'Yo!' and 'Lo!': The Pragmatic Topography of the Space of Reasons PDF

Preview 'Yo!' and 'Lo!': The Pragmatic Topography of the Space of Reasons

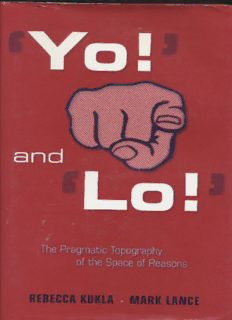

The Pragmatic Topography of the Space of Reasons MARK LAN Yo!' and 'Lo!' The Pragmatic Topography of the Space of Reasons ebecca Kukla ark Lance RVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS bridge, Massachusetts don, England To Wilfrid Sellars Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America lo, a rabbit!' —W V O. Quine Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kukla, Rebecca, 1969— Yo! and Lo! : the pragmatic topography of the space of reasons / Yo) Word up! Rebecca Kukla, Mark Lance. —Dead Prez p. cm. includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-674-03147-0 (alk. paper) You tal kin' to me? I, Pragmatics. 2. Speech acts (Linguistics) 3. Language and languages— —Travis Bickle Philosophy. L Lance, Mark Norris. 11. Title. P99.4.P72K85 2008 410---dc22 (cid:9) 2008011161 viii (cid:9) Contents 5.2 Four Ways of Telling Someone What to Do 105 5.3 Two Alternative Accounts (cid:9) 113 Acknowledgments 5.4 Reasons, Claims, and Addresses (cid:9) 122 5.5 Coda: Categorical Imperatives(cid:9) 128 6 Vocatives, Acknowledgments, and the Pragmatics (cid:9) of Recognition 134 6.1 Two Kinds of Recognitives (cid:9) 137 6.2 Vocatives (cid:9) 138 This book is the direct result of almost exactly five years of intensive 6.3 Acknowledgments (cid:9) 145 joint philosophical work. Prior to that, each of us had thought hard (cid:9) about certain themes in this book for many years. Our shared discovery 7 The Essential Second Person 153 of the possibilities for synthesizing the ideas that we had been pursuing 7.1 Concrete Habitation of the Space of Reasons (cid:9) 155 separately—occasioned by a graduate seminar at Georgetown Univer- 7.2 Second-Person Speech (cid:9) 160 sity—dramatically transformed each of our thinking and created some- 7.3 Tellings, Holdings, and Transcendental Vocatives (cid:9) 163 thing wholly new It would be hard to overstate the intellectual excite- 7.4 Speech as Communication and as Calling(cid:9) 171 ment of those early conversations during which this book was born. Finding someone who not only understands what you are up to, but (cid:9) 8 Sharing a World 179 whose work immediately opens up new possibilities for the formulation and development of your own, and with whom you can explore, chal- 8.1 1nterpellation and Induction into Normative Space (cid:9) 180 lenge, deepen, and make that work more precise, all in a context that is 8.2 Membership in the Discursive Community (cid:9) 190 intellectually smooth, is a rare and treasured moment in a life. 8.3 How Many Discursive Communities Are There? 195 Since those initial meetings, the work on this book has been utterly 8.4 Sharing a World and Learning to See 205 collaborative. We talked through each major idea and argumentative 8.5 On the Equiprimordiality and Entanglement of move in advance of any writing. Though initial drafts of chapters were Ye and TO 210 often undertaken by one of us, subsequent drafts always went to the 8.6 Fugue 212 other, and later drafts were written and rewritten line by line as we sat together in front of the monitor. There is no chance that any part of this Appendix: Toward a Formal Pragmatics of Normative (cid:9) book could have existed in anything like its current form without that Statuses (with Greg Restall) 217 collaboration. Not only could neither of us have found our way down (cid:9) this road alone, but we are certain that neither of us could have done so Index 235 with any other companion. But of course if we had talked only to each other along the way we would have descended into madness. We have been supported and joined by a magnificent intellectual community. Two people deserve spe- cial mention for their essential, engaged, and generous help: Richard Manning organized and participated in a day-long "jam session" on the book at Georgetown University when it was very much a work in prog- ix x (cid:9) Acknowledgments (cid:9) Acknowledgments (cid:9) xi ress, and the conversations we had that day altered and enriched the Rebecca as a visitor for three years that the opportunity for this collab- book. At least as important, he gave us detailed, line-by-line comments oration came to be. Carleton University awarded Rebecca a Marston on an early draft, and as always proved himself both a penetrating reader LaFrance Research Award, which gave her an entire paid year of release and a maddeningly reliable bullshit detector. We overhauled much of from teaching to finish this book. Several trips between Ottawa, Wash- Chapters 1 and 2, in particular, in response to his comments. Margaret ington, and Tampa for the purpose of writing together were funded Little has been a constant sounding-hoard for ideas, testing our intu- by Rebecca's grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research itions, challenging underlying assumptions, directing us to relevant lit- Council of Canada. Mark was able to work with Greg Restall in Mel- erature in moral philosophy, pushing us to formulate points more clearly, bourne thanks to a grant from the University of Melbourne visiting and suggesting everything from clarifying examples to more perspicu- scholars program. Camille Smith did a superb job of editing the entire ous formulations of views. Indeed, much of Maggie's own work on deon- manuscript, and Phoebe Kosman and Lindsay Waters of Harvard Uni- tic pluralism and intimacy has tendrils that have penetrated our thought. versity Press helped us throughout the editing and publishing process. It is hard to imagine more supportive and stimulating colleagues and Finally, as is standard but no less genuine for that, we thank our wise friends than Maggie and Richard. spouses, Richard Manning (same person, different guise) and Amy Hub- Sincere thanks go to our coauthor on the Appendix, Greg Restall, who bard. They put up with long trips, extra parenting duties, late nights, was kind enough to arrange a grant for Mark to visit Melbourne for two early mornings, grouchiness when the issues were particularly recalci- months. During that time Mark and Greg worked out the basics of the trant, and excessive giddiness when the solutions came quickly They formal Appendix and discussed in detail how a formal perspective could rolled their eyes only internally when we lapsed periodically into a illuminate and refine the philosophical meat of the book. The three of us cryptic dialect comprehensible only to the two of us. Our children, Eli developed later versions of the Appendix together, and we fully expect Kukla-Manning and Emma Lance, inspired and forbore. Throughout, the tripartite collaboration to continue. much slack was taken up. Many people have helped us with their suggestions, objections, skep- ticism, and sympathy. An undoubtedly partial list includes William Blattner, Taylor Carman, Alan Gibbard, Mitch Green, John Haugeland, Elisa Hurley, Paul Hurley, Andre Kukla, Coleen Macnamara, Chauncey Maher, James Mattingly, John McDowell, Niklas Moller, Mark Okrent, Terry Pinkard, Alex Pruss, Joseph Rouse, Charles Taylor, Michael Wil- liams, and audiences at Queens University, Georgetown University, the University of Virginia, the International Association for Phenomeno- logical Studies, the Johns Hopkins University, the University of Cape Town, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Melbourne, and the University of Cincinnati. Special thanks go to Colleen Fulton, the world's greatest R.A., who gave us invaluable com- ments on the entire manuscript, and to Philip Kremer and Juliet Floyd, who prepared wonderful critical responses to our work for the work- shop that Richard organized at Georgetown. 111 We have been exceptionally well supported by various institutions. It is only because the Georgetown University philosophy department, through the efforts of its superlative chair, Wayne Davis, welcomed 1 Pragmatism, Prag matics, and Discourse: Mapping the Terrain In the beginning was the Word!" Here Fm stuck already! Who helps me go further? The spirit helps me All at once I see the answer. And confidently write: "In the beginning was the Act!" —Goethe In this book we examine how speech acts alter and are enabled by the normative structure of our concretely incarnated social world. In other words, we examine language through the lens of pragmatism, in the metaphysical sense that takes the phenomenon of language to be, in the first instance, a concrete, embodied social practice whose purpose is meaningful communication. We argue that, by beginning with our anal- ysis of the normative functioning of speech acts, we can clarify the struc- ture (and sometimes make progress toward a solution) of some key is- sues in metaphysics and epistemology, including the role of perception in grounding empirical knowledge, how we manage to engage in inter- subjective inquiry with objective import, the nature of moral reasons, and the capacity of subjects to be responsive and responsible to norms. Using an image that would grip the imaginations of at least three generations of philosophers, Wilfrid Sellars placed us—that is, us beings capable of language, thought, intention, meaning, and normative ac- countability—within a 'space of reasons', set over and against a space of mere causes. For some close followers of Sellars, most emblemati- cally Robert Brandom, this space is first and foremost a space of inferen- tial relations between declarative propositions.' John McDowell's post- . 1. Robert Brandom, Making it Explicit: Reasoning, Representing, and Discursive Commitment (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1994). 2 (cid:9) ` Y o?' and 'Lot' Pragmatism, Pragmatics, and Discourse (cid:9) 3 Sellarsian space of reasons is a provocatively richer and perhaps more to use for making claims about, and upon, the world and one another. A ambiguous one. The relationship between the deliverances of experi- crucial upshot of our analysis will be that meaningful speech acts are ence and the space of reasons is complex rather than merely opposi- fundamentally indexed to particular agents with particular stances, sub- tional for McDowell.2 But none of the authors who have developed and stantial relationships to other particular agents, and locations within philosophically mined the metaphor of the space of reasons have taken concrete social normative space that are ineliminably first- and second- particularly seriously what its overall pragmatic structure may be, nor personally owned by this or that living, embodied subject who has a par- have they given detailed attention to how different normative pragmatic ticular point of view and is capable of making and being bound by relations might importantly inflect and constitute this space. We aim to claims. rectify this absence through an exploration of what we call the "prag- Our central conceptual tool, introduced later in this chapter, is a matic topography" of the space of reasons. We develop a framework for typology of speech acts—or, more precisely, of normative dimensions of thinking about the normative pragmatic structure of discursive speech speech acts—that is orthogonal to the usual systems of pragmatic cate- acts, guided by the presumption that the pragmatic structure of the gorization (by performative force, etc.). We believe this typology has space of reasons can be no less rich than that of discourse. surprisingly large philosophical payoffs. There is nothing uniquely priv- Like any beginning, this beginning in the concrete normative struc- ileged or architectonic about our typology; there are plenty of legitimate ture of discourse embodies two commitments: that the starting point ex- ways of dividing up speech acts along pragmatic lines, and surely differ- ists, and that it is a good place to start. Existentially, we are committed to ent ways have different benefits and clarify different philosophical is- the claim that language has systematic normative effects and functions, sues. What we claim on behalf of our typology is, first, that the mere fact that these essentially depend on the concrete ways in which speakers are that it is substantially different from the categorization systems used by enmeshed in social communities and environments, and that discursive linguists and other philosophers of language serves to de-naturalize the performances systematically transform the normative statuses of speak- more traditional systems, and to broaden our philosophical imagination ers and of those spoken to. Prescriptively, we are committed to the prin- and vision, and, second, that its use can make some seemingly impene- ciple that this dimension of language and discursive practice forms an trable philosophical questions appear quite straightforward. explanatorily useful entering point for thinking about larger questions concerning our contact with the empirical world, with normative force, 1.1 Varieties of Pragmatism and with one another. We can afford to be quite liberal about what counts as a speech act; for There are two large camps of philosophers who fly the banner of prag- our purposes, a speech act is a communicative act that functions norma- matism, plus an additional camp of those who do not necessarily iden- tively within a structured system of communication. We don't much tify as 'pragmatists' but who study the pragmatics of language. Although care about nailing down the boundaries of the notion, but it is clear that we think that we are true to (what ought to he) the spirit of pragmatism, we can count many gestures, written signs, facial expressions, and more and although we are centrally concerned with the pragmatics of lan- as speech acts. Such acts may or may not have a determinate syntactic or guage, we depart substantially from all three camps. First, there are phi- semantic structure, but it is an integral consequence of our account that losophers who find their roots in the classic American Pragmatists such they have a rich and determinate pragmatic, communicative structure— as Dewey James, and Pierce, and often also in the early work of Heideg- one that is of the right sort to let them participate in a discursive system ger and his French successors such as Pierre Bourdieu and Maurice that lends itself to semantic and syntactic analysis, and of the right sort Merleau-Ponty.3 This group has productively focused on embodied prac- tice as the ineliminable site of human meaning, and has worked to shift 2. See in particularjohn McDowell, Mind and World (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. 1994), and McDowell, "Having the World in View: Kant, Sellars, and Intentionality,' 3. Typical recent examples include Shannon Sullivan, Living Across and Through Skins Journal of Philosophy 65 (1998): 431-450. SellarsIs own view of the relation between the spaces (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), and Samuel Todes, Body and World (Cam- is hard to pin down. bridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2001). 4 (cid:9) 'Yol' and `Lo!' Pragmatism, Pragmatics, and Discourse(cid:9) 5 epistemological attention to local and contextual epistemic practices, many—though not all—philosophers who work on formal pragmatics and away from the quest for transcendent truths, universal principles, share with both camps of pragmatism an explanatory privileging of the and absolute certainty. pragmatic dimensions of language, this last group departs from the first Second, there is what we might call "Pittsburgh School Pragmatism," two in generally treating-syntax, semantics, and pragmatics as indepen- represented paradigmatically by Wilfrid Sellars, John McDowell, Rich- dently analyzable, and taking mental meanings and representations as ard Rorty, Robert &random, Donald Davidson, and John Haugeland, 4 given independently and in advance of performative utterances.' and characterized by anti-reductionism and anti-representationalism in We share some methodological commitments with each of the three the philosophy of mind and epistemology with roots in Wittgenstein. camps we have just described. The priority of the pragmatic in the order These philosophers are committed to the principle that the best place of explanation is important to us; we shall return to this point in detail from which to begin thinking about intentional phenomena such as below. We believe that meaning and normativity are phenomena that are meaningful speech acts and contentful mental states is with our practi- ineliminably grounded in socially located human bodies, that reduction- cal interactions with the world and with others, and their normative ism and classical representationalism are bankrupt projects in philoso- structure. For example, in the preface to Making It Explicit, Brandom phy of mind and epistemology, and that there is an important place for writes: formal theories in attempts to understand the pragmatic structure of language. On the other hand, we see each of these three orientations as The explanatory strategy pursued here is to begin with an account of having serious limitations. social practices, identify the particular structure they must exhibit in The first camp has tended to privilege embodied practice over concep- order to qualify as specifically linguistic practices, and then consider what different sorts of semantic contents those practices can confer on tual discourse and thought, seeing the former as more fundamental and states, performances, and expressions caught up in them in suitable more interesting than the latter!' To do so is to assume that discourse ways.) and thought are not themselves embodied practices,9 and it is also, we think, to undervalue the philosophical centrality of language and dis- Finally, there are philosophers of language such as William Alston and cursive judgment in making possible our status as epistemic and moral John Searle, who work in close collaboration with linguists and focus on subjects and our receptivity to the claims and character of the empirical speech act theory, looking backwards to Austin and Grice.t These phi- world. losophers seek to develop a formal pragmatics that can sit alongside for- Our points of convergence with and divergence from the second and mal theories of semantics and of syntax. In the imperfect tripartite divi- third camps—the Pittsburgh School Pragmatists and the theorists of sion of language into syntax, semantics, and pragmatics, there is rough formal pragmatics—deserve some detailed discussion right up front. agreement that syntax is the study of well-formedness, or grammatical- Sellars, Brandom, Davidson, and other anti-representationalist are ity, semantics is the study of meaning, and pragmatics is the study of the methodologically committed to a particular explanatory starting point way bits of language are used in the performance of speech acts. While 7. For instance, Kent Bach writes: "Different types of speech acts (statements, requests, 4. For example see Wilfrid Sellars, Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind (Cambridge, apologies, etc.) may be distinguished by the type of propositional attitude (belief, desire, regret, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997); Richard Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature etc.) being expressed by the speaker . Many philosophers would at least concede that mental (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), Donald Davidson, Subjective, Intersubjective, Ob- content is a more fundamental notion than linguistic meaning, and perhaps even that seman- jective (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001); McDowell, Mind and World; and Brandom, tics reduces to propositional attitude psychology" (online..sfsicedut—hbach/grice.htm, accessed Making It Explicit. 10/10/07). 5. Brandom, Making It Explicit, xiii. 8, Classic examples include Hubert Dreyfus, What Computers Still Can't Do: A Critique of 15. See for example William Alston, Illocutionary. Acts and Sentence Meaning (Ithaca: Cornell Artificial Reason (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1992), and Todes, Body and World. University Press, 2000); John Searle, Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language 9. Joseph Rouse, in How Scientific Practices Matter: Explaining Philosophical Naturalism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969); and Wayne Davis, Meaning, Expression, and (cid:127) (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), does an excellent job of systematically defending Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2003). a picture of discourse as continuous with, rather than derivative upon, embodied practice. 6 (cid:9) Tol' and To!' Pragmatism, Pragmatics, and Discourse(cid:9) 7 in philosophy of mind and language, namely an account of the role that only insofar as they are properly situated within a body of discursive discursively formed encounters with the world and with one another practices that is their constitutive precondition. Despite our agnosticism play in constituting the normative statuses of participants in a discursive about the reducibility of semantics to pragmatics, our acceptance of the community—an account of the acts that form what Brandom (attribut- pragmatists' order of explanation puts us at odds with most philoso- ing the thought, if not the phrase, to Sellars) calls the "game of giving phers working on speech act theory and formal pragmatics. Indeed, for and asking for reasons." It is attention to the social practices of dis- typical theorists of pragmatics, things go almost exactly the other way course, according to this approach, that is our best way into thinking around. Mental states, particularly intentions, are typically taken for about how language manages to be suitably responsive to the world, and granted for the purposes of linguistic theory. Of course, philosophers hence how this responsiveness is codified in a semantics and a syntax. such as Searle have accounts of mind, but their theories of mental repre- Furthermore, Sellars tenaciously argued—following Hegel and Wittgen- sentation cast it as independent of, and in important senses prior to, lan- stein—that intentional mental states are best understood as derivative guage. The job of the theorist, on this view, is to characterize the range and dependent upon meaningful discursive practice, and his philosoph- of ways a person can then intentionally put a sentence—usually seen as ical descendents have championed this commitment. So on this picture, having an unproblematic syntax—to use. Accordingly, such philoso- philosophical explanation moves from discursive use, to content and phers follow the linguists' odd practice of treating categories of speech grammar, to mind. acts that mark pragmatic function, such as declaratives, imperatives, and We share a commitment to this order of explanation. In this book we interrogatives, as definitionally grammatical categories (namely moods), will not argue separately for the rectitude of this order, but we hope to and only secondarily as pragmatic categories. Thus, such categories ap- demonstrate its fecundity. We think that only by beginning with discur- ply to sentences in virtue of their grammar, and one asks questions such sive practices can we understand, on the one hand, how discourse comes as "what can a person do with a declarative?"" to be responsive to the world and capable of expressing and commu- But in keeping with our commitment to the explanatory priority of nicating content, and on the other hand, how any practices manage to pragmatics, we define such use-indicating categories in terms of their use be practices of reason-giving, truth-telling, and responsibility-imputing, (which ought to seem quite a sensible approach, we think). Hence, for rather than just elaborate conventional dances. In this sense, we are cer- us, the answer to the above question is that what one can do with a de- tainly continuing a project with its lineage in the work of (in particular) clarative is—by definition—declare. This isn't to deny that we can iden- Brandom, Sellars, and Hegel. tify syntactic types as, for example, those that are typically or defeasibly However, authors like Brandom think not only that pragmatics is used to produce declaratival acts. But for us, this will be a secondary no- explanatorily prior to semantics and syntax, but also that the latter are re- tion. We always privilege pragmatic categories over grammatical catego- ducible to the former, that meaning just is a pragmatic feature of a speech ries when identifying the functional structure of a particular utterance. act, properly understood. The major project of Brandom's Making It Thus, rather than "What can one do with declaratives?", a question for Explicit is to spell out how semantics and syntax can be derived fully us (though not a particularly interesting one) will be "Which syntactic from pragmatics. In contrast, we remain steadfastly agnostic on issues of forms can function as declaratives in English?" semantic-pragmatic reduction. It is consistent with all we say that se- While our commitment to the pragmatist order of explanation puts mantics retain significant forms of autonomy from pragmatics. Tempting as it will surely be to some readers, we ask that our use of key Sellarsian 10. See H. P Grice's seminal paper, "Logic and Conversation," in Donald Davidson and and Brandomian terms and ideas such as the 'space of reasons' and 'com- Gilbert Harman, eds., The Logic of Grammar (Encino, Calif.: Dickenson, 1975), 64-75. The as- sumption that a 'pragmatics first" approach to language should follow the lines of G rice is mitments and entitlements' not be read as our implicit acceptance of this common. See for example Peter Grundy, Doing Pragmatics (New York: Oxford University Press, reductive move. 2000), a fairly standard introductory linguistics text that adopts the Gricean framework with- We assume that both mental states and speech acts are meaningful out discussion or argument.

Description: