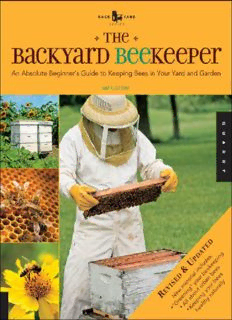

Table Of ContentThe

Backyard Beekeeper

An Absolute Beginner’s Guide to Keeping

Bees in Your Yard and Garden

Kim Flottum

Dedication

This book, the process that brought it to be, and the evolution of the information

provided here is hereby dedicated to Professor Chuck Koval, Extension

Entomologist, University of Wisconsin, Madison—who first let me in and

showed me his way of sharing information. I miss his good advice and his

humor, but not so much his liver and onions.

To Professor Eric Erickson, USDA Honey Bee Lab, Madison, Wisconsin (and

Tucson, Arizona)—who made me learn about bees, and who encouraged me to

learn, and to use what I learned to help those who could use that information.

To John Root, President (now retired), of the A. I. Root Company, Medina, Ohio

—who hired me to shepherd his magazine, Bee Culture, and who let me bring

together all that I had to take his magazine to the next generation of beekeepers.

CONTENTS

Preface

Introduction

In the Beginning

A New Concept

Chapter 1 Starting Right

First Steps: Where Will You Put Your Hive?

Bee Yards Other Than Backyards

Extreme Urban Beekeeping

Equipment: Tools of the Trade

Frame Assembly

Box Assembly

The Bees

Chapter 2 About Bees

Overview

The Queen

The Workers

Foragers

Drones

Seasonal Changes

Review and Preparation

Chapter 3 About Beekeeping

Lighting Your Smoker

Package Management

Honey Flow Time

Keeping Records

Opening a Colony

Honeycomb and Brood Combs

Integrated Pest Management

Maladies

Comb Honey and Cut-Comb Honey

Summertime Chores

Late Summer Harvest

Fall and Winter Management

Early Spring Inspections

Chapter 4 About Beeswax

Melting Beeswax

Waxing Plastic Foundation

Dealing with Cappings Wax

Making Candles

Making Cosmetic Creams

Other Beauty Benefits from Your Hive and Garden

Making Soap

Encaustic Painting

Chapter 5 Cooking with Honey

Using Honey

To Liquefy Granulated Honey

Cooking with Honey

Recipes with Honey and Your Garden Harvest

Conclusion

Glossary

Resources

Index

Photographer Credits

About the Author

Acknowledgments

Preface

Since the first edition of this book was published, a tsunami of changes have

crashed over the beekeeping world. Almost, it seems too many to number,

though I will try because it is important to delineate why this book has been

updated and revised. Though much has changed, much has stayed the same. I

have retained the sections and the information that have not changed, and that

are unlikely to change. But the ideas, techniques, and principles that are no

longer viable are no longer here.

The memory of Colony Collapse Disorder is still fresh in the minds of

beekeepers and on the pages of magazines and newspapers. It began as a

mystery, turned into a disaster, and then harnessed the power of the government,

the beekeeping industry, the media, funding agencies supported by fruit and

vegetable growers and other pollination users, cosmetic companies that use

honey bee products, and certainly the public. The threat (or supposed threat) of

the world losing this vital pollinator to an unknown disease was a wake-up call

that nearly everyone heard, and inspired many into looking at what was going

on.

In spite of all the attention, research, money, press coverage, and the

discoveries that weren’t the solution to Colony Collapse Disorder, the final

answer remained elusive. Along the way many serendipitous discoveries were

made. For instance, honey bees were increasingly being exposed to a witch’s

brew of sly new crop pesticides that were, perhaps, poorly tested and poorly

regulated before being released. In addition, climate aberrations in several parts

of the United States early on led to several of years of drought and poor

foraging. This coupled with an increasing diet of monoculture crop monotony

led to additional nutritional distress.

The bane of beekeepers worldwide was the continued presence of varroa

mites that refused to die. Beekeepers kept trying to kill them by adding more and

more toxic chemicals to their hives and not cleaning up the mess left behind. The

stress on some colonies from moving from place to place was measured by

researchers, while at the same time a nosema variant that was new (or newly

discovered) rose to stardom and unleashed its particularly nasty symptoms on

the bee population.

Some thought that maybe it was one of the viruses common to bee hives

everywhere that took advantage of all of this. Or did one of those common

viruses suddenly mutate and change the balance? Or—and I suspect this will be

found to be the answer—could it have been an opportunistic new virus (or one

not seen before in honey bees) able to capitalize on the weakness and stresses

created by all the other problems? Maybe the world knows the answer by the

time you are reading this, rendering all the questions moot and the solutions

already in motion. Maybe not.

Colony Collapse began mostly unnoticed, made lots of noise during its

second season, was at its deadliest and most noticeable the third, but by season

four made barely a whimper. And then, it was (mostly) gone. Gladly, most

beekeepers weren’t affected by Colony Collapse Disorder, nor were most bees in

the United States. Now its tune is only barely heard. At its height, however,

something like 10 percent of all the bees that died during one long cold winter

were lost to this disease alone. More were reported in Europe and elsewhere.

What was left in the wake of Colony Collapse was a much wiser beekeeping

industry. And this is why I have revised this book. During the four years Colony

Collapse Disorder was running amok I was fortunate enough to work with and

report on the results of the researchers, the primary beekeepers, the funding

agencies, the government officials, and the organizations and businesses that

devoted the time and money to bring to light the answers we now have.

We learned good lessons: keep our houses clean; keep our bees from the

harms of an agricultural world; our bees need to eat well and eat enough; and we

need to be far more diligent in monitoring the health of our colonies. As a result,

today bees are healthier, happier and more productive. Interestingly, so too are

our beekeepers.

Now, this book will fill you in on all we’ve learned. You will begin your

beekeeping adventure well armed with all this new information plus the tried and

true ways that remain. Add to this that urban and rooftop beekeeping has risen

and spread like warm honey on a hot biscuit. If you are part of this movement,

then what’s inside will be a welcome addition to your citified beekeeping

endeavors.

You are, right now, light years ahead of where beekeepers were even five

years ago. With this book, a bit of outdoor wisdom and a colony or two of honey

bees you will truly enjoy the art, the science, and the adventure of beekeeping.

You will enjoy the garden crops you harvest, the honey you and your bees

produce, and the beneficial products made from the efforts of your bees and your

work.

So again I ask, what could be sweeter? Enjoy the bees!

Kim Flottum

Backyards are good places to keep bees because they are close; urban areas support bees well

with diverse and abundant natural resources; and bees are the pollinators of choice for gardens

and landscape plants all over the neighborhood.

Description:The Backyard Beekeeper, now revised and expanded, makes the time-honored and complex tradition of beekeeping an enjoyable and accessible backyard pastime that will appeal to gardeners, crafters, and cooks everywhere. This expanded edition gives you even more information on "greening" your beekeeping