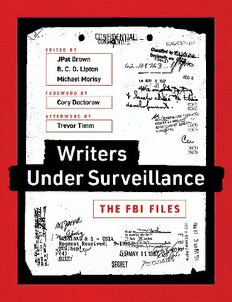

Writers Under Surveillance: The FBI Files PDF

Preview Writers Under Surveillance: The FBI Files

Writers Under Surveillance The FBI Files WritersUnderSurveillance.indb 1 6/22/18 10:53 AM WritersUnderSurveillance.indb 2 6/22/18 10:53 AM WritersUnderSurveillance.indb 3 6/22/18 10:53 AM © 2018 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Expo Serif Pro. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN: 978-0-262-53638-7 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 WritersUnderSurveillance.indb 4 6/22/18 10:53 AM Contents vii Foreword xi Introduction xiii Notes on Selections for this Collection xv Guide to Exemptions xvii Glossary 3 Hannah Arendt 9 James Baldwin 63 Ray Bradbury 79 Truman Capote 101 Tom Clancy 127 W. E. B. Du Bois 145 Allen Ginsberg 175 Ernest Hemingway 225 Aldous Huxley 237 Ken Kesey 263 Norman Mailer 289 Ayn Rand 307 Susan Sontag 327 Terry Southern 337 Hunter S. Thompson 357 Gore Vidal 373 Afterword WritersUnderSurveillance.indb 5 6/22/18 10:53 AM WritersUnderSurveillance.indb 6 6/22/18 10:53 AM Foreword The TradiTional jus TificaTion for open access laws goes like this: “We, the taxpayers, paid these government entities to produce the writings, images, videos and other materials that go into the formation of policy. These documents belong to us. We paid to produce them. We have the right to see them, to use them, to study them and share them. They are our property.” I love this argument, because I love free access to information, and this argument is very powerful. To refute this argument, a secrecy advocate must argue against property rights. In the 21st century, where property rights have been elevated to a human right — and even more, to the most important of all human rights — any argument that can only be refuted by denigrating property rights is a winning argument. If you want to win a debate, corner your opponent so they must argue against property rights (this is a lesson that is not lost on both sides of the copyright debate, and is the reason that “intellectual property” was promulgated as an alternative to the once-universal phrase “creators’ monopolies”). But the harnessing of government transparency to property rights is fraught with pit- falls. For one, information is almost entirely unlike property. Property is exclusive and excludable — when you leave my house after an evening’s socializing, you don’t take my house with you; when I tell you my secrets and then take my leave of you, there’s no way for me to take the secret back from your knowledge of it. Information has multiple uses and contexts. Your house is yours. Your phone number is an integer that can be found in the long string of numbers after the decimal in pi, in the ledgers of public companies, and in the software configuration and databases of your phone company’s switches. Your phone number is “yours,” but not in the same way that your underwear is. Assigning property rights to integers is a fool’s errand. The primacy of property rights at this moment is the reason we talk about information as property: anything valuable must be property. The way we assert value is to assert prop- erty rights. We are so trapped in this frame that we are unable to easily perceive it, but think for a moment of how we talk about the most valuable things in our lives: our children. Kidnapping is not “theft of child.” Infanticide is not “deprival of the use of a child.” Your child is not your property, and your child is also not their property — your child (and you, and me, and all the other humans) are not property, but we are all enmeshed in a web of interests, some bidirectional and some unidirectional. My daughter has an interest in herself; I have an interest in her too, as does my wife (who is her mother) and my parents and my wife’s parents, and our daughter’s godparents, and her teachers, and her friends, and Child Protective Services, and our neighbors. Some of those interests are stronger than others, and some are limited to narrow domains of our child’s life and wellbeing, but this WritersUnderSurveillance.indb 7 6/22/18 10:53 AM viii Writers Under Surveillance blend of overlapping, contesting interests is undeniable, and the fact that none of these are property rights in no way diminishes the value of that human life. Information, like humans, is not property, but it is incredibly valuable. Hence Steward Brand’s horribly misunderstood and brilliant aphorism: “On the one hand, information wants to be free, and on the other hand, information wants to be expensive.” Talking about government information as property is a handy way to win arguments with secrecy advocates who are also property-rights advocates, but it is a gross and ulti- mately harmful oversimplification. The state is not a business, and taxes are not a custom- er-loyalty program. If a piece of government information was produced before you paid your first penny in tax, you still have a right to see it. If you are a child who pays no tax, you still have an interest in state documents; if you are a poor person who pays little or no tax, you have the same right to government information as the one percenter who deigns to pay a million dollars in tax rather than hiding it with an offshore financial secrecy vehicle. The real reason we deserve to see the information our governments produce is so that we can understand what our states are doing in our names — not what they’re doing with our money. There’s no broad consensus on what constitutes good government, of course, but whatever you think of when you think of “good government,” you can’t know whether you have it unless you can pierce the veil of government secrecy. Knowledge allows you to observe the workings of the state and form a hypothesis about how to improve things. Knowledge allows you to recruit others to your cause by revealing the workings of the state and sharing your hypothesis. Knowledge allows you to evaluate whether your hypothesis was correct, revealing whether you improved things by trying your intervention out. The freedom to know, in other words, is the foundational freedom that gives us the freedom to do. But knowledge in and of itself is not enough. The right to know without the freedom to act on that knowledge is not empowering, it is a recipe for despair. Indeed, information without agency is a literal tactic of torturers: during the Inquisition, torturers engaged in a practice called “showing the instruments,” in which every implement that might be used in the coming torture session was lovingly revealed and shown to the victim, to heighten their anticipation of the horrors to come. Winston Smith knows exactly what’s in Room 101 and that is why he dreads it so much. Goldfinger’s laser slowly proceeds up the torture table towards James Bond’s crotch — rather than simply lancing through his chest-cavity — because Goldfinger wants Bond to suffer before he dies. But again, knowledge is our necessary precondition for improving even hopeless sit- uations. Knowing what rules the state imposes (that is, which laws are in force and what they say) is the precondition for effecting civil disobedience by skirting the law without breaking it. Knowing how the courts operate, or what procedures the police follow, or which ministries will not reveal their secrets, gives us the raw material for formulating plans to outmaneuver them, to reveal the shape of secrets by exploring the non-secret information that surrounds them: “If you won’t tell me the names of everyone who is a police informant, then tell me the names of everyone who isn’t one.” MuckRock’s users have remorselessly tugged at every loose thread in the fabric of official WritersUnderSurveillance.indb 8 6/22/18 10:53 AM Foreword ix secrecy, unraveling schemes and capers, as well as unintentional farces. MuckRock’s beauti- fully simple interface and community features do much to automate the process of not just forming hypotheses about shameful secrets; but also recruiting others to help act on them. Muckrock is the first step in the 21st Century’s great experiment in evidence-based rule, in the presumption of transparency, and in the use of transparency to effect change. This volume you hold now is an extrusion into the physical world of something vast and digital, huge in the way that only digital things can be huge, where adding another zero to an already inconceivably large number is as easy as typing a single keystroke. We have never in our species’ history possessed this sort of tool. It is a ferociously exciting prospect. As states move to assert the right to know more and more about our personal business, MuckRock represents the best hope for people knowing more and more about their states. It’s a race we can’t afford to lose. Cory DoCtorow WritersUnderSurveillance.indb 9 6/22/18 10:53 AM