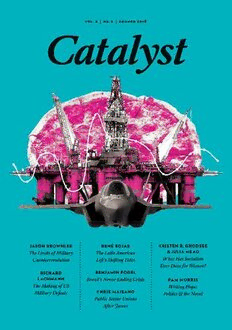

Table Of ContentCatalyst

volume 2 issue 2 summer 2018

3

Editorial

7 101

rené rojas kristen r. ghodsee

The Latin American & julia mead

Left’s Shifting Tides What Has Socialism Ever

Done for Women?

73

benjamin fogel 135

Brazil’s Never- chris maisano

Ending Crisis Public Sector Unions

After Janus

debate

151 183

jason brownlee richard lachmann

The Limits of Military The Making of US

Counterrevolution Military Defeats

review

205

pam morris

Writing Hope: Politics

& the Novel

CONTRUBUTORS

jason brownlee chris maisano

is a professor in the department is a contributing editor at Jacobin and

of government at the University of a union staffer in New York. He is on

Texas – Austin. He is the author the national political committee of the

of Democracy Prevention: The Politics Democratic Socialists of America.

of the U.S.-Egyptian lliance (Cambridge,

2012) and is completing a book julia mead

manuscript on US military is a history PhD student at the

interventions after the Cold War. University of Chicago. Her writing

has appeared in the Nation, New

benjamin fogel York Magazine, and elsewhere.

is doing a PhD on the history of

Brazilian anti-corruption politics pam morris

at NYU, and is a contributing editor is an independent scholar, previously

with Jacobin and Africa is a Country. a professor of modern critical studies

and head of the Research Centre

kristen r. ghodsee for Literature and Cultural History

teaches Russian and East European at Liverpool John Mores University.

Studies at the University of Her books include Dickens’s Class

Pennsylvania. Her research focuses Consciousness: A Marginal View

on gender, socialism, and post- (Macmillan, 1991), Realism (Routledge,

socialism in Eastern Europe. 2003) and Jane Austen, Virginia

Woolf and Worldly Realism (Edinburgh

richard lachmann

University Press, 2018).

teaches sociology at the University

at Albany, State University of rené rojas

New York. His book, First Class teaches sociology and political science

Passengers on a Sinking Ship: Elite at Hobart and William Smith Colleges.

Politics and the Decline of Great Powers, His research is on neoliberal develop-

is forthcoming from Verso. ment and politics in Latin America,

where he spent years as an activist.

Editorial

T he rise and fall of the Left dominates this issue of Catalyst.

Or to be more precise, the Left in the global periphery. In the

advanced capitalist world, the last few years have seen a tremendous

turn against the political establishment, and even a revitalization of

socialist politics. Jeremy Corbyn continues to be the most popular

politician in Britain, while Bernie Sanders’s political influence is not

only formidable, but gathering momentum.

It seems only yesterday that similar changes were underway in Latin

America. After two decades of brutal neoliberal austerity, left-wing

governments came to power across the region — in Argentina, Bolivia,

Brazil, Ecuador, and Venezuela, among others. This was the onset of the

Pink Tide, a resuscitation of radical politics and, in some cases, even

of a socialist vision. But in contrast to the events in the North, the left

turn in South America seems to have run its course.

In our lead essay, René Rojas offers a sweeping analysis of this quite

dramatic reversal of fortune. Rojas echoes the observation made by Pink

Tide critics, that, despite their rhetoric, the regimes failed to break out

3

CATALYST • VOL 2 • №2

of the neoliberbal orthodoxy they had inherited. He insists, however,

that this failure was not due to insufficient will, but to political capacity.

Whereas the classical Latin American left in the 1960s and ‘70s acquired

power in an era of rapid industrialization and growth of the working

class, the Pink Tide formed amid a period of deindustrialization and

labor-market informalization. The Left in Allende’s time could rely on a

social base located in core economic sectors. The more recent left was

based in shantytowns and a precariat which, while radical and mobi-

lized, could not give it the leverage needed to push through reforms

against bourgeois opposition.

One of the symptoms of the Pink Tide’s weakness was a slide into

clientelism and patronage politics. Nowhere has this been more evi-

dent than in the decline of the Workers’ Party (pt) in Brazil. Once held

as the beacon of the regional left resurgence, the party is now reeling

under the blows of a massive corruption scandal and the conviction

of its leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Benjamin Fogel provides a lucid

analysis of the forces behind the scandals. He shows in some detail

how the constraints that Rojas describes in his essay, both political and

economic, have operated in the Brazilian context. But just as impor-

tantly, he criticizes the pt for failing to devise a strategy to overcome

them, succumbing instead to the tawdry machinations of the political

class. Here, as in other episodes of left accommodation, acquiring and

holding office has rapidly overtaken the vision that originally inspired

the movement.

The despair that so many Brazilians feel today is what the Palestinians

have lived with for decades. As Bashir Abu-Manneh shows in his study

of Palestinian literature, the experience of defeat and dispossession in

1948 had profound consequences for the people, not just politically but

also culturally. He argues that the trauma of the nakba triggered not just

a search for meaning, but also for a literary form in which to express it,

a turn away from realism toward modernist techniques of representa-

tion. In a sensitive review of Abu-Manneh’s book, Pam Morris notes

4

EDITORIAL

that while György Lukács criticized modernist literature as a retreat

from reality, a turn inward, Abu-Manneh sees it as a struggle to retain

a sense of hope amid an unending political retreat.

It is the recovery of lessons from a submerged past that motivates

Kristen Ghodsee and Julia Mead’s essay. For much of the Western left

today, Eastern European state-socialist regimes comprise episodes

best forgotten — experiments in social control that only discredited

attempts to build a more humane future. But as Ghodsee and Mead

point out, there are still some positive lessons to be gleaned from

them, especially with regard to gender relations. Chief among these

is the importance of economic redistribution — precisely what makes

establishment liberals nervous today.

The issue is rounded out by a clutch of articles on the capitalist core.

Chris Maisano offers a short note on the historic Supreme Court ruling

which eliminated agency fees for public sector unions. As Maisano

observes, the case was intended to further weaken the labor movement

by striking it where it still has some power. But the story is anything

but over — just weeks before the ruling was made, several states were

rocked by the largest strike wave in recent years, all in the public sector.

Even as unions reel under its blow, the strikes show a way forward.

Finally, we feature a debate between Jason Brownlee and Richard

Lachmann on US imperialism. Brownlee agrees with Lachmann’s argu-

ment, in his essay from Catalyst 1, no. 3, that the military has proven to

be a weak instrument for American global expansion since Vietnam,

but suggests that Lachmann has misdiagnosed its causes. Lachmann

offers a defense of his views, while agreeing that there is much to

Brownlee’s argument.

The question of US power will occupy a prominent place in forth-

coming issues of Catalyst.

5

CATALYST • VOL 2 • №2

Viewed by many as the most promising

development for the global left in decades, the

Pink Tide is in retreat. To understand

its decline, this essay compares its rise and

achievements to the rise of the region’s

classical left, which emerged following

the Cuban Revolution. Whereas the classical

left’s accomplishments were rooted in the

structural leverage of industrial labor,

the Pink Tide has been based on movements

of informal workers and precarious

communities. The Pink Tide built its base from

a social structure that had been transformed

by two decades of deindustrialization

and industrial fragmentation. This had two

critical implications — it gave newly

elected governments far less leverage against

ruling classes than the earlier left, and it

also inclined them toward a top-down,

clientelistic governance model, which turned

out to be self-limiting. In the end, Pink Tide

regimes were undone by their own constituents,

whereas the classical left was toppled

by the elites that it attempted to dislodge.

6

THE LATIN AMERICAN

LEFT’S SHIFTING TIDES

rené rojas

T he new millennium unleashed a wave of popular rebellions

in Latin America, which propelled a number of left govern-

ments into power. These governments came to be known as the Pink

Tide, and while they have not pursued full-blown “red” policies, they

received enthusiastic support from radical quarters, including from

some of our leading thinkers. Noam Chomsky, for instance, praised the

achievements of the new reformers in the areas of democracy, sover-

eign development, and popular welfare.1 The ability of these countries

to soften neoliberalism’s worst effects, empower popular sectors, and

stand up to US domination mark a welcome rebound from the prior

“lost decades” of market fundamentalism and social exclusion. In the

global context, the Pink Tide contrasts starkly with full-blown neolib-

eral continuity in the capitalist core and the discouraging outcomes of

the Arab Spring in the Middle East.

Yet the tide is receding, and unlike daily coastal ebbs, the decline of

1 See also Tariq Ali’s enthusiastic praise of the Pink Tide in Tariq Ali and David Bar-

samian. Pirates of the Caribbean: Axis of hope (London: Verso, 2006).

7

CATALYST • VOL 2 • №2

the region’s left is a longer-term retreat of reform governments. After

Hugo Chávez came to power in 1999 as an outsider populist-nationalist,

Lula, the historic leader of the Workers' Party, was elected president of

Brazil in 2002, followed by Nestor Kirchner in Argentina in 2003, Evo

Morales in Bolivia a year and a half later, and Rafael Correa in Ecuador

one year after that. They and their successors enjoyed impressive runs.

But beginning in 2015, key losses initiated a reversal of the Left’s for-

tunes. That year, elections took down reform Peronism. Then followed

a “constitutional coup” that toppled Dilma Roussef in Brazil. Rafael

Correa’s coalition in Ecuador is crumbling after his reform candidate

just eked out a win. Although Morales’s hold on power remains firm,

when Nicolás Maduro goes in Venezuela, bringing down with him

what remains of the Bolivarian Revolution’s accomplishments, the

cycle will be complete.2

How should we evaluate the Pink Tide? What is its true record

of achievements and failures? What undercut its promise and

AS reversed its ascent? Interestingly, most assessments, from friends

OJ

R and foes alike, point to avoidable mistakes made by politicians

and their parties. From the Right, analysts divide Latin American

reformers into good and bad lefts, arguing, unsurprisingly, that Pink

Tide shortcomings emanate from their original populist sin. There,

while natural rents could buy popular allegiance, such patronage

corroded stable republican institutions, irreparably polarized political

and civil society, and inevitably led to fiscal disaster. Others from

the Left, mostly radicals, point not to its demagogic overreach, but

to the reformers’ docility and acquiescence to elite power. Here,

reformers are scolded for not going far enough; indeed, even the

“wrong” strategies scorned by conservatives confined themselves

2 As in all stylized periodizations, there will be exceptions, which are no less import-

ant by virtue of being outliers. The landslide election of national-populist AMLO in

Mexico will take on special meaning if the former PRI and PRD politician manages to

adopt a genuine reform program despite his dubious pedigree. There are also prom-

ising new radical lefts, such as the Broad Front in Chile, that must consolidate before

they can vie for power.

8