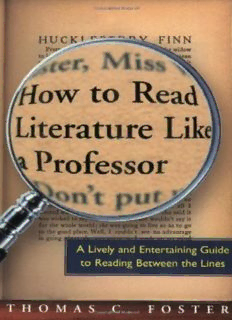

Download How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines PDF Free - Full Version

Download How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines by Thomas C. Foster in PDF format completely FREE. No registration required, no payment needed. Get instant access to this valuable resource on PDFdrive.to!

About How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines

What does it mean when a fictional hero takes a journey?. Shares a meal? Gets drenched in a sudden rain shower? Often, there is much more going on in a novel or poem than is readily visible on the surface—a symbol, maybe, that remains elusive, or an unexpected twist on a character—and there's th

Detailed Information

| Author: | Thomas C. Foster |

|---|---|

| Publication Year: | 2003 |

| Pages: | 247 |

| Language: | English |

| File Size: | 1.15 |

| Format: | |

| Price: | FREE |

Safe & Secure Download - No registration required

Why Choose PDFdrive for Your Free How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines Download?

- 100% Free: No hidden fees or subscriptions required for one book every day.

- No Registration: Immediate access is available without creating accounts for one book every day.

- Safe and Secure: Clean downloads without malware or viruses

- Multiple Formats: PDF, MOBI, Mpub,... optimized for all devices

- Educational Resource: Supporting knowledge sharing and learning

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it really free to download How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines PDF?

Yes, on https://PDFdrive.to you can download How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines by Thomas C. Foster completely free. We don't require any payment, subscription, or registration to access this PDF file. For 3 books every day.

How can I read How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines on my mobile device?

After downloading How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines PDF, you can open it with any PDF reader app on your phone or tablet. We recommend using Adobe Acrobat Reader, Apple Books, or Google Play Books for the best reading experience.

Is this the full version of How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines?

Yes, this is the complete PDF version of How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines by Thomas C. Foster. You will be able to read the entire content as in the printed version without missing any pages.

Is it legal to download How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines PDF for free?

https://PDFdrive.to provides links to free educational resources available online. We do not store any files on our servers. Please be aware of copyright laws in your country before downloading.

The materials shared are intended for research, educational, and personal use in accordance with fair use principles.