Table Of ContentTHE SELECTED LETTERS OF

Anthony Hecht

(cid:2)

(cid:2)

(cid:2)

THE SELECTED LETTERS OF

Anthony Hecht

Edited with an introduction by

JONATHAN F. S. POST

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS

Baltimore

© 2013 The Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2013

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All letters by Anthony Hecht © 2013 The estate of Anthony Hecht.

The Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hecht, Anthony, 1923–2004.

[Correspondence. Selections]

The selected letters of Anthony Hecht / edited with an introduction by Jonathan F. S. Post.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4214-0730-2 (hdbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-4214-0785-2 (electronic) —

ISBN 1-4214-0730-2 (hdbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 1-4214-0785-X (electronic)

1. Hecht, Anthony, 1923–2004—Correspondence. 2. Poets, American—20th century—

Correspondence. I. Post, Jonathan F. S., 1947– II. Title.

PS3558.E28Z48 2013

811(cid:2).54—dc23

[B] 2012012914

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

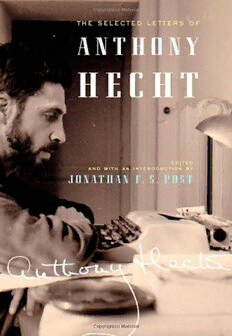

Frontispiece. Anthony Hecht, late 1960s, around the time that he received the Pulitzer Prize

for The Hard Hours. (Courtesy of Helen Hecht)

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please

contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or [email protected].

The Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including

recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever

possible.

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations vii

Introduction ix

Brief Chronology xxi

1 Childhood and College, 1935–1943 3

2 World War II, 1943–1946 19

3 Back Home and Abroad, 1946–1952 69

4 Marriage and Single Life, 1954–1967 101

5 A Second Life, 1968–1982 131

6 Critic and Poet, 1983–1992 203

7 The Flourish of Retirement, 1993–2004 249

Acknowledgments 347

Credits 349

Index 351

This page intentionally left blank

ILLUSTRATIONS

Anthony Hecht, age 13, at Camp Kennebec, Maine, 1936 2

Ninety-seventh Regiment in Czechoslovakia, spring 1945 18

Troop train, postwar France, 1945 59

Anthony Hecht, age 24, University of Iowa, 1947 68

Anthony Hecht, in his study at the American Academy in Rome, 1954–1955 100

Helen D’Alessandro, 1971 130

Anthony Hecht, James Merrill, among others, for T. S. Eliot Centennial Celebration

in St. Louis, 1988 202

Copy of original letter with elaborate letterhead, typical of the kind used by Hecht

in his exchanges with William MacDonald 212

Anthony Hecht, in front of the New York Public Library, 1995 248

Edward Simmons, Willard Metcalf, Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, Robert Reid;

William Merritt Chase, Frank W. Benson, Edmund C. Tarbell, Thomas W. Dew-

ing, Joseph R. DeCamp 270

Following page 128

Melvyn and Dorothy Hecht, ca. mid-1950s

Roger Hecht, late 1930s

Anthony Hecht, Ingrid North (wife of the artist Philip North), and Robie

Macauley, University of Iowa, 1947

Hecht in Ischia, 1951, with Elsa Rosenthal and Irving and Anne Weiss

Patricia Harris Hecht, Ischia, 1954–1955

Anthony Hecht, at a café in Europe, late 1960s

Evan Alexander Hecht, age 5, and father, 1977, Rochester, New York

With sculptor friend Dimitri Hadzi, in the Hecht back yard, Washington, D.C., ca.

early 2000s

Chip Kidd, J. D. McClatchy, Anthony Hecht, and Kathleen Ford, 1998, on the occa-

sion of his 75th birthday

Anthony Hecht, Nicholas Christopher, Edward Hirsch, and Joel Conarroe,

92nd St. Y, 2003

Helen and Tony Hecht, New York City, 1998, on the occasion of his 75th birthday

vii

This page intentionally left blank

INTRODUCTION

In one of the characteristically amusing observations

that makes reading his letters so enjoyable, Anthony Hecht remarked to his

friend and English editor, the poet Jon Stallworthy:

It occurs to me that in the murky future, when it has been at length de-

termined that I am a poet of suffi cient interest to merit the publication of

a volume of “Selected Letters,” the editor of that book will be at a loss to

convey what may, in the last analysis, be the most sprightly, various, and

original part of my correspondence: my letter paper. (December 22, 1976)

What is characteristic about the humor here is the note of self-deprecation in

Hecht’s gradually, tellingly unfolding syntax. Initially imagining, with some

small effort, a time in the murky future when his letters might be deemed worth

collecting, the author manages to prick the puffery of this thought—although

not before nicely amplifying it with three well-chosen adjectives—with the

admission that the most valuable thing about his letters is the stock they are

written on. How seriously are we meant to take the claim, we wonder? Not

terribly. After all, Hecht only says what “may” be the case in the future. But

the momentarily modest gesture has done its work. It disarms the passage

of its potentially heavy freight involving posterity and lets us enjoy the airy

possibility that his stationery is more valuable than his thinking, even as we

smile over the sprightly claim that thought on paper has produced.

Hecht was speaking in this letter about nothing less than a duel to the fi n-

ish with his friend and arch epistolary rival William MacDonald, the Roman

architectural historian. The subject involved which of the two could come up

with the rarest letterhead; and while MacDonald had an initial professional

advantage, his work taking him to many distant lands, the more geographi-

cally circumscribed Hecht still had some tricks up his sleeve. He employed

friends (“spies” as he calls them) to bring back stationery from all sorts of

exotic and unusual places, even the White House. At one point, Hecht sur-

ix