual Worlds: Scratch Programming as Multimodal Composing Practice in the Language Arts Classroom 187 Julie Warner Index 209 viii ALLEN WEBB & ROBERT ROZEMA FOREWORD In W hat Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy (2003), James Gee extracted the strategies and principles that keep videogame players motivated to master increasingly difficult skills and knowledge, strategies and principles that he believed were transferable to many different learning situations. Perhaps what was most ground-breaking about Gee’s work was not the learning strategies he found– many were familiar–but that an academic scholar, a leading expert in linguistics and literacy, approached videogames with a high level of respect for their complexity, their ability to engage participants, and their educational methodology. Gee investigated videogames as new semiotic domains–new contexts for the construction of meaning and the practice of literacy. Bridging Literacies in Videogames draws on Gee’s work, but goes to a different level. The editors and authors here are thinking deeply about the intersection between videogames and learning. But they are also interested in what happens when students develop virtual worlds, design video games, engage in online role play in response to real world issues, and learn language, especially English, in games that transcend culture, class, and nationality. E ven as cultural critics blame videogames for a host of social ills—violence, illiteracy, and antisocial behavior, to name a few—the contributors to this volume are building bridges between the world of videogames and the world of school. Had they been teaching in the late 1960s, the writers included here would likely be listening to the Beatles along with their students, looking for instances of figurative language in “Happiness is a Warm Gun,” even while all around, pastors and politicians decried rock and roll. B ut they teach today, a time when videogames may be more popular than rock and roll. Today, nearly all adolescents play videogames. They play them on smartphones, on media tablets, on laptop and desktop computers, and on standalone gaming consoles such as the Xbox or PlayStation. They play them alone, with three or four friends, or with thousands of others. They may be building intricate worlds in Minecraft , stealing and joyriding cars in G rand Theft Auto V , completing dangerous missions in C all of Duty , or simply wandering the vast realm of Skyrim . And gamers themselves no longer fit a stereotype: many are indeed teenage boys, but videogames are also increasingly popular with girls, with older people, and with young children. Rob’s son Aidan began playing the Nintendo Wii at age five, delighting in the whimsical worlds offered by L ego Wii games. In L ego Star Wars , Aidan found an immersive galaxy, stocked with familiar characters and settings but ix

The list of books you might like

The Strength In Our Scars

The 48 Laws of Power

Atomic Habits James Clear

Rich Dad Poor Dad

Totemismo hoje

Del profumo dei croissants caldi e delle sue conseguenze sulla bontà umana. 19 rompicapi morali

Svoboda-1995-180

DTIC ADA518756: Reforming Pentagon Decisionmaking

Did I Mention I Miss You?

DISCOVERY OF SUBULARIA-AQUATICA L IN COLORADO AND THE EXTENSION OF ITS RANGE

Enterprise DevOps for Architects

Little Snap The PostBoy by Victor St Clair mdash

Town of Stoneham Annual Report

International Journal of Coal Geology 1993: Vol 24 Table of Contents

Statistical Challenges for Searches for New Physics at the LHC

Greek Government Gazette: Part 2, 1993 no. 423

MODERN MICROECONOMICS THEORY AND APPLICATIONS

Greek Government Gazette: Part 2, 1993 no. 473

Caldaia murale a gas ad alto rendimento

IS 8963: Chlorpyrifos, Technical

Review and Expositor 2006: Vol 103 Index

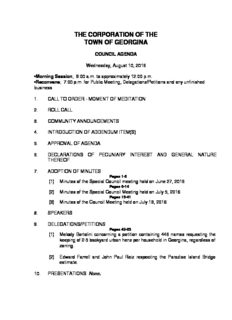

Allow Backyard Chickens In Georgina ON