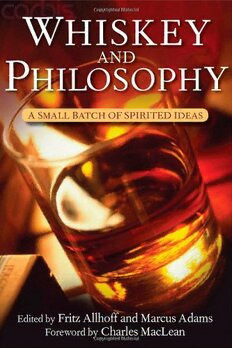

Whiskey and Philosophy: A Small Batch of Spirited Ideas (Epicurean) PDF

387 Pages·2009·1.74 MB·English

Most books are stored in the elastic cloud where traffic is expensive. For this reason, we have a limit on daily download.

Preview Whiskey and Philosophy: A Small Batch of Spirited Ideas (Epicurean)

Description:

I consider myself a connoisseur of only two things; sushi and whisky. This might seem like an odd combination, but Scotland and Japan are the two countries I have lived in besides my native US, and I gained a deep appreciation for both traditions. And make no mistake, Japan is whisky country. In fact, the finest single malt whisky in the world is made in Japan. Don't believe me? Just take a look inside "Whiskey and Philosophy."

What is "Scotch" anyways? What is "whisky?" (Or "whiskey", if you prefer. A debate in and of itself.) These are some fundamental questions that have not really been asked. By law, Scotch must be produced in Scotland, but if you take all the same ingredients and techniques, move them to another country and produce a product that is indistinguishable and in fact superior to the original (as Japan did), what do you call it? How much can you change the ingredients before what in your bottle is no longer considered whisky? Can you add flavorings and colors as has been done to vodka? And what is meant by a "great" whisky? Isn't it just a question of personal taste? Is there such a thing as a perfect "Platonic" Manhattan, or is variety the spice of life? Is drinking whisky a feminist statement? And how does Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle factor into all this?

These, and more, are the kinds of questions asked in "Whiskey and Philosophy." In fact almost no stone is left unturned. Even the title, willfully choosing the "e" spelling denoting bourbon, is a conscious choice supported by debate. For too long, authors Fritz Allhoff and Marcus P. Adams say in the introduction, the American-made whiskeys like bourbon and rye have been considered lower-shelf than their overseas cousins the Scotch and the Irish. Bourbon was a drunkard's tipple, dumped in with coke to mask the taste, and not something to be praised alone. With the very title of the book that sought to change that.

There are five units in total, with several articles in each waxing historical, philosophical or political about the water of life. Some, like Andrew Jefford's "Scotch Whisky: From Origins to Conglomerates" go a long way to bursting some popular bubbles about Scotch whisky. Although appreciators like to pat themselves on the back for their refined tastes, but in reality 90% of scotch whiskey produced gets dumped into those distained blended Scotches which still account for the vast amount of sales of Scotch whisky. Only 10% is bottled and sold as Single Malt. The illusion of a hand-crafted product from wind-swept shores is also shattered with images of modern production facilities and a Master Distiller whose job involves more button-pushing on complex machines rather than nosing a glass and wistfully bidding goodbye to the Angel's Share. Other fantastic articles like Ian J. Dove's "What do Tasting Notes Tell Us?" talks about the subjective nature of all those "overtones of clove and heather" or "scents of fruit at the market" -type of talk you see in tasting books. Should we feel bad if we can't separate the sensations? Richard Menary thinks so, in his article "The Virtuous Whisky Drinker and Living Well" who makes the separation between "virtuous" drinkers who study the product and refine their skills, with those who merely imbibe for alcoholic pleasure. (A split I thought summed up very well in Chasing the White Dog when it was said that "sometimes I am tasting, but sometimes I am just drinking.")

Many of the articles on Scotch focused on Islay, which was fine with me as that is my favorite whisky region, but even then there is some myth-busting going on. Labels like Laphroaig are in fact owned by large spirit conglomerates like Fortune Brands, and while the whisky is distilled on Islay it is actually aged over on the mainland so there is very little opportunity for that "lashed by the sea" taste to creep in during the aging process. When you make your whisky choice, you are buying marketing and an image as much as you are buying the spirit itself.

Some of these essays got me thinking. Some of them confused me. Some of them ticked me off. Which is exactly the correction reaction for a book like this. There were a few, I must confess, which bored me. Ada Brustein's "Women, Whiskey and Libationary Liberation" with its comments on feminism and whiskey drinking didn't do much for me, but I am probably not the target audience. "Whisky and the Wild" by Jason Kawall attempting to apply biological genus/species categorization and wondering whether diversity of product inherently improves the market took the metaphor a bit far for me, as did Dave Monroe's musings on the ability of whiskey to "make a man mean" in "Nasty Tempers: Does Whiskey Make People Immoral?" Christ Bunting's history of "Japanese Whisky" was one of my favorites, as was Harvey Siegel's personal memoir on finding the spot in Scoland "Where the Fiddich Meets the Spey."

"Whiskey and Philosophy" is part of a series of books, including Wine and Philosophy and Food and Philosophy. This is a truly spectacular book, and a gift to whisky aficionados everywhere. If there is someone who loves whisky, I couldn't imagine them not wanting to have a copy of "Whiskey and Philosophy" in their library.

The only possible complaint I have about this book is I wish I could have been a contributor instead of just a reader! You can't read something like this without your own ideas popping into your head. Ah well, maybe when it is time for "Sushi and Philosophy" to come out...

See more

The list of books you might like

Most books are stored in the elastic cloud where traffic is expensive. For this reason, we have a limit on daily download.