Walk on the water PDF

Preview Walk on the water

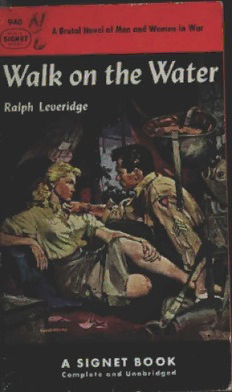

"Now he looked at her, his eyes traveling up and down her body. As used to the stares of men as she was, Norah felt she had never known so intense or complete a scrutiny •.• He seemed to be searching. For what? She suddenly wondered. Strength or weakness?" Love and Death Norah Calhoon met Sergeant Hervey when he was hospitalized behind the lines. She feared, and yet was irresistibly attracted to his overpowering mascu linity, and in a few wonderful weeks they packed the emotions and intensities of a lifetime. But when Hervey's wounds healed, he chose to return to the lurking death and filth of the Pacific jungles to rejoin his squad because of his loyalty to his men. To all the men-the cowards, the heroes, the brutes, the weaklings-the men who had died and the men who were still living and depended on him for lead ership. This is a stinging picture of war at its rawest, a book whose tragic pity and understanding creates an unfor gettable picture of men and women at their worst and best. "The book's primitive details indicate what some times can be unbearable about the Army-not the enemy, not even the physical discomfort, but the continual assaults on a man's sensitivity." -The New York Timt>s Other Signet Books You Will Enjoy THE LovED AND THE LosT by Morley Callaghan A beautiful young white girl's tragic attempts to crash a Negro world. (Signet #944-25c) FINISTERE by Fritz Peters A fascinating, sensitive portrayal of a young man's tragic world. (Signet #930-25c) A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE by Tennessee Williams The famous Pulitzer Prize play of a woman betrayed by love. Illustrated with scenes from the New York, London and Paris productions. (Signet #917-25c) THE STRANGE LAND by Ned Calmer A savage novel of the men and women who fight, love and die in war. (#5851-A Signet Giant-35c) THE NAKED AND THE DEAD by Norman Mailer A handful of fighting men on a Pacific Island and the women and events that shaped their lives. ( #837AB-A Signet Double Volume-SOc) TO OUR READERS: We welcome your comments about any Signet or Mentor book, as well as your suggestions for new reprints. If your dealer does not have the books you want, you may order them by mail, enclosing the list price plus 5c a copy to cover mailing costs. Send for a copy of our complete catalogue. The New American Library of World Literature, Inc., 501 Madison Ave., New York 22, N. Y. -- WALK On The WATER .. By Ralph Leveridge A SIGNET BOOK Published hy THE NEW A:\IERICAN LIBRARY CoPYRIGliT 1951 BY FARR~, STRAUS & YOUNG, INc. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or any portions thereof. - Published as a SIGNET BOOK By Arrangement with Farrar, Straus & Young, Inc. FIRST PRINTING, JUNE, 1952 SIGNET BOOKS are published by The New American Library of World Literature, Inc. 501 Madison Avenue, New York 22, New York PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA I say more: the just man justices; Keeps grace: thiit keeps all his goings graces: Acts in God's eye what in God's eye he is Christ-for Christ plays in ten thousand places, Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his To the Father through the features of men's faces. From the Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins, COURTESY OF THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS / TO the woman of Sherwood Forest and ro the woman of Charlottesville BOOK ONE I IT had not stopped raining for a week, except for brief intervals. Sometimes it was a furious downpour, the rain-spots stinging their hands and faces, as hail will sting. Sometimes it was a soft, multitudinous drizzle, a morning mist of rain. But always it was there, a relentless thing. At last it seemed that its roar was a liquid poured intq their ear drums, pressing against the membranes, tightening the hard sense of suffocation within their hearts, building a scream that somehow was never released. Their uniforms were like wet dishrags, slopped around their bodies; and is they paced, re volvingly, the tiny confines of their foxholes, these soggy clothes washed them. And they did not want to be washed. They wanted to stay dirty, for in dirt there was a comfort. Dirt was allied to what they were going through. Cleanliness was something foreign now; something belonging to the lost Amer ica of fresh white sheets and newly laundered underwear, of summer cotton and red lips and pink breasts, something tor menting when known beside the now habitual filth, mud, stale blood and dead rotting bodies. So they wanted dirt. They had to have dirt-as their beards and itching scalps and sweating feet suggested dirt. Instead, there was the monsoon, and soggy clothes insidiously cleaning their bodies to leprosy white. Be cause of this they raved and, raising their tired eyes to the clouds, their fists clenched and tears in their voices, groaned aloud. But still the rain poured down. If anything, it mocked the blasphemy that was the GI prayer. First it was a roar, then a soft murmur, as irregular in sound as the China Sea beating on the shore. It was hot and, despite the impetuous wind, heavy with humidity. Cailini had said, before falling into a dream filled sleep, that it was like swimming in an already dead sea. Hervey, his buddy and foxhole partner, heard but did not re ply. The full tiredness that shrouded him would not even let him nod an appreciation. But the moment he heard Cailini's soft snore, he turned swiftly. The sight of Cailini sleeping was almost more than he could bear. He lifted his foot and was about to kick the sleeping man when he saw Cailini's arms suddenly, uncontrollably, jerk. Hervey stopped then and, look ing down at the tired, war-dissipated face, felt a fierce onrush of tenderness. His hand reached out, and he stroked Cailini's forehead lightly, as if he hoped to wipe away his friend's dream. He knew, watching Cailini, reality had pursued him into sleep. There was no escape from the nightmare. After a minute he forgot Cailini and leaned against the rear wall of the foxhole. With his fingers and palms Hervey began slowly to massage his own face. He had never been more tired and, strangely, never more awake. With his fingers he pressed his stinging eyes deep into their sockets. He ran his hands over the puffy bags under his eyes. Carefully he explored the mouth line tangents, the crow's-feet and forehead wrinkles. His sudden vanity swore they were as deep as scars. He wondered how war-old his face really was. Suddenly impatient with himself, he shouted aloud, "Who the hell gives a shit?" His answer came ringing back, "You do! You do!" And what was really he, said, "Well, there's not a goddamn thing you can do about it." A sound ahead of him stopped his brooding. Swiftly he peered through the camouflage, but there was nothing in No Mao's Land or beyond to betray the existence of Japs. All that could be seen were masses of thick, opulent vegetation, greener than any emerald; stumpy incongruous banana trees; closely knitted bamboo clumps and lanes of stately coconut trees that looked like cathedral naves. Thick, juicy mud was everywhere, a deep and tenacious gum upon the earth. It was caked on the squad's clothes; it clogged their weapons, reducing the effi ciency of high-speed fire. Especially was it concentrated in the foxholes, which were not so much boles as depressions punched by a giant fist in the soggy terrain. Hervey began to raise himself, taking care that his head did not appear above the camouflage. He looked to the right. The neighboring foxhole was empty. Even the bloodstains that earlier had been splashes of red on the brown and the greens were gone now. Hervey wanted to call out, to shout Gruber's name, for he still had a feeling that the boy was somewhere in the foxhole. In his mind there persisted a picture of Gruber, alive, sleeping and hidden from sight-a far more vivid picture than the finality of a bursting mortar shell and Gruber's limbs flying up, out, around. It took Hervey almost a minute to re member, and then the sensation he was growing to know more and more closed over him again. It was as though his body were ice, and that ice on fire. In the startling silence that had 8 followed tl;le explosion, Rosinski, his eyes dilated and his Adonis face stretched tight against his bones, had shouted, "They got Gruber!" Adams had muttered a tired, "That's bad." Noth ing more. Lunagan, who had winced involuntarily, listened to his partner, Tuthill, voice a laconic, "Tough! But what the. hell does Rosinski expect us to do about it?" Polson, the big farmer, said three times that it was an awful thing, but five minutes later his mind was back in Ohio, speculating on the current bean crop. Hervey himself had raised his fist in the enemy's direction, shaken it savagely, shouted every obscenity he could think of and then, as abruptly, had shut up. Wearily he had turned to Cailini. "What's the use? What's the goddam use?" Cailini nodded his head. There was nothing to say. Hervey had said it all. Bill Hervey now stared hard at the empty hole, but as hard as he stared he could see none of the brilliant red that an hour before had marked the brown and the ·greens. He moved restlessly, briefly folded his arms, felt the sergeant stripes against his sopping uniform. He thought of his mother, or, as he called her, Emmy. He remembered her crisp humor, her concern because he drank too much Scotch and would not get a job, marry and settle down as so many of his friends had. He remembered the nights he had lain on her bed and talked until dawn. He wished he were on that bed now. Then he re membered his father-the Senator, Bill and Emmy called him. Though he was actually a senator, the title was infused with a hundred private mocking connotations. The Senator was a showman and a pompous ass, listening to and in love with each rhetorical spiel he made. Words. Rivers of words that became oceans the moment he opened his mouth. And when the press glowed, Emmy and Bill, looking quietly at each other, said nothing, but grew to understand each other more. He often thought about his mother, and then his fear was like the big dip on a roller coaster. These were the only times he was fille'tl with panic, the times when he was sure she would never see him again. Now, on looking back, he knew she could not live when the hope of reunion was gone. It would have been different if .the Senator had been a lover, or a man. In stead, he was something attached through a ceremony, some thing irrevocably hers (or she his) because they had made a mistake, and the scheme and pattern of their lives said there must be no repairing. He, Bill, her one child, had taken the place of a lover. He had eased her loneliness, mostly by being 9