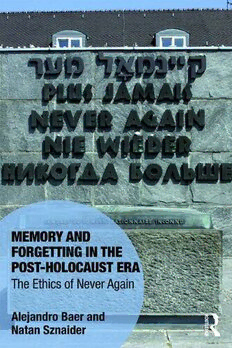

Table Of ContentMemory and Forgetting in

the Post-Holocaust Era

“This book is a courageous critique of generalizing the Holocaust into a univer-

sal frame for evil and victimhood, and making the commemoration of massive

violence a moral obligation. With sensitivity, the authors examine the costs of the

ensuing divisiveness, and propose dialogue, compromise, and the acknowledg-

ment of past suffering instead.”

– Antonius C. G. M. Robben, Utrecht University, Netherlands

T o forget after Auschwitz is considered barbaric. Baer and Sznaider question this

assumption not only in regard to the Holocaust but to other political crimes as well.

The duties of memory surrounding the Holocaust have spread around the globe

and interacted with other narratives of victimization that demand equal treatment.

Are there crimes that must be forgotten and others that should be remembered?

I n this book the authors examine the effects of a globalized Holocaust culture

on the ways in which individuals and groups understand the moral and political

signifi cance of their respective histories of extreme political violence. Do such

transnational memories facilitate or hamper the task of coming to terms with

and overcoming divisive pasts? Taking Argentina, Spain and a number of sites

in post-communist Europe as test cases, this book illustrates the transformation

from a nationally oriented ethics to a transnational one. The authors look at media,

scholarly discourse, NGOs dealing with human rights and memory, museums and

memorial sites and examine how a new generation of memory activists revisits

the past to construct a new future. Baer and Sznaider follow these attempts to

maneuver between the duties of remembrance and the benefi ts of forgetting. This,

the authors argue, is the “ethics of Never Again.”

Alejandro Baer is Associate Professor of Sociology, Stephen C. Feinstein Chair

and Director of the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University

of Minnesota, USA.

Natan Sznaider is a Full Professor of Sociology at the Academic College of Tel-

Aviv-Yaffo, Israel.

Memory Studies: Global Constellations

Series editor: Henri Lustiger-Thaler

Ramapo College of New Jersey, USA and Ecole des

Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, France

T he ‘past in the present’ has returned in the early twenty-fi rst century with a ven-

geance, and with it the expansion of categories of experience. These experiences

have largely been lost in the advance of rationalist and constructivist understand-

ings of subjectivity and their collective representations. The cultural stakes around

forgetting, ‘useful forgetting’ and remembering, locally, regionally, nationally and

globally have risen exponentially. It is therefore not unusual that ‘migrant memo-

ries’; micro-histories; personal and individual memories in their interwoven rela-

tion to cultural, political and social narratives; the mnemonic past and present of

emotions, embodiment and ritual; and fi nally, the mnemonic spatiality of geogra-

phy and territories are receiving more pronounced hearings.

T his transpires as the social sciences themselves are consciously globalizing

their knowledge bases. In addition to the above, the reconstructive logic of mem-

ory in the juggernaut of galloping informationalization is rendering it more and

more publicly accessible, and therefore part of a new global public constellation

around the coding of meaning and experience. Memory studies as an academic

fi eld of social and cultural inquiry emerges at a time when global public debate –

buttressed by the fragmentation of national narratives – has accelerated. Soci-

eties today, in late globalized conditions, are pregnant with newly unmediated

and unfrozen memories once sequestered in wide collective representations. We

welcome manuscripts that examine and analyze these profound cultural traces.

Titles in this series

The Slave Ship, Memory and the Origin of Modernity

Martyn Hudson

Forthcoming in this series

War Memory and Commemoration

Brad West

Transitional Justice and Memory in Cambodia

Peter Manning

Memory and Forgetting in

the Post-Holocaust Era

The Ethics of Never Again

Alejandro Baer and Natan Sznaider

First published 2017

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

© 2017 Alejandro Baer and Natan Sznaider

The right of Alejandro Baer and Natan Sznaider to be identifi ed as authors

of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and

78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or

utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now

known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in

any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing

from the publishers.

Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or

registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation

without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Names: Baer, Alejandro, 1970– author. | Sznaider, Natan, 1954– author.

Title: Memory and forgetting in the post-Holocaust era : the ethics of

never again / Alejandro Baer and Natan Sznaider.

Description: Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon ; New York : Routledge,

[2017] | Series: Memory studies: global constellations | Includes

bibliographical references and index.

Identifi ers: LCCN 2016025448 | ISBN 9781315616193 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Argentina—Public

opinion. | Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Spain—Public opinion. |

Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Europe, Eastern—Public opinion. |

Public opinion—Argentina. | Public opinion—Spain. | Public opinion—

Europe, Eastern. | Collective memory—Argentina. | Collective

memory—Spain. | Collective memory—Europe, Eastern. | Genocide—

Case studies. | Crimes against humanity—Case studies.

Classifi cation: LCC D804.45.A74 B34 2017 | DDC 179.7—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016025448

ISBN: 978-1-4724-4894-1 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-61619-3 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

C ontents

List of fi gures vi

Acknowledgments vii

1 The Ethics of Never Again: global constellations 1

2 Nunca Más : Argentine Nazis and J udíos del Sur 28

3 Francoism reframed: the disappeared of the Spanish Holocaust 64

4 Eastern Europe: exhuming competing pasts 105

5 Beyond Antigone and Amalek : toward a memory of hope 132

Bibliography 152

Index 168

F igures

2.1 Photographs of members of the military Junta governments

(1976–1983) at the Sitio de Memoria ESMA museum, located

in the former Escuela Superior de Mecánica de la Armada (ESMA)

secret detention center. Photo: Natan Sznaider. 32

2.2 Installation with portraits of Desaparecidos at the Espacio

Memoria y Derechos Humanos (ex-ESMA) compound, located

outside of the former Escuela Superior de Mecánica de la

Armada (ESMA) secret detention center. Photo: Natan Sznaider. 37

2.3 Memorial wall with victims’ names at the Parque de la Memoria in

Buenos Aires. Source: http://parquedelamemoria.org.ar/descargas/ 40

2.4 A “Baldosa por la Memoria” in a Buenos Aires street. Photo:

Natan Sznaider. 52

3.1 Poster of a panel discussion titled “Exemplary Transition?

From the 1978 Constitution to the recovery of historical memory”

at Complutense University in Madrid, 2010. 75

3.2 Rally in support of Judge Garzón in front of the Supreme Court

building in Madrid, 2010. Photo courtesy of Oscar Rodríguez. 76

3.3 Photography on scale one to one of the twenty-nine bodies found

in the mass grave of La Andaya (Lerma, Province of Burgos) and

portraits of its victims at Puerta del Sol square in Madrid, 2010.

The mass grave was exhumed between 2006 and 2007.

Photo courtesy of Oscar Rodríguez. 80

3.4 Picture taken on July 18, 2009, during the exhumation of a mass

grave in the village of Milagros (Province of Burgos). Pedro

Cancho, from Riaza, displays a photograph of his grandfather,

of the same name, executed by paramilitary during the

Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and allegedly buried in that

grave. Photo courtesy of Francisco Ferrándiz. 83

3.5 Logo of the Foro por la Memoria. 86

3.6 Holocaust remembrance ceremony on January 27th, 2015, at

the Spanish Senate in Madrid, presided by King Felipe VI.

Speaking at the pódium is Spain’s chief Rabbi Moshe Bendahan.

Photo courtesy of Centro Sefarad-Israel. 90

4.1 Bandera Monument in Lviv (Ukraine). Photo: Natan Sznaider. 113

5.1 Quote from Y. Yerushalmi’s book Z achor at the Centro Cultural

Haraldo Conti (ESMA memorial compound in Buenos Aires).

Photo: Natan Sznaider. 145

Acknowledgments

O ur special thanks go to Prof. Francisco Ferrándiz, the head of the research group

on” Exhumations and Politics of Memory in Contemporary Spain in Transna-

tional Perspective” at the Spanish Research Council (CSIC) in Madrid. We both

had the opportunity to be part of this research group and to profi t from Ferrándiz’s

intellectual generosity. His ideas were a constant inspiration for our book. We are

grateful to University of Minnesota graduate students Arta Ankrava and Erma

Nezirevic for their help with literature reviews and bibliographies. We also thank

Anna Brailovsky for the careful proofreading of the book manuscript.

N atan Sznaider wants to express his appreciation to his institution, the Aca-

demic College of Tel Aviv-Yaffo, for its generous support for this research proj-

ect. In addition, I would like to express my gratitude to the staff of the library,

which was always helpful in providing me with materials diffi cult to come by. I

thank Dr. Ahron Weiss for his intellectual kindness in the Ukraine in explaining

to me the pitfalls of this complicated country. At the University of Buenos Aires,

I was invited by Prof. Emilio Crenzel, Researcher at the National Council of Sci-

entifi c Research (CONICET). Prof. Crenzel provided me with many insights into

Argentinean memory politics. My thanks also go to the Parque de la Memoria

(Memory Park). I was also allowed to take some pictures, which are included in

the book. I appreciate the time I spent at the Sitio de Memoria ESMA (Memory

Site ESMA), and I am grateful to Alejandra Naftal, its director, who showed me

around there. I also visited the oral history archive of “Memoria Abierta” (Open

Memory), an alliance of fi ve Argentinian human rights organizations. My thanks

go to Susana Skura, who manages the project and took the time to talk to me about

it. I also thank Prof. Daniel Feierstein for the time he took to give me his thoughts

about the politics of memory in Argentina.

Alejandro Baer would like to express his gratitude to the Department of Soci-

ology, the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies and the College of Lib-

eral Arts at the University of Minnesota. The Research Collaborative “Reframing

Mass Violence,” funded by the Institute for Advanced Study, fostered an extraor-

dinary interdisciplinary forum to discuss with local and invited scholars the

rich array of research on memories of mass atrocities and transitional justice.

I owe great thanks to my colleague in the Sociology department Joachim Sav-

elsberg and to Barbara Frey, Director of the University of Minnesota Human

viii Acknowledgments

Rights Program, for co-convening this initiative and for being exceptional sources

of intellectual inspiration. I am indebted to Centro Sefarad-Israel in Madrid for

generously sharing materials on Holocaust remembrance initiatives in Spain,

in particular to Yessica San Román and Henar Corbi. My thanks also go to my

friends and former colleagues Pablo Francescutti (Madrid) and Bernt Schnettler

(Bayreuth) for critical feedback on portions or chapters of the book. I presented

part of the work of this book in several places, including Stony Brook University’s

“Memory in the Disciplines” project (here I thank in particular Daniela Flesler

and Adrian Pérez Melgosa), Daniel Levy and Elazar Barkan’s “History, Redress

and Cultural Memory” seminar at Columbia University and the Annual Meetings

of the American Sociological Association. Everywhere I received helpful sugges-

tions and precious critiques. I also thank Catherine Guisan, Lisa Hilbink, Bruno

Chaouat, Liliana Feierstein, Joe Eggers and Claudia Feld, as well as the students

of my course “Never Again! Memory and Politics after Genocide,” with all of

whom I have discussed many of the matters raised in this book.

1 The Ethics of Never Again

Global constellations

Angelus Novus revisited: the memory of the future

T his is a book about how people think and feel about the past and how this affects

the way they wish to shape the future. It is a book about how people interpret past

evils and try to do something to prevent them from recurring. It is a book about

moral and political knowledge and how they relate to each other. Furthermore, it

is a book about global constellations and local circumstances and the relationship

between the two. It is also a study about accountability and responsibility, particu-

larly intergenerational responsibility.

H uman rights are grounded in the dystopian consciousness of a fragile world.

The Holocaust is always in the background, and it becomes a powerful frame

for reading near and distant atrocities. Even more important is the recognition,

mediated through memories of past abuses, of the body’s universality and vul-

nerability as it becomes inscribed in popular imagination and legal doctrine.

Since 1945 ethical thought has not been able to innocently appeal to the old

world and its transcendental certainties of reason. This is especially true for

Europe and European thinking. Human rights in this respect are fi rst of all

based on memories of evil, which are then translated into the hope that such evil

will not recur. This is the meaning of the cry “Never Again” that motivated the

human rights regime especially after World War II. Hence the Universal Decla-

ration of Human Rights of 1948 states in its preamble: “whereas disregard and

contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged

the conscience of mankind” – a paradigmatic example of the ethics of “Never

again.” Never Again means never again in general but also in particular: never

again Holocaust and genocide, never again communism and other dictatorships,

never again apartheid, never again colonialism. Thus Never Again connects uni-

versal principles with particular concerns. The ethics of Never Again means

also that besides fear there lies hope.

When we think about the past, it looks like a specter is haunting our global

world, and this is the specter of a fallen angel, the angel of history painted by Paul

Klee from almost 100 years ago. This angel has become immortal through the