Table Of ContentComputers and the

Imagination

Visual Adventures Beyond

the Edge

Clifford A. Pickover

ALAN SUTTON

ALAN SUTTON PUBLISHING

PHOENIX MILL • FAR THRUPP • STROUD

GLOUCESTERSHIRE • GL4 2BU

First published in the United Kingdom 1991

Copyright © Clifford A. Pickover 1991

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any

form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the

publishers and copyright holder.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Pickover, Clifford A.

Computers and the imagination.

I. Title

006.6

ISBN 0 86299 999 5

To Elahe

Preface

The Buddha, the Godhead, resides quite as comfortably in the circuits of a

digital computer or the gears of a cycle transmission as he does at the top of

a mountain or in the petals of a flower; to think otherwise is to demean the

Buddha — which is to demean oneself Robert Pirsig, 1975

This book is meant to be a stimulus for the imagination - an energizing elixir for

scientific creativity. This book is also about some of the many things which

researchers do with a computer: simulating, visualizing, speculating, inventing,

and exploring. However, if a researcher’s primary investigative effort is consid

ered as the trunk of a tree, then many of this book’s topics are the offshoots,

branches, and tendrils. Some of the topics in the book may appear to be curios

ities, with little practical application or purpose. However, I have found all of

these experiments to be useful and educational, as have the many students, educa

tors, and scientists who have written to me during the last few years. It is also

important to keep in mind that throughout history, experiments, ideas and conclu

sions originating in the play of the mind have found striking and unexpected prac

tical applications. I urge you to explore all of the topics in this book with this

principle in mind.

Computers and the Imagination will appeal to the educated layperson with a

curious or artistic streak, as well as students and professionals in the sciences, par

ticularly computer science. Some of the patterns in this book can be used by

graphic artists, illustrators, and craftspeople in search of visually intriguing

designs, or by anyone fascinated by optically provocative art. The book is not

intended for mathematicians looking for a formal mathematical treatise. As my

previous book, Computers, Pattern, Chaos, and Beauty (St. Martin’s Press,

1990), the purposes of this book are:

1. to present several novel graphical ways of representing complicated data,

2. to promote and show the role of aesthetics in mathematics and to suggest how

computer graphics gives an appreciation of the complexity and beauty under

lying apparently simple processes,

3. to show the beauty, the adventure, and the potential importance of creative

thinking using computers, and

4. to encourage the use of the computer as an instrument for simulation and dis

covery.

“Lateral thinking” has been employed in the development of many of the

topics of this book. This is a term discussed by writer/philosopher Robert Pirsig

(author of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance). As he explains it,

lateral thinking is reasoning in a direction not naturally pointed to by a scientific

discipline. It is reasoning in an unexpected direction, given the actual goal one is

working toward (also see de Bono, 1975). In this book, the term “lateral

thinking” is used in an extended way, and indicates not only action motivated by

unexpected results, but also the deliberate shift of thinking in new directions to

discover what can be learned.

Imagery is at the heart of much of the work described in this book. To under

stand what is around us, we need eyes to see it. Computers with graphics capa

bility can be used to produce visual representations from myriad perspectives. In

the same spirit as Martin Gardner’s book Mathematical Circus or Theoni

Pappas’ book The Joy of Mathematics, Computers and the Imagination com

bines old and new ideas - with emphasis on the fun that the true scientific exp

lorer finds in doing, rather than in reading about the doing.

This book is a collection of some of my papers published since Computers,

Pattern, Chaos, and Beauty. With just a few exceptions, all of the described

research and computer graphics in the book are my own. However, the Introduc

tion and various one-page Interlude sections describe some unusual work by other

researchers in related fields. The Interlude sections and some of the appendices

also contain further information, images, and futuristic products to stimulate the

imagination.1

Computers and the Imagination includes topics such as scientific visualiza

tion, simulation, number theory, and computer art, and you will be urged to

explore in greater depth the ideas presented. You should be forewarned that

some of the material presented involves sophisticated concepts (e.g. “Irregularly

Oscillating Fossil Seashell”); other chapters (e.g. “The Cancer Game”) require

little mathematical knowledge in order to appreciate the subject. You are encour

aged to pick and chose from the smorgasbord of topics. Many of the articles are

brief and give you just a flavor of an application or method. Often, additional

information can be found in the referenced publications. In order to encourage

your involvement, computational hints and recipes for producing some of the com

puter-drawn figures are provided. For many of you, seeing pseudocode will

clarify concepts in ways mere words cannot.

' Note: Although all of the products listed in this book provide a stimulus for the imagination, they are

listed for illustrative purposes only. The author does not endorse any particular software or

product, nor does he accept responsibility for the selection of any products by the reader. The opin

ions expressed in this book are the author’s and do not represent the opinions of any organization or

company.

The book is organized into nine main sections:

1. Simulation. In the quest for understanding natural phenomena, we turn to

several simple computer simulations. These experiments are the easiest in the

book for students to implement and explore, and include butterfly curves and

cancer growth simulations.

2. Exploration. In this section, the interesting weave of “mathematical fabric”

is explored. Topics include the Lute of Pythagoras, earthworm algebra,

number theory, super-large numbers, and the elusive cakemorphic integers.

3. Visualization. Computer graphics has become indispensable in countless

areas of human activity. Presented here are experiments using graphics in

biology, mathematics, and art. Topics include pain-inducing patterns, sea-

shells, and voltage sculptures.

4. Speculation. In this section are several speculative survey articles. Topics

include “Who are the ten most influential scientists in history?” and “What is

the social and political impact of a soda-can-sized supercomputer?”

5. Invention. This section describes several inventions. Topics include anti-dys

lexic fonts and speech synthesis grenades.

6. Imagination. Discussed here are computer-generated poetry and stories.

7. Fiction. Presented in this section are a few short stories dealing with com

puters and scientific experiments.

8. Exercises for the Mind and Eye. This section presents imaginative unsolved

puzzles and curiosities. There are also serious experiments for future

research. Described in this section are Grasshopper sequences and the

Amazon skull game.

9. Computers in the Arts and Sciences. This last section treats you to a list of

unusual resources on the subject of computers in science and art. Listed are

individuals and companies distributing computer art, music, and films, and

also some references to unusual literature.

In deciding how to organize the material within these sections of Computers

and the Imagination, I considered a number of divisions - computer- and non-

computer-generated forms, science and art, nature and mathematics. However,

the lines between these categories become indistinct or artificial, and I have there

fore arranged the topics randomly within each section to retain the playful spirit

of the book, and to give you unexpected pleasures. Throughout the book, there

are suggested exercises for future experiments and thought, and directed reading

lists. Some information is repeated so that each chapter contains sufficient back

ground information, and you may therefore skip sections if desired. Smaller type

fonts, as well as the symbols [[ and ]], are used to delimit material which you can

skip during a casual reading, and a glossary is provided for some of the technical

terms used in the book.

At the beginning of many chapters of Computers and the Imagination are

large computer-generated “sculptures” constructed with tiny black dots. These

images are actually created from simple mathematical formulas, and each con

tains precisely one-million dots. Background information, as well as algorithmic

recipes for these sculptures, can be found in “Million-Point Sculptures” on

page 285. Other frontispiece figures include grotesque Digital Monsters which

are discussed in “Descriptions of Color Plates and Frontispieces” on page 393.2

The basic philosophy of this book is that creative thinking and computing are

learned by experimenting. I conclude this preface with a quote from Morris Klein

0Scientific American, March 1955) that encompasses the general theme of this

book:

The creative act owes little to logic or reason. In their accounts of the cir

cumstances under which big ideas occurred to them, mathematicians have

often mentioned that the inspiration had no relation to the work they hap

pened to be doing. Sometimes it came while they were travelling, shaving, or

thinking about other matters. The creative process cannot be summoned at

will or even cajoled by sacrificial offering. Indeed it seems to occur most

readily when the mind is relaxed and the imagination roaming freely.

For Further Reading

1. De Bono, E. (1970) Lateral Thinking: Creativity Step by Step. Harper and

Row: New York.

2. Gardner, M. (1979) Mathematical Circus. Penguin: England. (A collection

of interesting puzzles, paradoxes, and games.)

3. Gardner, M. (1978) Aha! Insight. Freeman: New York. (A collection of

puzzles which encourages creative leaps of thought, leading to solutions of

seemingly impossible problems.)

4. Pappas, T. (1989) The Joy of Mathematics. Wide World Publishing: Cali

fornia. (A collection of mathematical puzzles and concepts for the layperson.)

5. Pickover, C. (1990) Computers, Pattern, Chaos, and Beauty. St. Martin’s

Press: New York.

6. Pirsig, R. (1975) Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Bantam: New

York. (A philosophical story dealing with humans and technology.)

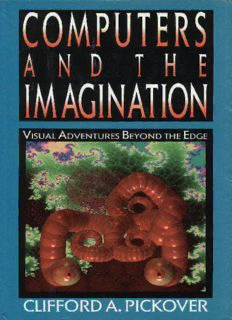

- Book cover. The cover of this book shows an image of a creature which the author rendered using an

IBM RISC System/6000 computer. Many aspects of the figure, including color, lighting, and

shading, are controlled by a computer program. The creature’s body was created using formulas

which produce three oscillating spiral shapes. The intricate background and diffuse collection of

tiny spheres toward the back of the figure were also generated by simple formulas. Information on

other color plates can be found in “Descriptions of Color Plates and Frontispieces” on page 393.

'Thinking is more interesting than knowing,

but less interesting than looking

Wolfgang von Goethe

Description:Recent books by James Gleick, Martin Gardner, and Benoit Mandelbrot have made the topics of Chaos theory and fractals an integral part of the terrain for the computer literate. They have shown the revolutionizing role of the visualization of complex mathematical data. Computers and the Imagination p