Untitled - Hannes Andersson PDF

Preview Untitled - Hannes Andersson

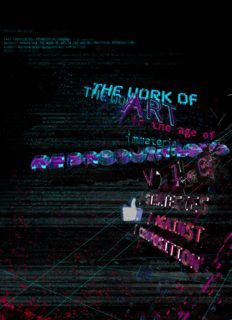

HANNES /ARVID //ANDERSSON Supervisior DRS. L.H.M.P. LEO DELFGAAUW T H E W O R K O F A RT I N T H E A G E O F I M M AT E R I A L R E P R O D U C T I O N S V 1 . 0 / STRATEGIES / AGAINST / COMPOSITION MA MADtech, FRANK MOHR INSTITUTE, MINERVA ART ACADEMY, HANZE UNI- VERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES, GRONINGEN JUNE 2017 2017 Frank Mohr Institute, Groningen This work is licensed under the Creative Commons g n Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International i (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) r a To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- C sa/4.0/. s sharing Andersson, Hannes, 1985- i isn’t THE WORK OF ART IN THE AGE g OF IMMATERIAL REPRODUCTIONS V1.0 immoral n / STRATEGIES / AGAINST i - it’s a r / COMPOSITION a moral Version 1.0 h imperative. S CHIN MEDIA - Aaron Swartz Excerpts from Guerilla Open Access Manifesto by Aaron Swartz The world’s entire scientific and cultural heritage, pub- Large corporations, of course, are blinded by greed. The lished over centuries in books and journals, is increasing- laws under which they operate require it — their share- ly being digitized and locked up by a handful of private holders would revolt at anything less. And the politicians corporations. Want to read the papers featuring the most they have bought off back them, passing laws giving famous results of the sciences? You’ll need to send enor- them the exclusive power to decide who can make cop- mous amounts to publishers like Reed Elsevier. ies. Forcing academics to pay money to read the work of There is no justice in following unjust laws. It’s time to their colleagues? Scanning entire libraries but only allow- come into the light and, in the grand tradition of civil dis- ing the folks at Google to read them? Providing scientific obedience, declare our opposition to this private theft of articles to those at elite universities in the First World, but public culture. not to children in the Global South? It’s outrageous and unacceptable. We need to take information, wherever it is stored, make our copies and share them with the world. We need to Those with access to these resources — students, librar- take stuff that’s out of copyright and add it to the archive. ians, scientists — you have been given a privilege. You We need to buy secret databases and put them on the get to feed at this banquet of knowledge while the rest Web. We need to download scientific journals and upload of the world is locked out. But you need not — indeed, them to file sharing networks. We need to fight for Gueril- morally, you cannot — keep this privilege for yourselves. la Open Access. You have a duty to share it with the world. And you have: trading passwords with colleagues, filling download re- With enough of us, around the world, we’ll not just send a quests for friends. strong message opposing the privatization of knowledge — we’ll make it a thing of the sharing isn’t immoral — it’s a moral imperative. past. Will you join us? those blinded by greed would refuse to let a friend make a copy. - For Rickard Going for that great beyond, Rest in peace my brother Acknowledgements Apart from the obvious mention of my partner Gao Qiwen, who has provided much love, sup- port and food for thought in this process and otherwise, much credit should also be given to Hendrik Hantschel, as idea balling with him is invaluable in -and by now more or less insep- arable from- my artistic process as well as my thinking in general. Also, to Romy Joya Kuldip Singh who (apart from collaborating on various projects) saves me from many steep edges, and has a very inspiring conquer-the-world-kind-of-attitude comparable to that of Genghis Khan (go get them little sister): As well as Lee Mc Donald, with whom I often find myself dis- cussing the ins and outs of reality in the last hours before dawn, and Taiping Xu who never gets even a little bit stressed about anything, which always helps me balance my own. The five of them make up the human contact I have most days, and without them I would probably have gone insane long ago. A special mention should also be given to Norma Deseke, together with whom I conceptual- ized the predecessor to this book, and who greatly have expanded my thinking and provided me with language for expressing it. Most likely, none of the artworks in this book would have materialised without me meeting Anastasia Pistofidou, Ovidiu Cincheza and Marte Roel; Who have a credit list way too long to mention here, but are probably the best production team (and flatmates) that one could possible have; the combined force outclassing almost anyone in everything from digital pro- duction & programming to mountain climbing and music making; Who are, together with the rest of the Chinos - especially Philippe Bertrand, Daniel Gonzales Franco, Tony Higuchi and Jordi Planas (as well as Eva Domènech for whatever its worth) - responsible for getting this whole thing rolling in the first place. The same goes to the other half of Andersson Rodríguez Films: Luis Simón Jose Gregoria De La Santisima Trinidad Núñez Rodríguez [yes, that is actually his name], who is the only person that I have ever met who thinks about cinema in the same way as I do (May you live forever in Jah army and may your hair grow big and fluffy). Special thanks go to my tutors Jan Klug, Ruud Akse for the role they have played in my de- velopment and the skills and support that they have given me, and to Hugo Garcia who made sure I knew what there was to know about the video format before sending me off, as well as to everyone who has contributed in different ways to my process or the making of my works, especially Ioana Bacanu, Jonas Larsson, Richard Fraser, Sander Trispel, Laila Tafur, Oscar Diaz Huerta, Rikke Wahl, Anders Hattne, Kimball Holth, Salim Bayri, Jip De Beer, Simon Haak- meester, Margo Slomp, Guy Wampa Wood, Michiel Koelink, Joachim De Vries, Adrian Papari, Christian Cherene, Alex Dubor, Max Verstrepen, Bruno Barrán, Ariana Cardenas, Saskia Lil- lepuu, Augusto Zuniga, Kuba Markiewicz, Michal Kukucka, Pascal Gielen, Ioana Păun, Lucas Capelli, Tomas Diez, Jerome Villeneuve, Valentina Sutti, Elena Lamberti, Paolo Granata, Iannis Zannos, Kim Sawchuk, Ryan Bishop, Daniela Marques, Bobbo and Rickard Moroso. As well as to my parents who always have supported me. About the Author Hannes Arvid Andersson Audiovisuologist Netherlands Hannes Arvid Andersson (1985) is a Swedish born (later Spanified) audio-visual artist and researcher currently based in the Netherlands. Inspired by artists and thinkers such Chris Salter, TeZ, Kurt Hentchläger, Edward W. Said, Gilles Deleuze and Wil- liam S. Burroughs, he uses critical poetics (po[e]litics) and applied science fiction to explore narrative affect and interrogate the ins and outs of the multiverse. Hannes has studied Media Art & Technology at The Frank Mohr Institute, Academie Minerva (Netherlands) as well as Digital Film Making and Animation at SAE Barcelona (Catalonia). http://handersson.net @handerssonart #poeliticsfromtheanthropocene INTRODUCTION If asked what this book is about I could say that it is about everything. You probably wouldn’t agree, as the topics it is dealing with are far too few are dealt with far too shallowly to encapsulate something as big as ‘everything’. You would probably be right. But then again, my ‘everything’ does not look the same as yours. There might (although I doubt it) be such a thing as an all-encompassing ‘The Everything’, but even so, the book is not about that. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that it is an attempt to share with you how everything looks from here (my thoughts and my perspective); how it came to look like that (my influences and my experience); how I engage with the world in which I find myself (my work and my methods). Blake (2015) stated in his ‘Book of Urizen’, that the only way to grasp infinity is through minute particulars and the wirey bounding line. The world is not made up of anything all-encompassing. But rather of small particular events, actions and observations, and the ways in which they connect to form lines and flows and bigger bodies or “blocks of space-time” as Deleuze describes it. The world is not uniform and it is certainly not fixed. The regularities of life are nothing more than “a temporary barrier island of stability in stormy seas” (Massumi. 2015 p.9). Reality is made in dialogue. It emerges from the in-betweens. And the greatest mistake we could make is to assume that it is no longer open for discussion. As an artist, I am interested in what emerges from the in-betweens, for example in the interplay between factors such as human-nonhuman and digital-physical, and in how the intermediality of the multiverse affect our perception as well as diffuse boundary constructions between real and imaginary. I explore these topics according to a logic of form re- flecting content and this is also how I try to communicate my findings. I have lived most of my life in some sort of an in-between, be that as an interdisciplinary artist; a transnational nomad; a seafaring croupier; a night worker from a lower-class neighbourhood in the process of gentrification or; the son of two divorced psychologists who each pledge allegiance to two very different philosophies of life. The latter is perhaps worth highlighting as this from the very beginning presented me with two distinct versions of reality that, although internally coherent and well argued, always seemed contradictory to each other and hence pro- vided little consistency in regards to making assumptions about how things are and how they are supposed to ‘be’. Considering this it is perhaps logical, that I find myself drawn to the ideas brought forward by thinkers such as: Alfred North Whitehead, Félix Guattari, Gilles Deleuze and Brian Massumi who do not concern themselves so much with ‘things’ as with motions and activities; with ongoings; with ‘things-in-the-making’ as William James famously phrased it. Other influences include the writings on culture and media by Edward W. Said, Marshall McLuhan, Berthold Brecht, John Berger, Alexander Bard, Arjen Mulder, Ryan Bishiop and Rosa Menkmann; The speculative writings of William Burroughs, Oscar Wilde, William Gibson, Karin Boye, Neal Stephenson and Phillip K. Dick; Activivist design practitioners such as Adbusters and Toiletpaper Magazine; and the work of many artist working with various mediums, most notably Chris Salter, TeZ, Kurt Hentshläger, Amnesia Scanner, Bill Kouligas, Harm van den Dorpel, Kyle McDonnald, Julian Oliver, Gaspar Noe, Wong Kar Wai, David Chronenburg and Chris Cunningham, among others. I hope to contribute to this sprawling lineage by conceptualising and examplifying a methodological framework for the form of investigation and communication which I have come to refer to as ‘Po[e]litics’. Po[e]litics can be thought of as a Portable Philosophy Format; a .ppf with variable compression. It is an attempt at constructing a language capable of addressing the complexities of contemporaneity: A trans-medial language appropriate of the anthropocene; A language for the networked human. This is a process-oriented exploration, and as such it does not attempt to end with overview. In fact, it doesn’t attempt to end at all. The aim is to keep on going, and to “arrive at a transformational matrix of concepts apt to continue the open-ended voyage of thinking-feeling (Massumi 2015)”. I will try, dear reader, to explain what I mean by this, and I will do so in the language of po[e]litics, this book being a po[e]litical argument. Before you might understand me, you must know me. I shall hence introduce myself. Part I hello world! This is a story from Gothenburg to Groningen. A travel distance of 929 km, and a ten hour drive according to Google Maps, although I seriously doubt that, having myself never done To answer the first question: that drive in less that than two days. But then My name is Hannes. again, the times that I did drive the Google Hannes Arvid Andersson. way, it was with the Amazon in her Mercedes, which, being made in 1972, was quite frankly not the fastest car (Plus the battery change “Where do is the second question, whenever I meet somebody never seemed urgent enough, and we had a habit you come new. of making detours). from?” Most people I meet are not from where they happen Great car though. to be at the time. It comes after “what is your name?”, but before Very “what do you do?”. Cinematographic. “Where are you from?” is difficult, when you don´t regard the country of birth as your home. But they came later, those True to so many people in my generation. Generation drives with the Mercedes, Y: The first children of the information era, created on the Google way that in a world where everything is possible and nothing is didn’t take ten hours. certain. Enabled as well as obligated to move by the force of political economic circumstances. The first Gothenburg to Groningen is a different This is not without a sense of fragmentation, a sense of kind of story, one that also didn’t take ten hours, not fitting in the categorised national culture one is but rather something like six years. supposed to represent. Where are you from is no longer a question that can be 929 km in six years makes roughly 0,018 km / hour. answered with a single word, with the name of a nation Pretty slow you might think. serving as the agreed upon social and But then again, I did not know the Google way cultural contract. It needs more time and back then, and the way that I found was not that reflection. If we take that time, and listen to the straight. long answer, not only from where they came, but how they got here and what changed in the process, we might learn something about ourselves. “Just as human beings make their own history, they also make their cultures and ethnic identities. No one can deny the persisting continuities of long traditions, sustained habitations, national languages, and cultural geographies, but there seems no reason except fear and prejudice to keep insisting on their separation and distinctiveness, as if that was all human life was about” - Edward W. Said “ Y o u h a v e t o m a k e t h e c h o i c e i n l i f e , b e a g a m b l e r o r a c r o u p i e r a n d t h e n Thus spoke Clive Owen as Jack in the 1998 B movie “Croupier” (Photo). l i v e w i t h y o u r I used to be a croupier. First in Gothenburg, later d e c i s i o n , at sea. 6 years in total. It taught me much about human nature and the c o m e w h a t m a y ” mAlimnods. t ate my soul. The Casino eats many lives - lives from all the sides of that gambling paradigm. Many are the houses sacrificed on the felted table of odds-against-you. The House always wins. House always has the deeper wallet. The House is always hungry. I guess that in the end, I find myself closer to the side of the gamblers. Although I must say, I hold little regard for the gamblers logic; win being well played, loss due to bad luck. That’s how it goes, everybody knows. Loss is to be expected when playing by the rules of a crooked game. Everybody knows that the dice are loaded Everybody rolls with their fingers crossed Everybody knows the war is over Everybody knows the good guys lost Everybody knows the fight was fixed “Be cunning, and full of tricks, The poor stay poor, the rich get rich and your people will never be destroyed” That’s how it goes Everybody knows - Richard Adams, Watership Down Everybody knows that the boat is leaking Everybody knows that the captain lied Everybody got this broken feeling Like their father or their dog just died Everybody talking to their pockets Everybody wants a box of chocolates And a long-stem rose Everybody knows - Leonard Cohen, Everybody Knows Perpetual Motion // From Gothenburg, // With Love ever since I was eight or nine I’ve been standing on the shoreline for all my life I’ve been waiting for something lasting you loose your hunger and you loose your way you get confused and then you fade away ) oh this town w t b kills you when you are young k o o b - Broder Daniel, ‘Shoreline’. d o o These words were written by (Legendary) Swedish indie-pop icon g Hendrik Berggren, who, he too, grew up in the western parts of y t Gothenburg, Sweden, and they provide a suitable entry point to this t e r book, as they manage to quite accurately pinpoint something inherent P ( to this specific corner of the world where I, as it were, happened to start my existence and hence also this journey. From what I can gather, it seems as though Sweden, in the minds of most people, is imagined as something like this: Not that this is entirely inaccurate, per se. It just isn’t the whole truth...

Description: