Wartime Notebooks: France, 1940–1944 PDF

Preview Wartime Notebooks: France, 1940–1944

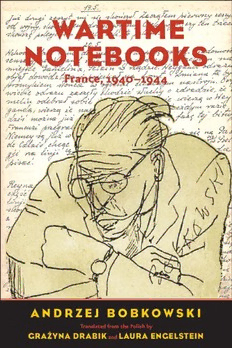

Wartime Notebooks This page intentionally left blank Wartime Notebooks France, 1940–1944 ANDRZEJ BOBKOWSKI TRANSLATED FROM THE POLISH BY GRAZ˙YNA DRABIK AND LAURA ENGELSTEIN YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW HAVEN & LONDON The Margellos World Republic of Letters is dedicated to making literary works from around the globe available in English through translation. It brings to the English- speaking world the work of leading poets, novelists, essayists, philosophers, and playwrights from Europe, Latin America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East to stimulate international discourse and creative exchange. English translation copyright © 2018 by Grażyna Drabik and Laura Engelstein. Originally published as Szkice Piórkiem. Copyright © Henryk Boukolowski and Wydawnictwo CiS, 2011. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e- mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office). Set in Electra and Nobel type. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2018936160 ISBN 978- 0- 300- 17671- 1 (hardcover : alk. paper) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48- 1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Introduction, by Laura Engelstein vii 1940 3 1941 175 1942 244 1943 379 1944 520 Afterword: Out of This Nettle, by Grażyna Drabik 592 Acknowledgments and Translators’ Note 603 Notes 605 Index of Names 653 Illustrations follow pages 174, 378, and 560 This page intentionally left blank INTRODUCTION Laura Engelstein Andrzej Bobkowski, an aspiring young Polish writer, found himself in Paris when the Germans invaded France in May 1940. For the next four years and three months, until August 1944, he kept a journal. He followed the progress of the war as reported in the press and in radio broadcasts, as reflected in rumors and the fears of people he met in his daily life; he read widely in both French and German and reflected on European history and culture. Safe on the home front, he ate, he drank, he smoked, he swam and bicycled. He thought of him- self as a free spirit and developed a vivacious prose style on the handwritten page that expressed his desire to break with social and literary conventions. After the war, Bobkowski did not return to Poland, by then under Communist rule. His wartime notebooks were published in Paris in 1957 but, for reasons connected to the politics of postwar Europe, did not attain a Polish readership until Com- munism had ended. Once discovered in his homeland, Bobkowski was hailed as a bright new voice in Polish letters. A literary hero was born. Opening the translation of Bobkowski’s 1957 text, English- speaking readers will be fascinated to encounter a writer whose work remains fresh and surpris- ing in its native context, even half a century after it was written. They will be fascinated by the unusual perspective his testimony provides, the outlook of an intellectual from the cultural margins of Europe who did not take Europe for granted. On the one hand, he was at the center of things. “Paris,” as he later wrote, “was at the time an excellent observation post. The perfect armchair.”1 Bobkowski had come to Paris with his wife, Barbara, and the couple felt them- selves very much alone, but they were not isolated. Bobkowski’s observations reflect his wide social networks, both among the Polish emigration and among French acquaintances, neighbors, and colleagues. His omnivorous cultural appetite, embracing theater, music, the cinema, literature, philosophy, and politics, also offers a portrait of the historical moment. On the other hand, the occupant of that well- placed armchair was not a native Parisian but a visitor from Eastern Europe, a culturally amphibious outsider, able to observe his sur- roundings with a knowing but distanced eye. Readers will be intrigued as well by the complexity of Bobkowski’s profile. Nothing is simple when it comes to vii viii Introduction this writer—neither his biography nor his persona, neither the saga of the note- books’ publication nor the story of their reception in the Polish- speaking world. So, who was Andrzej Bobkowski? This son of Poland was born on October 27, 1913, in Wiener Neustadt, Austria, where his father, an officer in the imperial Habsburg army, taught at the military academy. His early years, spent in Poland, coincided with those of World War I, the establishment of the Second Polish Republic in 1918, and the Polish- Soviet War of 1919–1921, in which his father served as chief of staff of an infantry division in the Polish army. The young man attended Gymnasium first in Toruń, then Cracow, where his mother was closely tied to theatrical and artistic circles and his father to the regime inaugurated by Józef Piłsudski in 1926.2 From 1933 to 1936, he studied economics at the War- saw School of Economics and in December 1938, he married Barbara Birtus, known as Basia, whom he had met in Cracow.3 In March 1939, the couple left Poland for Paris, where Bobkowski was to take an internship arranged by the Polish Ministry of Commerce and Trade, with the goal of an eventual posting in Buenos Aires, Argentina.4 But history was closing in. On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland from the west; on Septem- ber 17, 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east; on September 27, 1939, Warsaw surrendered to the Germans. After a mere twenty years of inde- pendence, the Second Polish Republic ceased to exist. The French Third Re- public was soon to follow. On May 10, 1940, the Germans invaded France; on June 14, Paris surrendered. A week later Germany signed an armistice with the regime of Marshal Philippe Pétain and France was divided into the northern zone of occupation, including Paris, and the so- called zone libre in the south. On September 7, 1939, Bobkowski had volunteered for the Polish army in France, but was rejected, and thus deprived, as he wrote sardonically, of the chance to die for the fatherland. Instead, he busied himself with a more mun- dane service. From February 1940 until August 1944 he worked for a special Polish Bureau created by the Paris office of the war industries section of the Polish Finance Ministry. The Polish Bureau was attached to the Atelier de Con- struction, a French munitions factory in the Parisian suburb of Châtillon, which employed Polish workers. An attempt to ship its personnel to England in June 1940 failed; instead, workers and staff were evacuated to the south of France in September 1940. Bobkowski accompanied the relocation but returned to his office in Paris, where, under the pretext of liquidating the Atelier’s commer- cial affairs, he and his colleagues provided systematic support, financial, legal, and social, for Polish workers remaining in the occupied zone.5 After the war, Bobkowski stayed in Paris, engaged in various occupations—editing a Polish- language journal, working for a bookstore, for the YMCA, and seeing a few short pieces into print. Introduction ix Crucially, Bobkowski established an enduring connection with the most im- portant center of Polish intellectual life outside Poland, the publishing house of Kultura, after 1947 established in Maison-L affitte, near Paris. Its journal, Kul- tura, was modeled on Alexander Herzen’s Russian Free Press of the 1850s, an outpost of free thinking beyond the reach of autocrats and official ideologues.6 Its director, Jerzy Giedroyc, saw Kultura’s mission as one of “widening the Polish arena for debate with the introduction of fresh ideas,” even across the divide of Communist Poland.7 Kultura published a broad range of authors, in Polish and in translation, including such writers of international stature as Czesław Miłosz, Leszek Kołakowski, and Witold Gombrowicz. Giedroyc would emerge as the publisher of Bobkowski’s Notebooks and as the writer’s lifeline to Europe, be- cause in 1948 the Bobkowskis finally boarded ship, heading, not for their origi- nal destination, but for Guatemala, where they settled with barely a penny to their name and not a word of Spanish. There, Bobkowski ran a shop for model airplanes, a lifelong passion, from which he eked out a living, maintained an active correspondence with Kultura and with friends and family left behind, and continued his literary projects, including revisions of the Notebooks for publication. He died of brain cancer on June 26, 1961; Barbara Bobkowska re- mained in Guatemala until her own death in 1982. When Bobkowski began filling his copybooks in May 1940, writing in a sure and steady hand on lined paper, he was twenty- six years old. His pathway to authorship and recognition was to be long and twisted. Immediately after the war, he published a few fragments from the notebooks in a Cracow-b ased lit- erary journal and a piece in Kultura. In 1948, he offered the complete volume to the Communist- run publisher Czytelnik in Warsaw, but the manuscript was rejected. Finally, he gave the Notebooks to Kultura. “What a pain to deal with publication across an ocean,” he complained to Giedroyc, while the text was in preparation.8 He had hopes it might be a hit (a szlagier).9 One thing for sure, it would be “monstrously fat—a damn brick.”10 Indeed, it appeared in two vol- umes. Preserving the journal’s episodic form, Bobkowski called the published version Szkice piórkiem (Francja 1940–1944)—Pen Sketches: France, 1940– 1944, or Wartime Notebooks, as we have titled them.11 The “brick” in two volumes was barely noticed at the time. Only in the 1980s did articles begin appearing in Polish journals recognizing Bobkowski’s exis- tence. An eminent literary scholar described the Notebooks as an “unknown masterpiece” of modern Polish prose, a fresh voice in Polish letters.12 In 1985 a Polish- language publisher in London reprinted the Kultura edition, which was followed in 1987 and 1988 by underground versions inside Poland, as the Com- munist regime was losing its hold. A volume of his stories appeared in Paris in 1970 and in Warsaw in 1989, after the regime had fallen. The Notebooks them-