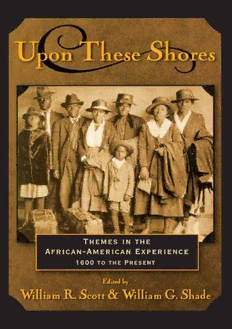

Upon these Shores: Themes in the African-American Experience, 1600 to the Present PDF

Preview Upon these Shores: Themes in the African-American Experience, 1600 to the Present

Upon These Shores 2 Upon These Shores THEMES IN THE AFRICAN-AMERICAN EXPERIENCE 1600 TO THE PRESENT Edited by William R. Scott & William G. Shade 3 Published in 2000 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue New York, NY 10017 Published in Great Britain by Routlege 2 Park Square, Milton Park Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Copyright © 2000 by Routledge Design: Jack Donner All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress cataloging-in-Publication Data Scott, William R. (William Randolph), 1940– Upon these shores : themes in the African-American experience, 1600 to the presen / William R. Scott and William G. Shade. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–415–92406–5 ISBN 0–415–92407–2 (pbk.) 1. Afro-Americans—History. 2. Afro-Americans—Histroriography. I. Shade, William G. II. Title. E185.S416 2000 973’.0496073—dc21 99–034688 4 To the students and staff of the United Negro College Fund and Andrew W. Mellon Minority Fellows Program 5 … voyage through death to life upon these shores. —From “Middle Passage” by Robert Hayden 6 contents Foreword William H. Gray III Chronology of African-American History Introduction The Long Rugged Road William R. Scott and William G. Shade part 1. out of africa 1. Africa, the Slave Trade, and the Diaspora Joseph C. Miller part 2. this “peculiar institution” 2. Creating a Biracial Society, 1619–1720 Jean R. Soderlund 3. Africans in Eighteenth-Century North America Peter H. Wood 4. In Search of Freedom Slave Life in the Antebellum South Norrece T. Jones Jr. 5. “Though We Are Not Slaves, We Are Not Free” Quasi-Free Blacks in Antebellum America William G. Shade part 3. the reconstruction and beyond 6. Full of Faith, Full of Hope The African-American Experience from Emancipation to Segregation Armstead L. Robinson 7. Blacks in the Economy from Reconstruction to World War I Gerald D. Jaynes 8. In Search of the Promised Land Black Migration and Urbanization, 1900–1940 Carole C. Marks 7 9. From Booker T. to Malcolm X Black Political Thought, 1895-1965 Wilson J. Moses 10. Rights, Power, and Equality The Modern Civil Rights Movement Edward P. Morgan part 4. african-american identity and culture 11. The Sounds of Blackness African-American Music Waldo F. Martin Jr. 12. Black Voices Themes in African-American Literature Gerald Early 13. Black Religious Traditions Sacred and Secular Themes Gayraud S. Wilmore part 5. family, class, and gender 14. African-American Family Life in Societal Context Crisis and Hope Walter R. Allen 15. From Black Bourgeoisie to African-American Middle Class, 1957 to the Present Robert Gregg 16. The New Underclass Concentrated Black Poverty in the Postindustrial City John F. Bauman 17. Black Feminism in the United States Beverly Guy-Sheftan part 6. the postwar agenda 18. African Americans and Education since the Brown Decisions A Contextual View Stephen N. Butler 19. After the Movement African Americans and Civil Rights since 1970 Donald G. Nieman 8 20. The Quest for Black Equity African-American Politics since the Voting Rights Act of 1965 Lawrence J. Hanks 21. Black Internationalism African Americans and Foreign Policy Activism William R. Scott Afterword The Future of African Americans Charles V: Hamilton Notes on Contributors 9 Foreword William H. Gray III I T GIVES ME GREAT PLEASURE to write this foreword to an important I and timely book on Americans of African descent. This anthology on I various aspects of the black experience, past and present, appears toward the end of an era of enormous change in the status of America’s largest racial minority. The essays in this collection are informed by a deep sense of the long journey our people have traveled since being forcibly brought to these shores in chains. It is fitting that this book should appear at the end of the twentieth century because these are both triumphant and troublesome times for black Americans. We must pause at this point and reflect on both our trials and our triumphs and how we must confront remaining challenges. As we try to judge the position of African Americans in today’s world and look toward reaching the goal of a truly color-blind society, we must begin with a clear view of the vibrant history of the African-American community and the diversity of African-American experience. When one looks at the images of black America carried around the globe by the miracle of television, it is easy to forget that these powerful images fail to represent the lives of the vast majority of African Americans and consequently who we really are. During my lifetime legal segregation has ended and wide areas of opportunity have opened. In the last twenty-five years, for instance, African Americans gained far greater equal access to education. The result was more equitable opportunities in kindergarten, in elementary school, in junior high and high school that permitted considerably larger numbers of African Americans to earn college degrees. Yet in numerous ways, both large and small, white racism remains to constrict the aspirations of black Americans and cast a shadow on the American dream. The combination of economic and educational deprivation has had devastating consequences for African Americans— consequences that can’t be erased in a few decades. But we have come a mighty long way in the half century since I was born. I can remember having to ride in the back of the bus. I can remember drinking from a “colored” water fountain. But when I recall the past, I marvel at how far we’ve come. Think: in the year I was born, more than 90 percent of all African Americans were living below the poverty line. As this decade began that level was about one-third. But that is still too high, particulary when the national average is less than 15 percent. We still have a long way to go. African Americans make up 10 percent of the workforce—but comprise only 2 percent of the scientists and engineers. African-American seventeen years olds read, on average, at the level of white thirteen year olds. While African-Americans’ scores on the college board exams went up 45 points in the 1980s, the total number earning bachelor’s degrees fell 8 percent. The reason is no mystery. In the 1980s the cost of higher education increased 50 percent, but spending on support of education, at least at the federal level, decreased 50 percent. And African-American families, whose assets average a tenth of that of white families, simply can’t afford to send their children to college without help. Fortunately, the 1990s witnessed new and sustained growth in the black student population. African Americans continued to improve their SAT scores, and the gap between the scores of white students and black students narrowed considerably. In the first half of the 10