Table Of ContentCopyright

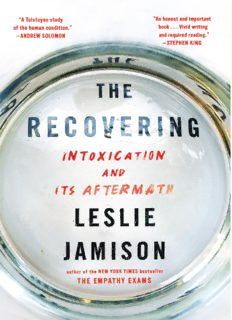

Copyright © 2018 by Leslie Jamison

Cover design and art by Allison J. Warner

Author photograph by Beowulf Sheehan

Cover © 2018 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright.

The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative

works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of

the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the

book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank

you for your support of the author’s rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: April 2018

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little,

Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the

publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To

find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-25962-0

E3-20180308-JV-PC

For anyone addiction has touched

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

I Wonder

II Abandon

III Blame

IV Lack

V Shame

VI Surrender

VII Thirst

VIII Return

IX Confession

X Humbling

XI Chorus

XII Salvage

XIII Reckoning

XIV Homecoming

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Leslie Jamison

Notes

Bibliography

Newsletters

—I—

WONDER

T

he first time I ever felt it—the buzz—I was almost thirteen. I didn’t vomit or black

out or even embarrass myself. I just loved it. I loved the crackle of champagne, its hot

pine needles down my throat. We were celebrating my brother’s college graduation, and

I wore a long muslin dress that made me feel like a child, until I felt something else:

initiated, aglow. The whole world stood accused: You never told me it felt this good.

The first time I ever drank in secret, I was fifteen. My mom was out of town. My

friends and I spread a blanket across living room hardwood and drank whatever we

could find in the fridge, Chardonnay wedged between the orange juice and the

mayonnaise. We were giddy from a sense of trespass.

The first time I ever got high, I was smoking pot on a stranger’s couch, my fingers

dripping pool water as I dampened the joint with my grip. A friend-of-a-friend had

invited me to a swimming party. My hair smelled like chlorine and my body quivered

against my damp bikini. Strange little animals blossomed through my elbows and

shoulders, where the parts of me bent and connected. I thought: What is this? And how

can it keep being this? With a good feeling, it was always: More. Again. Forever.

The first time I ever drank with a boy, I let him put his hands under my shirt on the

wooden balcony of a lifeguard station. Dark waves shushed the sand below our

dangling feet. My first boyfriend: He liked to get high. He liked to get his cat high. We

used to make out in his mother’s minivan. He came to a family meal at my house fully

wired on speed. “So talkative!” said my grandma, deeply smitten. At Disneyland, he

broke open a baggie of withered mushroom caps and started breathing fast and shallow

in line for Big Thunder Mountain Railroad, sweating through his shirt, pawing at the

orange rocks of the fake frontier.

If I had to say where my drinking began, which first time began it, I might say it

started with my first blackout, or maybe the first time I sought blackout, the first time I

wanted nothing more than to be absent from my own life. Maybe it started the first time

I threw up from drinking, the first time I dreamed about drinking, the first time I lied

about drinking, the first time I dreamed about lying about drinking, when the craving

had gotten so deep there wasn’t much of me that wasn’t committed to either serving or

fighting it.

Maybe my drinking began with patterns rather than moments, once I started

drinking every day. Which happened in Iowa City, where the drinking didn’t seem

dramatic and pronounced so much as encompassing and inevitable. There were so many

ways and places to get drunk: the fiction bar in a smoky double-wide trailer, with a

stuffed fox head and a bunch of broken clocks; or the poetry bar down the street, with

its anemic cheeseburgers and glowing Schlitz ad, a scrolling electric landscape: the

gurgling stream, the neon grassy banks, the flickering waterfall. I mashed the lime in

my vodka tonic and glimpsed—in the sweet spot between two drinks and three, then

three and four, then four and five—my life as something illuminated from the inside.

There were parties at a place called the Farm House, out in the cornfields, past

Friday fish fries at the American Legion. These were parties where poets wrestled in a

kiddie pool full of Jell-O, and everyone’s profile looked beautiful in the crackling light

of a mattress bonfire. Winters were cold enough to kill you. There were endless

potlucks where older writers brought braised meats and younger writers brought plastic

tubs of hummus, and everyone brought whiskey, and everyone brought wine. Winter

kept going; we kept drinking. Then it was spring. We kept drinking then, too.

S

itting on a folding chair in a church basement, you always face the question of how to

begin. “It has always been a hazard for me to speak at an AA meeting,” a man named

Charlie told a Cleveland AA meeting in 1959, “because I knew that I could do better

than other people. I really had a story to tell. I was more articulate. I could dramatize it.

And I would really knock them dead.” He explained the hazard like this: He’d gotten

praised. He’d gotten proud. He’d gotten drunk. Now he was talking to a big crowd

about how dangerous it was for him to talk to a big crowd. He was describing the perils

of an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting to a meeting of Alcoholics Anonymous. He was

being articulate about being articulate. He was dramatizing what the art of dramatizing

had done to him. He said: “I think I got tired of being my own hero.” Fifteen years

earlier, he’d published a best-selling novel about alcoholism while sober. But he

relapsed a few years after it became a bestseller. “I’ve written a book that’s been called

the definitive portrait of the alcoholic,” he told the group, “and it did me no good.”

It was only after five minutes of talking that Charlie finally thought to begin the way

others began. “My name is Charles Jackson,” he said, “and I’m an alcoholic.” By

coming back to the common refrain, he was reminding himself that commonality could

be its own saving grace. “My story isn’t much different from anyone’s,” he said. “It’s

the story of a man who was made a fool of by alcohol, over and over and over, year

after year after year, until finally the day came when I learned that I could not handle

this alone.”

The first time I ever told the story of my drinking, I sat among other drinkers who no

longer drank. Ours was a familiar scene: plastic folding chairs, Styrofoam cups of

coffee gone lukewarm, phone numbers exchanged. Before the meeting, I had imagined

what might happen after it was done: People would compliment my story or the way I’d

told it, and I’d demur, Well, I’m a writer, shrugging, trying not to make too big a deal

out of it. I’d have the Charlie Jackson problem, my humility imperiled by my

storytelling prowess. I practiced with note cards beforehand, though I didn’t use them

when I spoke—because I didn’t want to make it seem like I’d been practicing.

It was after I’d gone through the part about my abortion, and how much I’d been

drinking pregnant; after the part about the night I don’t call date rape, and the etiquette

of reconstructing blackouts; after I’d gone through the talking points of my pain, which

seemed like nothing compared to what the other people in that room had lived—it was

somewhere in the muddled territory of sobriety, getting to the repetitions of apology, or

the physical mechanics of prayer, that an old man in a wheelchair, sitting in the front

row, started shouting: “This is boring!”

We all knew him, this old man. He’d been instrumental in setting up a gay recovery

community in our town, back in the seventies, and now he was in the care of his much

younger partner, a soft-spoken book lover who changed the man’s diapers and wheeled

him faithfully to meetings where he shouted obscenities. “You dumb cunt!” he’d called

out once. Another time he’d held my hand for our closing prayer and said, “Kiss me,

wench!”

He was ill, losing the parts of his mind that filtered and restrained his speech. But he

often sounded like our collective id, saying all the things that never got said aloud in

meetings: I don’t care; this is tedious; I’ve heard this before. He was nasty and sour and

he’d also saved a lot of people’s lives. Now he was bored.

Other people at the meeting shifted uncomfortably in their seats. The woman sitting

beside me touched my arm, a way of saying Don’t stop. So I didn’t. I kept going—

stuttering, eyes hot, throat swollen—but this man had managed to tap veins of primal

insecurity: that my story wasn’t good enough, or that I’d failed to tell it right, that I’d

somehow failed at my dysfunction, failed to make it bad or bold or interesting enough;

that recovery had flatlined my story past narrative repair.

When I decided to write a book about recovery, I worried about all of these possible

failures. I was wary of trotting out the tired tropes of the addictive spiral, and wary of

the tedious architecture and tawdry self-congratulation of a redemption story: It hurt. It

got worse. I got better. Who would care? This is boring! When I told people I was

writing a book about addiction and recovery, I often saw their eyes glaze. Oh, that book,

they seemed to say, I’ve already read that book.

I wanted to tell them that I was writing a book about that glazed look in their eyes,

about the way an addiction story can make you think, I’ve heard that story before,

before you’ve even heard it. I wanted to tell them I was trying to write a book about the

ways addiction is a hard story to tell, because addiction is always a story that has

already been told, because it inevitably repeats itself, because it grinds down—

ultimately, for everyone—to the same demolished and reductive and recycled core:

Desire. Use. Repeat.

In recovery, I found a community that resisted what I’d always been told about

stories—that they had to be unique—suggesting instead that a story was most useful

when it wasn’t unique at all, when it understood itself as something that had been lived

before and would be lived again. Our stories were valuable because of this redundancy,

not despite it. Originality wasn’t the ideal, and beauty wasn’t the point.

When I decided to write a book about recovery, I didn’t want to make it singular.

Nothing about recovery had been singular. I needed the first-person plural, because

recovery had been about immersion in the lives of others. Finding the first-person plural

meant spending time in archives and interviews, so I could write a book that might

work like a meeting—that would place my story alongside the stories of others. I could

not handle this alone. That had already been said. I wanted to say it again. I wanted to

write a book that was honest about the grit and bliss and tedium of learning to live in