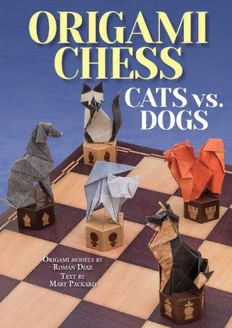

Table Of ContentORIGAMI

CHESS

CATS vs. DOGS

T M P

EXT BY ARY ACKARD

O M R D

RIGAMI ODELS BY OMÁN ÍAZ

D M N

IAGRAMS BY ARCIO OGUCHI

CONTENTS

HISTORY OF CHESS

PAPER DESIGNS

MEET THE PLAYERS

SYMBOLS, BASIC FOLDS AND BASES

THE PAWN

DACHSHUND

PERSIAN

THE ROOK

CHOW CHOW

NORWEGIAN FOREST CAT

THE KNIGHT

WHIPPET

AMERICAN SHORTHAIR

THE BISHOP

BEAGLE

SIAMESE

THE QUEEN

WEIMARANER

TURKISH ANGORA

THE KING

GERMAN SHEPHERD

DEVON REX

PEDESTAL

LET’S PLAY!

ABOUT THE ARTIST

HISTORY OF CHESS

“CHESS IS THE GYMNASIUM

OF THE MIND.”

—Blaise Pascal

The game of chess has been around for thousands of years. It thrives even today in this

fast-paced, technology-driven world. According to pollsters, chess players constitute one

of the largest communities on the planet. Worldwide, it is estimated that over 600 million

people play chess regularly. Chess develops and helps maintain focus and concentration,

and steadies the mind. For many, it serves as a tranquil retreat from the ever-present

drumbeat of too much information.

Who were the first chess players? Theories abound. There are those who believe that chess

had its origins in an Egyptian board game called senet. In this game, players moved pawns

shaped like spools and cones across a board divided into squares. The game came

equipped with four “throw sticks” that acted as dice to indicate how many spaces a player

could advance. For ancient Egyptians, the game symbolized the struggle between good

and evil and as such, a successful player was believed to be under the protection of the

gods.

Chess has been called the game of kings. The Egyptian form was no exception. A senet

game was found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun, and a depiction of the game was

discovered on the wall of the tomb of Queen Nefertari, wife of Ramses II (1304–1237

BCE).

Ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertari playing senet.

Other chess historians trace the game’s origins to chaturanga, a sixth-century strategy

game played in India. Chaturanga’s playing pieces and the 8 x 8 board they moved on

closely resembled those employed in modern-day chess. A way in which chaturanga

differed from chess, however, is that chaturanga players threw dice to advance their pieces

over the board.

In Sanscrit, chaturanga means “of four parts” and refers to the four military units that

made up an army during that time: infantry, horse cavalry, elephants, and chariots. In the

game, these army units were represented by the following playing pieces: infantry foot

soldier (pawn), horse cavalry (knight), elephant (bishop), and chariot (rook). There were

two additional playing pieces included as well—the raja (king) and king’s counsellor

(ancestor of the queen)—that would have utilized the four military units to conquer their

opponents.

The game of chaturanga also bore similarities to chess in the way the pieces moved. For

example, the king was allowed to move a single square at a time in any direction, while

the horse moved the same way a knight does today.

“CHESS IS A SEA IN WHICH A GNAT MAY DRINK AND AN ELEPHANT MAY BATHE.”

—Indian proverb

Carved relief of Ancient Indian army

Ancient bas-relief of the Persian soldiers of Persepolis, Iran

“IF A RULER DOES NOT UNDERSTAND CHESS, HOW CAN HE RULE OVER A KINGDOM?”

—Persian King Khusros

By the late seventh century, the Persian Empire had fallen to Muslim armies. Under

Muslim rule, chess pieces became abstract to conform to religious sanctions against

depicting the human image. By this time, chaturanga had spread throughout the area that

is now Iran. Persian nobles renamed the game shatranj, and quickly adopted the game for

their own amusement. Most chess scholars believe that the word “chess” is derived from

shah, the Persian word for king, and that “checkmate” comes from the phrase shah mat, or

the “the king is dead.”

Persian royalty found the game to be a useful tool for educating young princes in the art of

war. It was much safer to learn military strategy by playing chess than actually engaging

in battle.

As time went on, the game took hold among the general population. The best Persian

players became the world’s first chess celebrities. Enthusiasts devoured books written by

these chess masters to learn new openings and strategies. Some of these ancient

manuscripts survive to this day.

“CHESS IS IN ITS ESSENCE A GAME, IN ITS FORM AN ART, AND IN ITS EXECUTION A

SCIENCE.”

—Baron Tassilo

The newly expanded Muslim Empire became a multi-cultural dynasty, trading with

Europe, India, China, and Africa. Through contact with other cultures, the game of

shatranj spread northward to Algiers, and then to Spain, and by the year 1000 CE, it had

become popular throughout Europe. It is in these Western countries that chess pieces

became less abstract and figurative once more.

There can be no better example of the newly evolved style than the Lewis Chessmen set—

each figure with its own eccentrically evocative charm. Scholars have determined that the

pieces had been fashioned in Trondheim, Norway, between 1150 and 1200 CE.

No one knows how the chess pieces ended up on the Isle of Lewis—the largest of the

Hebrides Islands of Scotland—but a farmer discovered them there in 1832. As the story

goes, the farmer had been taking a walk through dunes along the beach when he spied the

tip of a stone chest poking through the sand. After digging it up, imagine his surprise

when he beheld four sets of ivory chess pieces—each with its own somewhat sad,

bewildered, or comical expression. Scholars believe that the chess sets had once been

carried on a merchant ship on its regular trade route between Norway and Ireland. What

happened to the ship and its cargo is anyone’s guess.

The Lewis Chessman set made in Norway between 1150 and 1200 CE

The game of chess can be viewed as an allegory for society during the Middle Ages.

Landowners who lived in castles are represented by the rook.

In the 1300s and 1400s the game of chess underwent changes in Europe that would make

it recognizable to modern-day chess players. Europeans gave chess pieces names that are

still used today, they devised the option of moving the pawn two squares at a time, and

adopted a new way for a pawn to capture another pawn called “en passant.” They

introduced bishops, and most notably, replaced the king’s counsellor piece with the queen.

Those who found that change too hard to accept began to refer derisively to the game as

“Mad Queen’s Chess.” Soon afterward, castling was invented to bolster the king. The new

move made the king stronger and harder to capture by moving it away from the center of

the board.

The game of chess can be viewed as an allegory for society during the Middle Ages— a

system that was based on the relationships among the nobility, the military, the church,

and the peasant class. Each playing piece represented one aspect of feudal society: the

nobility was represented by the king and queen, the military by the knight, the church by