Table Of ContentVintage Tomorrows

James H. Carrott and Brian David Johnson

VINTAGE TOMORROWS

by James H. Carrott and Brian David Johnson

Copyright © 2013 James H. Carrott and Brian David Johnson. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online

editions are also available for most titles (http://my.safaribooksonline.com). For more information,

contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or [email protected].

Editors: Brian Jepson and Courtney Nash Proofreader: Christopher Hearse

Production Editor: Christopher Hearse Indexer: Judith McConville

Copyeditor: O’Reilly Publishing Services Cover Designer: Edie Freedman

Interior Designer: David Futato

Illustrator: Rebecca Demarest

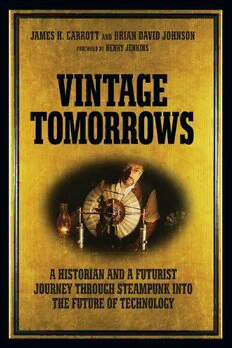

Cover photos courtesy of Jake von Slatt, who also built the devices pictured and who appears in the front cover

image.

February 2013: First Edition

Revision History for the First Edition:

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781449337995 for release details.

Nutshell Handbook, the Nutshell Handbook logo, and the O’Reilly logo are registered trademarks

of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Vintage Tomorrows and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media,

Inc.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are

claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O’Reilly Media, Inc.,

was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps.

While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and authors

assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the

information contained herein.

ISBN: 978-1-449-33799-5

[LSI]

James: To Amelia and Beatrix.

Both the future and the past are in your hands. Don’t believe “can’t.” Take leaps of

faith. Never choose an answer over a question. And make it better.

Brian: To James H. Carrott.

This book began with him and he has been the heart and soul of Vintage Tomor-

rows throughout the entire project. Thank you James! You are a gentleman and a scholar

and it’s been a pleasure collaborating with you.

Contents

Foreword: Any | vii

Questions?

Prologue | xvii

1 | A Futurist and a Cultural Historian Walk into a Bar 1

2 | Beats, Pranksters, Hippies, Steampunks! 15

3 | Technology That Ships Broken 47

4 | A World-Destroying Death Ray Should Look Like a World-

Destroying Death Ray 67

5 | Steampunk: A Dinner in Three Courses 87

PRELUDE | A Note from the Historian 117

6 | It’s About Chickens and Teapots 119

7 | Digging Into the Past 147

8 | History Has Sharp Edges 175

v

vi | CONTENTS

9 | Punking Time in Key West 207

10 | The Answer’s in Our Own Backyard 231

11 | Makers and Burners 255

12 | Pop Goes Steampunk 279

PRELUDE | A Note from the Futurist 289

13 | Humor Is the New Killer App 291

14 | Don’t Forget the Humans 309

15 | When Is an iPhone Like a Pocket Watch? 323

16 | We Must Design a Better Future 337

17 | Humanity in the Machine 351

18 | We Want to Remember a Time When Our Lives Were Not

Made of Plastic 367

19 | What’s Next? 379

A | Image Credits 385

Index 387

Foreword: Any

Questions?

Henry Jenkins

Vintage Tomorrows started as a conversation between a cultural historian and a fu-

turist: what might steampunk (as a genre, movement, lifestyle, and philosophy)

teach us about the ways people are thinking about their relationships with tech-

nology? They found it a gripping topic, they set out to talk with others, and the

conversation kept broadening outward, as they found more thinking partners,

many of whom were already talking through these questions together, and as one

question led to another and another…

Christopher Columbus sailed west to get east; these authors looked into our

collective fantasies about the past (or rather yesterday’s tomorrows) in order to bet-

ter understand our shared desires for the future. Ultimately, the authors hope peo-

ple will design and build better tools because we have a deeper understanding of

what makes technologies meaningful for people who spend a lot of time re-

imagining and retrofitting 19th century devices and gadgets. Makes sense to me.

I have been researching fan cultures for more than thirty years and participat-

ing in them for much longer, so let me put steampunk into a larger context. I am

going to be painting with pretty broad strokes, so bear with me. Like the authors, I

think something profound is going on here. Vintage Tomorrows compares it with

the “counter-cultures” of the 1960s and I can follow them there. After all, as tech-

nology historian Fred Turner has suggested, the counterculture was the birthplace

of today’s cyberculture. For me, the explanation for all of this starts elsewhere—

with the origins of science fiction and of science fiction fandom, both of which have

in turn influenced contemporary forms of participatory culture.

The first thing you need to understand is that science fiction fandom has always

been a community of people who were drawn together because they wanted to ask

questions and most of the people around them found this constant probing to be

annoying. The community’s conversation started in the early part of the 20th cen-

vii

viii | Foreword: Any Questions?

tury and hasn’t slowed down since. Fandom doesn’t simply exist to give fans a

chance to talk with each other about the stories they enjoy. Science fiction stories

exist to give fans something to talk about with each other. Speculation is the name

of the game, and fans play that game better than anyone else.

The second thing you need to understand is that whatever steampunk is (and

you will get lots of definitions here), it isn’t “Victorian science fiction.” If you asked

Victorians about science fiction, they would not have a clue what you were talking

about, though science fiction as a genre was profoundly and permanently shaped

by the Victorian imagination. While many Victorians desperately wanted to believe

in the stability of the empire and the power of tradition to give order and meaning

to their lives, they were actually living at a moment of profound and prolonged

change. One reason we are so preoccupied with the Late Victorian period, today, is

that it may have been the last time, prior to the digital revolution, when our society

confronted such a dramatic shift in its basic technological infrastructure. “New

media” is a state of mind; every “old” media was “new” once, and people had to

confront the changed realities that those new technologies might on the ways they

saw the world. One way we cope with the shock of the new is to look backwards,

hoping that the shock of the old might counteract its impact. So, the digital revo-

lution has invited us to reconsider “The Victorian Internet,” as Tom Standage de-

scribed the Telegraph, and a range of other devices that look differently to us today

thanks to our access to networked computers. Steampunk represents one of a

number of new kinds of historical consciousness that are emerging as people try

to put themselves in the places of previous generations as they underwent a media

revolution.

Literary critic Jay Clayton’s delightful book, Charles Dickens in Cyberspace: The

Afterlife of the Nineteenth Century in Postmodern Culture, explores many different

connections people have drawn between the Victorian age and our own. Contrary

to common stereotypes about rigid Victorian thinking, Clayton argues that the late

19th century was characterized by “undisciplined culture”: “[The 19th century

thinkers] thrived in an atmosphere that might be described as predisciplinary, a

world in which the professional characteristics of science as a discipline had not

yet been codified…These men and women had an irreverent attitude towards

boundaries and an impatience with anything resembling intellectual restraint. They

mixed science, engineering, and the arts as they pleased. Without too much exag-

geration, they might be described as the nineteenth-century equivalent of hackers.”

The Victorians witnessed dramatic changes in the technologies of transporta-

tion and production, but for my purposes, what seems most interesting is that there