Table Of ContentPelican Books zr" \

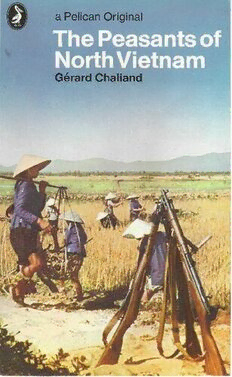

The Peasants of North Vietnam \

\ \

Girard Chaliand, history teacher and specialist

in underdeveloped countries, was bom in Brussels

in 1934, although he is now a French citizen. He '

studied at the National School of Oriental

Languages in Paris. Formerly editor and assistant

manager of the Algerian weekly Revolution

Africaine (1963), Girard Chaliand is the author of

L?Algeria est-all'a sodaliste ? (1964) and Lutte armie '

an Afriqua (1967; Armed Struggle in Africa, 1969).-

In October-November 1967 he made a study of '

several villages in North Vietnam, and on his ■

return published a report in the Monde

Diplomatique. Between the years 1952-62 and r

1966-9 he travelled' extensively in Africa, Latin

America, Middle-east and South-east Asia. J

Gerard Chaliand

The Peasants of

North Vietnam

With a preface by Philippe Devillers

Translated by Peter Wiles

Penguin Books

Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

Penguin Books Inc., 7x10 Ambassador Road, Baltimore, Maryland 21207, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

Les Paysans du nord-vietnam et la guerre first published by F. Maspero 1968

This translation first published in Pelican Books 1969

Copyright© Librairie Francois Maspero, 1968

Translation copyright © Penguin Books Ltd, 1969

Made and printed in Great Britain by

Hazell, Watson & Viney, Aylesbury, Bucks.

Set in Monotype Plantin

This book is sold subject to the condition that

it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent,

re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without

the publisher’s prior consent in any form of

binding or cover other than that in which it is

published and without a similar condition

including this condition being imposed on the

subsequent purchaser

Contents

Preface by Philippe Detrillers 7

Author’s Preface 13

Introduction 16

General 37

The Structure of Vietnam 38

Educational Problems 47

Health Problems 50

The Origins of Escalation 52

Escalation 56

State and Village 58

The Role of Women 60

Democratization at the Bottom 61

The Red River Delta 65

1. The Province of Hung Yen 71

The Province of Hung Yen 88

The Village of Quoc Tri 90

Education 102

' The Work of an Administrative Committee 118

The Organization of a Co-operative 122

A District Hospital 128

Trading 132

Personal Statements 137

2. The Province of Thai Birth 163

Village Caches 170

A Village Medical Unit 172

The Co-operative at Tan Phong 174

The Slaughter of Dai Lai 180

6 Contents

3. The Province of Ha Tay 199

The Commune of Hoa Xa 200

A Handicrafts Co-operative 204

A Bombed Village 207

A Nursery School 211

Personal Statements 215

4. The Province of Nin Binh 229

The Hamlet of Huong Dao 236

The Village of Luu Phuong 239

Conclusion 241

The Role of Ideology 241

Select Bibliography 243

Maps 246-7

Preface

by Philippe Devillers

What can explain the extraordinary resilience with which

Vietnam is countering the' pressure of the American war

machine? How has this nation of thirty-two million men,

women and children, poor and more or less unindustrialized,

managed to survive the torrent of fire and steel to which it has

been subjected for nearly eight years by the most formidable

military apparatus the world has ever known? This is the

question which Gerard Chaliand set out to answer during a

visit to Vietnam in the autumn of 1967 - a visit largely devoted

to a study of the rural communities.

The material which he brought back, and which he has

deliberately chosen to publish with a bare minimum of editing,

throws a remarkably revealing light on the Vietnamese people’s

capacity for resistance. It shows how the individual on the spot

is standing up to the war - what he thinks about it, what

impact it has had on him, and what keeps him going. His

material and cultural background is described too.

To my mind, the most significant point to emerge from this

set of documents is the remarkable ‘deep-rootedness’ of the

men and women ofthe Vietnamese countryside and the manner

in which the American aggression can be seen to relate to them

in time and space. That aggression takes on its full historical

dimension in these interviews - a dimension which it will

probably retain, whatever else may happen. In the two-

thousand-year-old struggle of the Vietnamese people, it stands

in line with the great Chinese, Mongol and French invasions,

all of which were smashed in the end, though sometimes at a

terrible price. Whoever the invader may have been at a par-

ticular time, it has been one long, continuous fight for national

independence and freedom from oppression. Today, great

8 The Peasants of North Vietnam

heroes of the past who won victories over mighty foes - Le

Loi and Nguyen Trai, for example - are called to mind, not

only to inspire confidence and determination, hut to fill every-

one with the resolve to match the achievements of earlier times.

To remain free, to survive as a free people, to defend the

nation’s ancient and modem heritage: these are the basic

objectives. How puny, in comparison, seem the ideological

pretexts with which the Anglo-Saxons seek to slander the

victims of their expansionism.

Two of the comments reported by Gerard Chaliand are very

significant in this respect. One peasant says : ‘The Americans

are grabbing Vietnam’s resources in the South and destroying

everything we have built in the North. They’re doing it

because they want to be. masters of the world. They must be

driven out at all costs.’ And another, a Catholic living in the

district of Phat Diem: ‘The Americans are cruel, very cruel.

They are out to conquer our country so that they can rule it in

their own way. Already they are in the South, and beyond any

doubt they mean to invade us from the skies. Sooner or later

they will be beaten, though.’ Has anyone ever conveyed the

essence of a major conflict in so few and such simple words ?

Another equally fundamental point emerges from these

pages. The Pentagon wrongly imagined that escalation would

bring chaos to North Vietnam; instead,, exposure to the furnace

has considerably strengthened the nation’s institutions. The

‘patriotic war’ has completed the task of uniting the population

in a common effort. It has finally bridged the gap between the

generations, between the social classes, between the main ethnic

group and the minorities, between the Party organizations and

the workers, whatever their background, their religious faith

or their political loyalties. Events have brought the Vietnamese

people to a new level of consciousness in which nationalism,

democracy and socialism merge and interact to an even greater

degree than before.

In North Vietnam, government and Party have succeeded -

Preface by Philippe Devillers 9

more quickly, more sincerely and more effectively, it would

seem, than in any other socialist country - in identifying

Marxism with the national heritage. The political successes

which they have reaped since they placed national indepen-

dence in the forefront of their aims are ample testimony to the

truth of this statement. A nation is the product of a long

process of material, intellectual and spiritual accumulation. It

is the end-product of numberless individual and collective

contributions, of a sustained experience of human beings and

environment, of techniques painstakingly evolved and discern-

ingly applied. In short, it is the holder of a legacy which each

new generation must hand on to the next, after imprinting it

with their own labours. This is especially true of a rural com-

munity, where man is living at once in conflict and in harmony

with nature.

Why throw away the advantages of this legacy merely to

satisfy the rules of a narrow, inflexible dogmatism? By restor-

ing the concept of ‘the people, makers of history’ to its original

place of prominence, socialism is able to take over all that is

worth preserving in the country’s heritage, and to ensure the

continuity of the popular and national effort.

Readiness to inherit and reinvigorate the existing collective

institutions of the nation - in particular, the rural communities

- has made it possible for socialism to turn the country into a

genuine ‘confederation of villages’, which even the most mod-

em methods of warfare have been powerless to dismember. To

the astonishment of those who did not know Vietnam, these

thousands of living cells - enjoying a broad measure of auto-

nomy and drawing their essential nourishment from the land

and water - have held firm in spite of the terrorism to which

they have been subjected from the air. Far from disintegrating,

they have derived a new Vitality from the change in the pat-

terns of production and from the increasing democratization.

One can only hope that this new vitality will survive the war

and any future return to bureaucratic Communism. Certainly