Why don't west Louisiana bogs and glades grow up into forests? PDF

Preview Why don't west Louisiana bogs and glades grow up into forests?

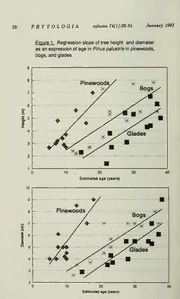

Phyiologia(Juraary1993)74(l):26-34. WHY DON'TWEST LOUISIANA BOGS AND GLADES GROW UP INTO FORESTS? i M.H. MacRoberts & B.R.MacRoberts Bog Research, 740 Columbia, Shreveport, Louisiana 71104 U.S.A. 1 ABSTRACT ! We studied trees in bogs, glades, and pinewoods in the Kisatchie NationalForest, Louisiana, to determinetree species sizeand density. Bogsandgladesarerelativelyopenhabitatswithstuntedtrees,many ofwhich are old growth. One reason why trees do not grow well in thesehabitatsinTolvesedaphicfactors. The soilisnutrient poor,itis underlainbyanimpermeablelayer,anditiseitherwaterloggedordry muchoftheyear. FireisprobablymoreimportantinIceepingbogsopen, whiledesiccationisprobablythemostimportantfactorforglades. KEYWORDS: Treegrowth,forest opening,bog, glade, Kisatchie NationalForest,Louisiana INTRODUCTION Thereare twonaturally open terrestrialhabitats in the Kisatchie Ranger District ofthe Kisatchie Nationad Forest. These are bogs, often referred to as hillside seepage bogs or pitcher plant bogs, and glades. Bogs are open, speciesrichenvironmentswhicharehydricbutnotinundated,andwhichhave acidic and nutrient poor soils. Glades are xeric, species poor environments often Mrith sandstone at or near the surface with thin nutrient poor acidic soils (MacRoberts & MacRoberts 1990, 1991, 1992a, 1992b; Frost et al. 1986; Martin & Smith 1991; Nixon & Ward 1986; Streng & Harcombe 1982). Inthispaperweaddress thequestion: whyarethesehabitatsopen? Since treesandwoody vegetationgrowinthemand both aresubject toinvasionby woody plants and herbaceous weeds, some factor or factors must be keeping this vegetationout (DeSeim 1986). Among reasons that havebeen suggested are fire frequency and intensity, poor soils, and hydric conditions. Streng & 26 i MacRoberts &MacRoberts.: Whydon't bogs andglades becomeforests? 27 Harcombe (1982), for example, have studied this problem in similar habitats in southeastern Texas and have found that edaphic factors may be responsi- ble for keeping grass/sedge meadows open, while pyric factors appear to be responsible for keeping bluestem savannas open. Other workers have made similar suggestions about various open habitats in theeastern United States (see Frost et oU. 1986; and Olson 1992; reviewsincludingrelevantliterature). METHODS Wemadefivesetsofobservations for this study. I. To compare the spatial distribution and size of trees in glades with those of bogs and pinewoods, we ran transects through the middle of five glades. Thesetotaledanarea416meterslongand3meterswide(1248 square meters). Within this areawemapped all treesover 1.5 meters tall,measured their diameter at breast height (dbh), auid recorded their species. We had previouslycollectedthesesamedatafor bogs and pinewoods (MacRoberts & MacRoberts 1990). II. We cut at ground level four small longleaf pines from each of three samplesofeachhabitat;thatis,atotaloftwelvetreesfrombogs, twelvetrees from glades, and twelvetrees from pinewoods. The sample was matched for size(treeheight and diameter)"and fortheamount ofsolarradiation received (thetwelvetreesfrompinewoodsweretakenfromareasthathadbeenclearcut, that had grown up sincethe cut; otherwise they would not havereceivedthe same solar radiation as trees from bogs or glades). The trees were measured and photographed and a cross section from the base of each was preserved for latermicroscopic examination. The purpose oftheseobservations was to determinethegrowth rateofpinesindifferent habitats. III.Wemadeincrementboringsofseven "relict"longleafpines(dbh28-38 cm) in two glades and one longleafpine (dbh 33 cm) in a pinewoods. Relict treesaretreesthatwerenot cutduringthe"bigcutover"thatoccurredinthe earlypartofthiscentury(Caldwell 1991); theyareoftenflat topped,stunted, and have few branches. Our purpose here a^ in II, was to gain insight into growth ratesoflongleafpinesinthesehabitats. IV.Ineachoffivegladesandfivebogswerandomlyselectedtentemporary onemetersquareplots,givingusfiftyonemetersquareplotsforeachhabitat. In each plot, we counted pine seedlings (first and second year plants) to see ifpine establishment differed among these habitats and could shed light on tree productivity. We did not collect the same data for pinewoods since it is obvious that pine germination is optimal in that habitat. We counted the treesintheplotsinJuly 1991. V. Wefollowed the fateofpineseedlings in four permanent plots: two in a glade and twoin a bog. The plots wereestablishedin March 1991 and re- 28 PHYTOLOGIA volume 74(l):26-34 January1993 Table 1. Numberoftreesbyspecies and theirsizeinglade transects. Species MsLcRoberts&:MacRoberts.: Whydon't bogs andglades becomeforests? 29 Table2. Treesizeinglade,pinewood, andbog transects. Diameter Class dbh (cm) 30 PHYTOLOGIA volume 74(l):26-34 JanuaryJ993 Figure 1. Regressionslopeoftreeheight anddiameter asanexpressionofagein Pinuspalustrisinpinewoods, bogs,andglades. 10 . 20 30 40 Estimatedage(years) 10 20 Estimatedage(years) MacRoberts&MacRoberts.: Whydon't bogs andglades becomeforests? 31 Table5. Treeringdataforglades, bogs, and pinewoods. Habitat 32 PHYTOL OGIA volume 74(l):26-34 January 1993 subject to periodic bums (Smith 1991; Olson 1992). In presettlement times, ] whilefiresprobablyoccurredonceeverytwotothreeyears,theywererelatively ] coolanddidnotkillallpineseedlings. However,theedaphicconditionsofbogs | (highly acidic, waterlogged, nutrient poor, impermeable bedrock) and glades ! (seasonally desiccated, hot, nutrient poor, impermeable bedrock) (Martin et I oL 1990) retard treegrowth, makingyoungtrees extremelyvulnerabletofire where herbaceous growth is extensiveas, for example, in bogs dominated by Cteniumandotherdenselygrowingherbaceousplants(seediscussioninStreng • k Harcombe 1982). Inourbogplots,whilepineseedlingssproutedandsurvivedwell,therewas j noevidencethat they continuedto survivebeyond theirfirst few years: slow |; growth makes them extremelyv\ilnerable to fires over many years. Longleaf . pinesarenotoriouslyslowgrowingintheirearlyyears,and although theyare resistsuit to fire, mortality is very high when the fire is hot (Schwarz 1907; Ij Mohr 1897; Wahlenberg 1946). Loblolly pines, while faster growing initially, areverysusceptibletofire. Inglades,seedlingsurvivalwaspoorbutbetterthanweexpected;however, thismayhavebeentheresultof1991 havingbeenanextremelywetyearvrith | drought infrequent and ofshort duration. Even so, in glades, most seedlings wereeitherscorchedbythesummersunordiedofdesiccationduringtheshort periods ofdrought. In theirexposed condition they weresubject not only to i the direct rays of the sun but to intense ground reflection. By November, the few survivors all had brown lower needles. Certainly seed production as measuredbyconeproductionwasadequateinthesetwohabitats. Largepines { inbothhabitatswereconeproducing,attestedtobygreenconesontreessuid ' byoldconeson thegroundfromprevious years. Inbothbogsandglades,itiscommontoencountertreesfelledbywindthrow,< erosion,orsaturationwiththeirshallowrootsystemsexposed. Suchmortality fromfallinginthesetwohabitatsisprobablyquitehigh,especiallyamongthe |j largertrees. Clearly,moreinformationonthelifehistoryoftreesinthesehabitatswould ' bewelcome. But,as anumberofworkershavepointedout,insteadoflooking ' for a set ofcommon factors, it is probably more profitable to recognize that i the pattern found in open habitat of a few stunted, gnarled, slow growing I trees is produced by widely differing causes. In bogs, fire is undoubtedly , important inthinningthetreepopulation since species areslow growing and ' therefore subject to many fires. Few escape to grow to maturity. In glades, fireis probablylessimportant sincelitteraccumulationisless extensivethan in bogs; desiccation caused by drought and prolonged sunlight are probably moreimportant. MacRoberts &MacRoberts.: Whydon't bogs andglades becomeforests? 33 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ThanksareduethestaffoftheKisatchieNationalForestfortheircoopera- tionandsupport duringthecourseofthisstudy,withspecialthanks toKaren Belanger,WildlifeBiologist,KisatchieRangerDistrict. D.T. MacRoberts and C.L.Liuaidedwithstatisticalmatters. D.T.MacRoberts andPaulHarcombe made many useful comments on an earlier version ofthe paper. Susan Carr, Botanist, KisatchieNational Forest, helped with thefigure. LITERATURE CITED Caldwell, J. 1991. Kisatchie National Forest: Part of a 100-year heritage. Forests & People41(l):35-46. DeSelm,H.R. 1986. NaturalforestopeningsofuplandsoftheeasternUnited States. InD.L. Kulhavy & R.N. Conner, eds., Wilderness andNatural Areasofthe Eastern UnitedStates: A Management Challenge. Pp. 366- 375. Center for Applied Studies, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas. Frost, C.C., J. Walker, & R.K. Peet. 1986 Fire dependent savannas and prairiesofthesoutheast. InD.L. Kulhavy& R.N. Conner,eds., Wilder- ness and Natural Areas ofthe Eastern United States: A Management Challenge. Pp. 348-357. Centerfor Applied Studies, Stephen F. Austin StateUniversity,Nacogdoches,Texas. MacRoberts, B.R. & M.H. MacRoberts. 1991. Floristics of three bogs in western Louisiana. Phytologia 70:135-141. MacRoberts,B.R.&M.H.MacRoberts. 1992. Floristicsoffoursmallbogsin westernLouisianawithobservationsonspecies/arearelationships. Phy- tologia 73:49-56. MacRoberts, M.H. & B.R. MacRoberts. 1990. Sizedistribution and density oftreesinbogsandpinewoodlandsinwestcentralLouisiana. Phytologia 68:428-434. MacRoberts,M.H.&B.R.MacRoberts. 1992. Floristicsofasandstoneglade inwestern Louisiana. Phytologia 72:130-138. Martin, D. & L.M. Smith. 1991. A survey and description of the natural plantcommunitiesoftheKisatchieNationalForest: WinnandKisatchie Districts. Unpublishedreport,LouisianaNaturalHeritageProgram,De- partment ofWildlifeand Fisheries, Baton Rouge, Louisiana. PHYTOLOGIA 34 volume 74(l):26-34 January 1993 Martin, P.G., C.L. Butler, E. Scott, J.E. Lyles, M. Marino, J. Ragus, P. Mason, & L. Schoelerman. 1990. Soil survey of Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana. United States Department ofAgriculture, Soil Conservation Service. Mohr, C. 1897. Timber Pines ofthe Southern United States. U.S. Depart- ment of Agriculture, Division of Forestry. Bulletin 13. Washington, D.C. Nixon, E.S. & J.R. Ward. 1986. Floristic composition and management of east Texas pitcher plant bogs. In D.L. Kulhavy & R.N. Conner, eds.. Wilderness andNaturalAreas ofthe Eastern UnitedStates: A Manage- ment Challenge. Pp. 283-287. Center for Applied Studies, Stephen F. Austin State University,Nacogdoches, Texas. Olson,M.S. 1992. Effectsofearlyandlategrowingseasonfiresonresprouting ofshrubsinuplandlongleafpinesavannasandembeddedseepagesavan- nas. M.Sc. thesis. Louisiana StateUniversity,Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Schwarz, G.F. 1907. The LongleafPine in Virgin Forest. John Wiley, New York, NewYork. Smith, L.M. 1991. Louisiana longleaf, an endangered legacy. Louisiana Conservationist May/June24-27. Streng, D.R. & P.A. Harcombe. 1982. Whydon't east Texas savannas grow upintoforests? Amer. Midi. Naturalist 108:278-294. Wahlenberg, W.G. 1946. LongleafPine. U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Depart- mentofAgriculture. Washington, D.C.