Table Of ContentAcknowledgements

I would like to thank and acknowledge all the help I have been given over the

last two years. Two people especially have helped enormously with this book.

The first is Tony whose idea this book was and his input, particularly into the

finds chapter which was enormous, as was his help with the overall style

throughout the book.

The second is Micky who must also be mentioned. Her sketches, illustrations

and line drawings of finds are first class and provide the informal and amusing

flair that I was looking for. Also for her input into the proof reading -she

managed to correct my writing into readable English!

There are a few others like Sam at the British Museum; Nigel and Gordon

from our club who read the proofs, and corrected any slip-ups. Any mistakes that

are still there are mine completely. If you find any, please feel free to let us

know so we can correct them on the first reprint.

I would also like to acknowledge and thank the following photographers for

the use of their photographs.

The Trustees of the British Museum and the Portable Antiquities Scheme

(PAS).

Mike Hogan, who provided one of the photos of the Frome coins, and the

one of Dr. Alice Roberts and me.

Steve Minnitt, the director of Somerset Museum service who kindly

provided the Frome hoard display layout in the Taunton Museum.

Neil, a Somerset farmer, who provided a photo of himself and his cows.

Dave Crisp 2012

Editor

Greg Payne

Design Editor & Origination

Christine Jennett

Published by

Greenlight Publishing

The Publishing House, 119 Newland Street,

Witham, Essex CM8 1WF

Tel: 01376 521900

info@greenlightpublishing.co.uk

www.greenlightpublishing.co.uk

ISBN 978 1 897738 47 4 (Print)

ISBN 978 1 897738 48 1 (ePub)

ISBN 978 1 897738 4 9 8 (Mobi) eBook conversion by Vivlia Limited.

© 2012 Dave Crisp

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by

any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of

Greenlight Publishing.

Contents

Introduction

1 Brief History of Metal Detectors and Our Hobby

2 Equipment

3 Starter Detectors On Test

4 Organisations, Clubs and Dealers

5 Where To Search and Ten Ways To Gain Permission

6 The Dangers of the Farm

7 Detecting Land

8 How To Detect

9 What You Can Find – Coins

10 What You Can Find – Artefacts

11 Portable Antiquities and Treasure

12 Cleaning, Conserving and Researching Finds

13 Upgrading to a More Expensive Machine

14 Not One Hoard, But Two!

Appendices

1 The Treasure Act

2 The National Council for Metal Detecting

3 Further Reading

4 Useful Contacts

5 Grid References

Introduction

M y detecting partner Tony and I both started from scratch with no

knowledge of metal detecting whatsoever. But between us we now have

over 25 years’ of experience.

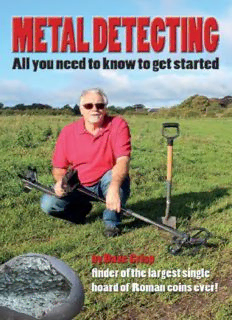

It was in July 2010, after I had found the Frome Hoard of Roman coins, that

Tony realised that there was limited information (in terms of books) for

newcomers to the hobby to buy that would tell them what they needed to know.

So he put it to me that we could put together an essential book on metal

detecting, with all the relevant information, including the Portable Antiquities

Scheme (PAS) and the1996 Treasure Act. This would also give me an

opportunity to tell my story as finder of the Frome Hoard.

Dave Crisp

Dave Crisp

We are sure that you will find in this book the knowledge that you need to

start the hobby correctly. Also covered is where to go, and how to use your

detector. You will also see a selection of finds to help on initial identification of

the objects you recover. There is a section on the 1996 Treasure Act and the

Portable Antiquities Scheme where, through your local Finds Liaison Officers

(FLOs), you can get help with the identification of finds. We have tried to make

this a light-hearted look at our hobby and how to go about it, but with a look at

the serious side of doing things correctly.

Throughout this book we have tried to emphasise the benefits of cooperation

between museums, the archaeologists involved in the Portable Antiquities

Scheme and detectorists.

We have also been very lucky to have comments and contributions from

academics such as Roger Bland (head of PAS at the British Museum); Steve

Minnet (Head of Somerset’s Museum Service), and Katie Hinds (the FLO for

Wiltshire). We are also indebted to Pippa Pearce for help on the conservation of

finds, and Sam Moor-head (Iron Age and Roman Finds Advisor at the British

Museum). Good luck and good detecting - Dave Crisp

Brief History of Metal Detectors and Our

Hobby

What is a Metal Detector?

A metal detector emits an electromagnetic field from its search coil. When a

metal object enters this field it causes a change or distortion. This is relayed to

the control box, which analyses the response and provides a sound in the

operator’s headphones and, on some models, a display on a screen. The strength

and type of the signal can also tell the detector how deep the item is, and the type

of metal it is made from. This information can also be displayed on some

detectors.

Second World War, 1942, mine detector.

One of the first detectors was built by an engineer by the name of Gerhard

Fisher. In the late 1920s he was working on radio direction finding equipment

for aircraft and found that metal ore in the ground, or metal roofs on buildings,

affected the system. From this early beginning he designed a metal detector, for

which he received a patent in 1937. These very early machines were also used

by geologists, gas and electricity companies, and the police. During the Second

World War and afterwards they also helped to clear enemy mine fields. These

early mine detectors were heavy and used a lot of power, but they were the

cutting edge of technology at the time.

Lt. Jozef Kozacki designed the first practical electronic mine detector, called

the “Mine Detector Polish Mark 1”. It was soon improved upon and mass

produced. Some 500 were issued to the British Army in time for use prior to the

Battle of El Alamein in October 1942. An example is shown here (reproduced

with permission). It looks quite familiar to a 21st century detectorist!

After the war these very early machines were used at the very start of our

hobby, although in those days you needed a partner just to carry the battery

pack! It was in the 1950s and 1960s, with the invention of the transistor, that

detectors transformed into lighter machines which used batteries that could be

fitted integrally. In America, Charles Garrett obtained a patent for a “Beat

Frequency Oscillator” type metal detector and this is when the hobby really

started up, with more and more manufacturers coming into the market. Garrett

was joined in the 1960s by other now well-known names such as White’s and

Fisher.

Shown above right is the first detector I ever purchased in the late 1960s. As

you can see, it’s just a hoop on a stick with an adapted transistor radio; but it still

works (after a fashion!). It is tuned by using the slider on the main stem. I was

assured, by the shop assistant that I would find lots of things with it! After a

couple of outings in the garden it went into the cupboard, and has seen many

more cupboards since then. I now bring it out as a curiosity when giving talks!

My first BFO metal detector from the late 1960s.

Tesoro, who started in the late 70s, became one of the early makers of a full

range of machines. One of these models was the legendary, Silver Sabre,

renowned for its ability to find small hammered coins. Tesoro, which is Spanish

for treasure, are still going and I still use my Laser B1 as a backup machine.

Great strides at that time were also being made in improving coil design,

important for depth and signal recognition. Induction Balance machines gave the

opportunity to discriminate between metals and ignore the targets you did not

want (iron). So with the ability to read the type of metal found, machines were

getting more sophisticated. Also, with further improvements in discrimination,

they were going forward in leaps and bounds.

One of the main bugbears of the early detectors was the effect on them of

minerals in the ground. Reducing the effects of this mineralisation was one of

the next big advances. However, manufacturers had to be careful in the design of

this “ground balance” as some metals give similar readings to ground minerals,

and if the facility is wrongly set some desirable objects could be lost and the

detector suffer from loss of sensitivity.

Many new designs of coils came out in the mid to late 1970s, and this led to

the development of “motion detectors”. With these, by keeping the coil moving,

the detector could discriminate and at the same time auto tune out the effects of

ground mineralisation. By the 1980s and 1990s computer technology was

incorporated into detector design, and this had a fantastic effect on the models

available.

My Minelab Explorer II detector and the Roman hoard I found with it.

So we move into the late 1990s and the 21st century. What fantastic advances

there were! Technology was advancing very quickly and giving us machines that

were never dreamt of years ago. Many of the old names - such as Garrett,

White’s, Fisher, and Tesoro - are still producing excellent machines. However,

they have been joined by others - notably Minelab that started in 1985 but now,

Description:If you have ever thought of taking up metal detecting as a hobby, or would like to give somebody a book on the subject, then this is the one to buy. Abstract: If you have ever thought of taking up metal detecting as a hobby, or would like to give somebody a book on the subject, then this is the one