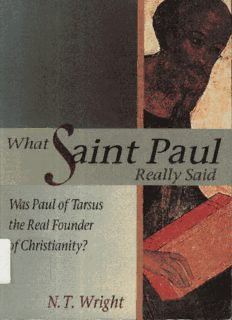

What Saint Paul Really Said: Was Paul of Tarsus the Real Founder of Christianity? PDF

Preview What Saint Paul Really Said: Was Paul of Tarsus the Real Founder of Christianity?

WHAT SAINT PAUL REALLY SAID For Keith Sutton WHAT SAINT PAUL REALLY SAID N. T. WRIGHT WAS PAUL OF TARSUS THE REAL FOUNDER OF CHRISTIANITY? WILLIAM B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING COMPANY GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN FORWARD MOVEMENT PUBLICATIONS CINCINNATI, OHIO Copyright © 1997 N. T. Wright First pubhshed 1997 in the U.K. by Lion Publishing pic Sandy Lane West, Oxford, England ISBN 0 7459 3797 7 Albatross Books Pty Ltd PC Box 320, Sutherland, NSW 2232, Australia ISBN 0 7324 1648 5 This edition published joindy 1997 in the United States of America by Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company 255 Jefferson Ave. S.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49503 and by Forward Movement F^lbUcations 412 Sycamore Street, Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 02 01 00 99 98 97 7 6 5 4 3 2 Library of Congress Catak>ging-in-Publication Data Wright, N. T. (Nicholas Thomas) What Saint Paul really said: was Paul of Tarsus the real founder of Christianity? / by Tom Wright, p. cm. Based on various lectures given at various places and times. Includes bibliographical references. Eerdmans ISBN 0-8028-4445-6 (pbk.: alk. paper) Forward Movement ISBN 0-88028-181-2 1. Bible. N.T. Epistles of Paul—^Theology 2. Paul, the Apostle, Saint. 3. Christianity—Origin. I. Title. BS2651.W75 1997 225.9'2—dc21 97-8588 CIP Contents Preface 7 Chapter 1 - Puzzling Over Paul 11 Chapter 2 - Saul the Persecutor, Paul the Convert 25 Chapter 3-Herald of the King 39 Chapter 4 — Paul and Jesus 6i Chapter 5 — Good News for the Pagans 77 Chapter 6 — Good News for Israel 95 Chapter 7 - Justification and the Church 113 Chapter 8 - God's Renewed Humanity 135 Chapter 9 - Paul's Gospel Then and Now ISl Chapter 10 — Pavd, Jesus and Christian Origins 167 Annotated Bibliography 185 Preface Paul has provoked people as much in the twentieth century as he did in the first. Then, they sometimes threw stones at him; now, they tend to throw words. Some people still regard Paul as a pestilent and dangerous fellow. Others still think him the greatest teacher of Christianity after the Master himself This spectrum of opinion is well represented in the scholarly literature as well as the popular mind. I have lived with St Paul as a more or less constant companion for more than twenty years. Having written a doctoral dissertation on the letter to the Romans, a commentary on the letters to the Colossians and to Philemon, and a monograph on Paul's view of Christ and the law — not to mention several articles on various passages and themes within Paul's writings — I still have the sense of being only half-way up the mountain, of there being yet more to explore, more vistas to glimpse. Often (not always), when I read what other scholars say about Paul, I have the feeling of looking downwards into the mist, rather than upwards to the mountain-top. Always I am aware that I myself have a good deal more climbing yet to do. The present book is therefore something of an interim report, and an incomplete one at that. My large volume, in which I hope to do for Paul what I have tried to do for Jesus in Jesus and the Victory of God (SPCK and Fortress, 1996), is still in preparation. But I have lectured on certain aspects of Paul's thinking in various places over the last few years, and several of those who heard the lectures have encouraged me to make them available to a wider audience. I am very grateful for the invitations to give the Selwyn Lectures in Lichfield Cathedral, the Gheens Lectures at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, the Prideaux Lectures at Exeter University, and some guest lectures at Asbury Seminary, Kentucky and at the Canadian Theological Seminary in Regina, Saskatchewan. My hosts were enormously hospitable, my audiences enthusiastic, and my questioners acute and probing, on each of these occasions. I am deeply grateful. In pulling these various lectures together into a single whole, I am very WHAT ST PAUL RLALLY SAU) conscious that there are large swathes of Pauline thought still untouched. This book is not, in other words, in any sense a complete study of Paul. It does not attempt even to be particularly 'balanced'. What it does attempt to do, however, is to focus on some key areas of Paul's proclamation and its implications — including some not usually noticed — in an attempt to uncover 'what St Paul really said' at these vital points. A few notes about some basic matters. There has been endless debate as to how far the Paul of the letters corresponds, or does not correspond, to the Paul we find in the Acts of the Apostles. I shall not engage in this debate here, though my analysis of what Paul was saying at key points in his letters may eventually turn out to have some bearing on the issue. Likewise, people still discuss at length whether Paul actually wrote all the letters attributed to him. Most of what I say in this book focuses on material in the undisputed letters, particularly Romans, the two Corinthian letters, Galatians and Philippians. In addition, I regard Colossians as certainly by Paul, and Ephesians as far more likely to be by him than by an imitator. But nothing in my present argument hinges on this one way or the other Apart from a few essential notes, 1 have not attempted to indicate the points at which I am building on, or taking issue with, colleagues within the discipline of Pauline studies. The detailed foundations of my argument can mosdy be found in my own various published writings. These, and other works which may be helpful for fiirther study, are listed in the bibliography Scholarly colleagues will realize that the present work is not attempting to be a learned monograph; non-scholarly readers will perhaps forgive me my occasional forays into what seem to me, though they may not to them, necessary diversions and complexities. After the work on this project was more or less complete, there appeared (in a review copy, sent to me at proof stage) a new book by the English journalist, novelist and biographer A.N. Wilson. He revives the old argument that Paul was the real founder of Christianity, misrepresenting Jesus and inventing a theology in which a 'Christ' figure, nothing really to do with the Jesus of history, becomes central. Since this theory turns up regularly in one guise or another, and since what I wanted to say in this book anyway forms the basis for the reply I think should be made, I have added at the end a chapter dealing with the whole issue, and with Wilson's book in particular There are, of course, plenty of books that deal with this issue at great length, and I shall not attempt to duplicate their discussion. The Bishop of Lichfield, the Right Reverend Keith Sutton, invited me to

Description: