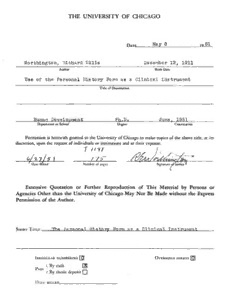

Table Of ContentTHE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

DATF. May 8 51

lQ

Worthington, Richard Ellis December 12, 1911

Author Birth Date

Use of the Personal History Form as a Clinical Instrument

Title of Dissertation

Human Development Ph.D* June, 1951

Department or School Degree Convocation

Permission is herewith granted to the University of Chicago to make copies of the above title, at its

discretion, upon the request of individuals or institutions and at their expense.

6 / 2 - 7 / 5- / /7JT /vfM/*lfa

-vt^vr,

Date filmed Number of pages Signature of'author

Extensive Quotation or Further Reproduction of This Material by Persons or

Agencies Other than the University of Chicago May Not Be Made without the Express

Permission of the Author.

SHORT TITLE :___Ihfi Prrannfll History Fo-rm HB P. OUniMl Instrument

IRREGULAR NUMBERING (3 OVERSIZED SHEETS \U\

_ \ By cash [5j

PAID - . . .__.

/ Jiy thesis deposit |_J

DATE BILLED

THE UNIVERSITY OP CHICAGO

USE OP THE PERSONAL HISTORY PORM

AS A CLINICAL INSTRUMENT

A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO

THE FACULTY OP THE DIVISION OP THE SOCIAL SCIENCES

IN CANDIDACY POR THE DEGREE OP

DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY

HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

BY

RICHARD ELLIS WORTHINGTON

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

JUNE, 1951

FOREWORD

, Each Individual will bring to this dissertation his

own knowledge and wisdom which can make a critical reading

the more valuable. Gaps and Inadequacies in the author's

presentation may be distinctly evident; and these, it is

hoped, will inspire the reader himself to do more fruitful

work. Much of what is written is not new, some little is.

And the little may not be stimulating; but if it does give

rise to one single new idea in the reader, then the writer

of this thesis will think of the effort that went into it

as having been worth while.

No whole man lives to himself, nor is he sufficient

unto himself. That real and vibrant component called wife

can make the difference between happiness and all the poor

substitutes that are the lot of incomplete man. In full

knowledge of the experience of happiness through my wife,

whose constant love and companionship, aid and encourage

ment led me on with this work, I take this opportunity to

bless her for finding in me the genesis of the man I am

become.

Friends, too, are an integral part of man's whole

ness; and among the many I have to thank for their support,

those adding most to my "totalness" by their actions are:

Professors Robert J. Havighurst, Hedda Bolgar, W. Lloyd

Warner,- Carl R. Rogers, J. Carson McGulre, William E. Henry,

William 0. Stephenson; Doctors James G. Miller, Burleigh B.

Gardner; and Clara Weimer, Douglas M. More, Robert F. Peck,

Gllmore J. Spencer, Mildred L. Schwartz, Cnarles M. Wharton,

and Harriett Moore. Of them all, to Harold C. Trownsell,

whose unshakeable belief in the outcome of the study was a

constant stimulation, is owed perhaps the place next to my

wife.

ii

Teachers, too, are to be thanked for the role they

played in the author's reaching that part of this study

that may prove a mature expression. Among them I would

particularly list Professors Helen L. Koch, Wilton M. Krog-

man, Nathan Kleltman, Prank S. Freeman, Louis Wlrth, Anton

J. Carlson, Robert Redfleld, Ernest W. Burgess; and Doctors

Karl A. Mennlnger, Mandel Sherman, and Dael Wolfle.

To my family go thanks for paving the way for a

reasonable amount of personal growth and development.

Ill

TABLE OP CONTENTS

Page

FOREWORD ii

LIST OP TABLES vi

LIST OP ILLUSTRATIONS viii

Chapter

I. STATEMENT OP THE PROBLEM 1

Historical Background 3

Some Operational Hypotheses and

Observations about Personality 7

Notes on Our Industrial Society and

Its Relationship to Personality

Structure 10

Our Industrial Society and Its Rela

tionship to Personality Structure . . .. 15

Personality as a Process 16

II. THE INSTRUMENT, SCORES AND PRINCIPLES OP

SCORING, THE PROFILE, AND TECHNIQUE OP

INTERPRETATION 25

Introduction 25

The Personal History Form 25

Administration 30

Accuracy of Responses 32

Scoring Categories 32

Scoring Principles and Assignment of

Scores 3^

Assessment of Defense Mechanisms and

Scoring HQ

Character Structure Indicators 51*

Facets of Personality 58

Scoring for School Subjects, Hobbies,

and Interests 62

The Profile and Technique of

Interpretation 73

iv

TABLE OP CONTENTS--Continued

Chapter Page

III. ASSUMPTIONS, TECHNIQUES, AND PROCEDURES

OP THE PERSONAL HISTORY METHOD AS DEMON

STRATED IN A SINGLE CASE 85

Behavior and Interpretation 86

Face Sheet Summary and Tentative

Conclusions 91

Physical Data Summary and Tentative

Conclusions 9^

Summary of Educational Area and

Tentative Conclusions 100

Summary of Activities Area and

Tentative Conclusions 102

Summary of Present Business Experience

and Tentative Conclusions 104

Summary of Job History and Tentative

Conclusions 110

Summary of Alms and Tentative Conclusions . 112

IV. DESIGN OP THE RESEARCH AND FINDINGS 128

General Procedure 129

Three Additional Cases 132

The Findings 133

V. CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS 155

Practical Implications of the Research . . . l6l

BIBLIOGRAPHY 164

i

v

LIST OP TABLES

Page

Tabulation of Clinicians* and Psychotherapists*

Ratings of Agreement for Group I Cases by

Descriptive Categories 135

Numbers of Items in Each Category of Agreement

for Each Clinician and Psychotherapist . . .. 138

Chl-Square Test of Differences Between

Clinicians and Psychotherapists on Columns

1, 2, 3, and 4 of Table 2 139

Numbers and Percentages of Agree, Disagree,

and Not Covered, by Categories for Eight

Cases in Group I 139

Total Ratings of Clinician and Psychotherapist

in Group I in which Inferred Agreement or Dis

agreement Has Been Eliminated from the Not

Covered Colums and Placed in the Agree-Disagree

Columns 1*11

Significance of the Difference Between Clini

cians and Psychotherapists in Rating Personal

ity Dynamics (Group I Cases) 142

Significance of the Difference Between Clini

cians and Psychotherapists in Rating Character

Structure (Group I Cases) 143

Significance of the Difference Between Clini

cians and Psychotherapists in Rating Intellec

tual Capacities (Group I Cases) 145

Significance of the Difference Between Clini

cians and Psychotherapists in Rating Behavior

al Picture (Group I Cases ) 146

Significance of the Difference Between Clini

cians and Psychotherapists in Rating Diagnosis

(Group I Cases) 148

Significance of the Difference Between Clini

cians and Psychotherapists in Rating Prognosis

(Group I Cases) 149

vi

LIST OP TABLES--Continued

Page

Differences Between Clinicians and Psycho

therapists for Group I Cases with respect

to Agree, Disagree, and Not Covered Cate

gories . . . .""" 150

Tabulation of Clinicians1 and Psychothera

pists' Ratings of Agreement for Group II

Cases by Descriptive Categories 151

Numbers and Percentages of Agree, Disagree,

and Not Covered for the Categories Over All

Eleven Cases 152

vii

LIST OP ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure Page

1. Schema of Some Facts, Situations, and

Processes Basic to Differing Degrees

of Goodness of Prediction 22

2. Personal History Form 26

3. Personal History—Scoring Record 74

4. Profile 75

5. Profile of Lower Middle Class Woman 79

6. Profile of Upper Lower Class Man 80

7. Profile of Upper Middle Class Woman 81

8. Profile of Lower Middle Class Man 82

9. Profile of Upper Middle Class Man 83

10. Profile of Upper Middle Class Man 84

11. Completed Personal History Form 113

12. Completed Profile of Case History 117

13. Psychological Report 120

viii

CHAPTER I

STATEMENT OP THE PROBLEM

This dissertation will concern Itself with an In

tensive attempt to develop a methodological approach to the

use of an application blank as a projective instrument to

assess personality.

Broadly speaking, there are two main classes of in

struments for gaining insight into personality. These are

the outcomes of distinctive points of view. Differential

psychology has approached the problem in much the same way

as was found successful in measuring intelligence. Aspects

of personality have been defined which are ascertained

through pencil and paper scales made up of items calling

for the subject's reactions to situations of everyday life.

Norms have been determined which enable the tester to de

scribe personality as a degree of conformity to them.

Among criticisms of this approach, two of the more important

seem to be that the subject can consciously manipulate his

responses, and that the subject's scores may tell nothing

of the ways in which aspects of his personality are inte-

grated.

The other main group of measures have been developed

on the assumptions underlying clinical psychology and psy

chiatry in which aspects of personality have greatest mean

ing in their relationships to one another within the indi-

vidual. These measures, the so-called projective tech-

L. K. Prank, "Projective Methods for the Study of

Personality," Journal of Psychology. VIII (1939), 393.

2

Lee J. Cronbach, Essentials of Psychological Test

ing (New York: Harper and Brothers, 19^9)/ p. ^33.

3prank, OP. cit.. p. 392.

1