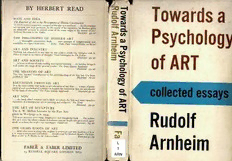

Toward a Psychology of Art: Collected Essays PDF

Preview Toward a Psychology of Art: Collected Essays

BY HERBERT READ Towards a ICON A D IDEA The Function of Art in the Development of Human Consciousness 'A rlnsely written argument, compact of thought and erudition ... the illustrations are unusual and most pertinent. In the cour e of his exposition Sir Herbert gives an admirable accou1it in critical terms of the main stages in the history of art.' Psycho Anthony Bertram in the Tablet. Illustrated 42s net log~ THE PHILOSOPHY OF MODERN ART '. . . a thoroughly provocative book ... with passages of enlightenment and sensibility we expect from him ... .' Apollo Faber Paper Couered Edition 12s 6d net ART A D INDUSTRY ' lothing has appeared in our time on this subject which can compare with it, either in scope or in clarity of thought.' Noel Carrington in The Listener of ART Illustrated 36s net ART AND SOCIETY '. .. it bears evidence of wide reading and careful thinking ... its lucidity brings it well within the range of the general reader.' The Times Litera1y Supj1lement Illustrated 35s net THE MEA ING OF ART 'The best "pocket" introduction to the understanding of art that has ever been published.' Star Illus/rated 18s net EDUCATION THROUGH ART 'It is the most widely read book on art education of our time .. . a mass of philo r,ophical and psychological evidence to support his contention that the arts should be the basis of education.' The Times Literary Suj1plement Illustrated 36s net ART OW '. .. the book which remains and is likely to remain the best and most complete expo ition of contemporary art in painting and sculpture.' The Times • Illustrated 36s net THE ART OF SCULPTURE The A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts given in Wa1hingt:...n in 1954. Rudolf 'This is an intensely interesting, imaginative and thoughtful book ... The author lifts, as it were, the whole volume of sculpture into his hands and presents it, quite small, as a thing the reader can encompass.' Connoisseur Illustrated 84s net THE GRASS ROOTS OF ART -rw '. .. those who want to grasp why reaJism is irrelevant and why modern ::.1t is as it is what it means and symbolizes ... should read Sir Herbert Read's The Grass Roots of Art.' J. P. Hodin in the Lilera7J• Guide. Illustrated 21s net ~ Arnheim L FABER & FABER LIMITED 1 24 RUSSELL SQUARE LOI DON WC1 ARN Rudolf Arnheim TOWA RDS A PSYCHOLOGY OF ART COLLECTED ESSAYS FABER AND FABER 24 Russell Square, London CONTENTS INTRODUCTION I. Keynotes 7 FORl\I AND THE CONSUl\IER 17 AGENDA FOR THE PSYCHOLOGY OF ART II. The Sense of Sight 27 PERCEPTUAL ABSTRACTION AND ART 51 THE GESTALT THEORY OF EXPRESSION 7-f PERCEPTUAL AND AESTHETIC ASPECTS OF THE l\IOVEl\IENT RESPONSE 90 PERCEPTUAL ANALYSIS OF A RORSCHACH CARD 102 A REVIEW OF PROPORTION I II. The Visible World 1 2 3 ORDER AND COMPLEXITY IN LANDSCAPE DESIGN 36 1 THE MYTH OF THE BLEATI G LAMB 51 i ART HISTORY AND THE PARTIAL GOD 62 i ACCIDENT A1 D THE ECESSITY OF ART viii CONTENTS i 81 MELANCHOLY UNSHAPED INTRODUCTION 192 FROM FUNCTION TO EXPRESSION N. Symbols 215 ARTISTIC SYMBOLS-FREUDIAN AND OTHERWISE ·,,,__f\ 222 PERCEPTUAL ANALYSIS OF A SYMBOL OF INTERACTION C)c 245 FOUR ANALYSES: c (. THE HOLES OF HENRY MOORE { A NOTE ON MONSTERS u0 0 PICASSO'S "NIGHTFISHING AT ANTIBES" (' CONCERNING THE DANCE 266 ABSTRACT LANGUAGE AND THE METAPHOR V. Generalities 285 ON INSPIRATION 292 CONTEMPLATION AND CREATIVITY 302 EMOTION AND FEELING IN PSYCHOLOGY AND ART A pyramid of science is under construction. The ambition of the build 3 20 THE ROBIN AND THE SAINT ers is eventually to "cover" all things, mental and physical, human and natural, animate and inanimate, by a few rules. The ramid will look VI. To Teachers and Artists sharp enou h t the eak, but toward the base it will vanish inevitably in a fog of stimulating ignorance like one of those mountains that dissolve 3 37 WHAT KIND OF PSYCHOLOGY? in the emptiness of untouched silk in Chinese brush paintings. For as 343 IS MODERN ART NECESSARY? the base broadens to encompass an ever greater refinement of species, 3 5 3 THE FORM WE SEEK those few sturdy rules will intertwine in endless complexity and form patterns so intricate as to appear untouchable by reason. The prospect is challenging but also frightening. In particular, we may feel tempted to approach the individuality of human nature, human actions, and human creations in an attitude of defeatist awe. To reject all generalization in this field looks good. Who would not like to be the one who respects the ultimate mystery of all things? With the smile of the sage one can, without effort, watch the sacrilegious and clumsy manipulations of the professors. It is an attitude that triumphs in conversation and noncommittal criticism. Unfortunately it gets us no where. Psychology as a humanistic science is beginning to emerge from an uneasy rapprochement between the philosophical and poetical interpre tations of the mind on the one hand and the experimental investigations of muscle, nerve, and gland on the other. And barely are we getting used 2 INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION 3 to what such a science of the mind might be like, when we are faced many overlappings will act as unifying reinforcements rather than as with attempts to deal scientifically with the most delicate, the most in repetitions. tangible, and the most human among the human manifestations. V.le These papers represent much of the output of the quarter of a cen attempt a psychology of art. tury during which I have been privileged to live, study, and teach in the It is a recent example of the many cross-connections that are being United States. To me, they are not so much the steps of a development established, during the construction of the great pyramid, between thus as the gradual spelling-out of a position. For this reason, I have grouped far unrelated disciplines of knowledge. "Psychology of Art" - there is a them systematically, not chronologically. For the same reason, I did not moment of silence during which a person confronted with this notion hesitate to change the words I wrote years ago wherever I thought I for the first time tries hastily to reconcile an approach and a subject could clarify their meaning. Removed from my original intimacy with matter, psychology and art, which do not seem to relate well. 0 yes, at the content, I approached the text as an unprepared reader, and when I second thought there appear some fleeting connotations: Leonardo's vul stumbled, I tried to repair the road. In some instances, I recast whole ture, Beethoven's nephew, Van Gogh's ear. The prospect does not sections, not in order to bring them up to date, but in the hope of saying please the friends of the arts, and it may worry the psychologist. better what I meant at the time. The papers collected in this book are based on the assumption that Some of the earlier papers led to my book, Art and Visual Percep art, as any other activity of the mind, is subject to psychology, accessible tion, which was written in i951 and first published in i954. Sections of to understanding, and needed for any comprehensive survey of mental the articles on perceptual abstraction, on the Gestalt theory of expres functioning. The author believes, furthermore, that the science of psy sion, and on Henry Moore are incorporated in that book. Others con chology is not limited to measurements under controlled laboratory con tinued where the book left off, for instance, the attempts to describe ditions, but must comprise all attempts to obtain generalizations by more explicitly the symbolism conveyed by visual form. The short piece means of facts as thoroughly established and concepts as well defined as on inspiration provided the substance for the introductory chapter on the investigated situation permits. Therefore the psychological findings creativity in my more recent book, Picasso's Guemica. Finally, in re offered or referred to in these papers range all the way from experiments reading the material, I was surprised to find how many passages point to in the perception of shape or observations on the art work of children to what is shaping up as my next task, namely, a presentation of visual broad deliberations on the nature of images or of inspiration and con thinking as the common and necessary way of productive problem solv templation. It is also assumed that every area of general psychology calls ing in any human activity. for applications to art. The study of perception applies to the effects of Ten of the papers in this book were first published in the Journal of shape, color, movement, and expression in the visual arts. Motivation Aesthetics and Art Criticism. To mention this is to express my indebted raises the question of what needs are fulfilled by the production and ness to the only scholarly periodical in the United States devoted to the reception of art. The psychology of the normal and the disturbed person theory of art. In particular, Thomas Munro, its first editor, showed a great ality searches the work of art for manifestations of individual attitudes. trust in the contribution of psychology. He made me feel at home And social psychology relates the artist and his contribution to his fellow among the philosophers, art historians, and literary critics whose lively men. propositions inhabit the hostel he founded and sustained. To him, as A systematic book on the psychology of art would have to survey well as to my friends of the University of California Press, who are now relevant work in all of these areas. My papers undertake nothing of the publishing my fourth book, I wish to say that much of what I thought kind. They are due to one man's outlook and interest, and they report about in these years might not have been cast into final writing, had it on whatever happened to occur to him. They are presented together be not been for their sympathy, which encouraged the novice and keeps a cause they turn out to be concerned with a limited number of common critical eye on the more self-assured pro. themes. Often, but unintentionally, a hint in one paper is expanded to There are a few scientific papers here, originally written for psycholog· full exposition in another, and different applications of one and the ical journals but free, I hope, of the terminological incrustation that same concept are found in different papers. I can only hope that the would hide their meaning from sight. There are essays for the educated 4 INTRODUCTION friend of the arts. And there are speeches, intended to suggest practical I. K01notes consequences for art education, for the concerns of the artist, and for the function of art in our time. These public lectures are hardly the prod ucts of a missionary temperament. In fact, I marveled why anybody would go to a theorist for counsel, illumination, and reassurance in prac tical matters. However, when I responded to such requests I noticed, bewildered and delighted, that some of my findings suggested tangible consequences, and that these consequences were wanted. FORM AND THE CONSU 1ER Art has become incomprehensible. Perhaps nothing so much as this fact distinguishes art today from what it has been at any other place or time. Art has always been used, and thought of, as a means of interpreting the nature of world and life to human eyes and ears; but now the objects of art are apparently among the most puzzling implements man has ever made. Now it is they that need interpretation. Not only are the paintings, the sculpture, and the music of today incomprehensible to many, but even what, according to our experts, we are supposed to find in the art of the past no longer makes sense to the average person. Listen to what happens when one of the best known modem critics, Roger Fry, looks at a painting of the i 7th century: Let us note our impressions as nearly as possible in the order in which they arise. First the curious impression of the receding rectangular hollow of the hall seen in perspective and the lateral spread, in contrast to that, of the cham ber in which the scene takes place. This we see to be almost continuously occupied by the volumes of the figures disposed around the circular table, and these volumes are all ample and clearly distinguished but bound together by contrasted movements of the whole body and also by the flowing rhythm set up by the arms, a rhythm which, as it were, plays over and across the main \'Olumes. Next, I find, the four dark rectangular openings at the end of the hall First published in the College Art fournal, Fall 1959, i9, 2-<). 8 FORM AND THE CONSUMER FORM AND THE CONSUMER 9 impose themselves and are instantly and agreeably related to the two dark Leonardo that this natural gift of form began to suffer a rare disturb masses of the chamber wall to right and left, as well as to various darker masses ance, created by a civilization that was to replace perceiving with meas in the dresses. We note, too, almost at once, that the excessive symmetry of uring, inventing with copying, images with intellectual concepts, and these four openings is broken by the figure of one of the girls, and that this appearances with abstract forces. In the nineteenth century, to be a also somehow fits in with the slight asymmetry of the dark masses of the cham good artist had become much more difficult than it had been for two ber walls ( 3, p. 23). thousand years. And whereas normally one of the hardest tasks for a Now'. this painting, attributed to Nicolas Poussin, tells the story of human being is to make an ugly object, an epidemic of ugliness now in how Achilles was dressed as a girl by his mother Thetis and hid fected everything within the reach of the new civilization. among the daughters of King Lycomedes because she did not want him Therapy often requires radical measures, and it was the instinct of to go to Troy and be killed in the war. In the picture, we plainly see self-preservation that made sensitive critics insensitive to the perversity Odysseus who in the costume of a peddler entertains the girls with his of such sentences as: "Art is the contemplation of formal relations." But wares and traps the disguised Achilles by baiting him with a helmet and that is what was said about painting and sculpture. In a neighboring a shield. field, the remarkable Eduard Hanslick, battling against the notion that No one could possibly miss seeing the six persons in the foreground music existed for the purpose of reproducing the feelings of the human of the picture. Roger Fry saw them too, but he hardly looked at them. mind, maintained instead that the content of music was "tonend He thought the story was boringly told and did not matter. Nor did he bewegte Formen," that is, "sounding forms in motion" ( 5, ch. 2). consider it relevant that the painter Poussin himself "would have been The consequences of such an approach are illustrated in Fry's anal speechless with indignation" at the analysis of what the critic thought ysis of the so-called Poussin. No doubt, it indicates a frightening es the picture was about. trangement of the sensory experiences from their meaning. At the same me summarize wha we have eard so far. A great artist has told time, we must acknowledge the size of the threat to which such formal a story. Th - .' does no at,.ter. The fact that he wanted to tell the ism was and is reacting. The danger shows not so much in the work of story does not matter. The fact that.he is supposed to have told it badly the few great artists who succeed in struggling to the heights, but-to 5locs not matter. His picture is great. It deals with rectangular hollows speak only of painting and sculpture-in the middle-class of insipidly and volumes and contrasted movements and dark openings. At this realistic portraits and landscapes, in the snapshots cast in bronze that e;iint, if your and my senses still WQrk, we feel a cold shiver as though celebrate the memory of famous men in our public squares, in the op touched b the wing of madness. pressive materialism of official Communist art, in the symbolic marble Yet Roger Fry was a very sane man. And equally sane are most of athletes on the fa~ades of our own government buildings, in the shape the men and women who speak and write and teach as he did. But Fry lessness of old-fashioned ornaments and new-fangled "abstract" con was fighting a battle. Art had fallen into the dan(Ter of losing form glomerations of geometry and texture. Man's natural sense of form is mainly by trying to become a mechanically correct 0r eproduction of na-' indeed threatened, and a large-scale reclaiming action is in order. ture. That art should make faithful reproductions had been maintained But it is one thing to pay attention to the damage and quite another in theory for a long time. When Leonardo da Vinci and his colleagues to restrict the concern of art to the elements of sensory phenomena. The talked about their craft, they discussed paints and tools and materials assertion that "art is the contemplation of formal relation(' must be con and hundreds of tricks as to how to represent animate and inanimate fronted here with the fundamental and well-established principle that things in a strictly life-like manner. They had much less to say about "good ,form does not show." what we now call the sense of form, namely, the capacity to furnish visi Let us remember that a well-mannered erson is one whose man ble objects with such properties as clarity, unity, harmony, balance, fit ners ;,,e do not notice; tliat a good perfume is perceived as an aspect of tingness, or relevance; because these virtues exert themselves naturally the ady's own mood and character, not as an odor; that a good tailor or whenever any human being builds a boat, or makes a dress or a clay fig hairdresser fashions the person; that the art of the interior decorator or ure, or beats a rhythm, or sings a tune. But it was precisely in the age of lighting designer has failed when it attracts attention to itself instead of H f -,~ ~~~t t:::.. e. r f""'\ \ ;_rt 'Vf(o i-1 rv---\ J le ~ C"'I'\ I fo...J' I FOR!ll AND THE CONSUMER 11 10 FORM AND THE CONSUMER making the room comfortable, elegant, dignified, cold, warm, or what For what has been said here requires reservations. Form is seen to have you; that the ingredients of a good salad dressing are hard to trace, dissolve into content only when the statement is made to conform to the and that the best musical accompaniment of a stage play or film intensi beholder's way of perceiving things. Exotic manners, for instance, strike fies the forces of the dramatic action without being heard by itself. The us with the strangeness of their formal devices. Foreign music may im music at a funeral, in a church, or in a dance hall cannot serve its pur press us as a display of odd sound-effects. In examining a piece of sculp pose if it is contemplated as a set of formal relations. And it is the fu ture done in an unfamiliar style, we may be unable to get beyond the neral, the religious ceremony, and the carnival dance to which we must shape, which puzzles us or which wc admire as original or as masterfully look for the prototypes of artistic experience, not the museum display of proportioned. Granted that educated \Vesterners have become remote objects and the so-called "aesthetic distance" such display pro capable of overcoming this obstacle to a remarkable extent for almost duces. any style the history of art has brought forward anywhere. Flexibility, Is it not true that the great works of art are notoriously reluctant to however, has its limits. Also we pay for it with an extremely unstable yield their secret to analysis? Many useful and clever things are said sense of form. Having trained ourselves to perceive in any idiom, there is about them, but what precisely creates the greatness in the face of an no set of shapes, arbitrary and wilful as it may be, which wc cannot wel old man in a Rembrandt portrait, the desperate passion of a Beethoven come, but, on the other hand, there is no longer any one idiom into quartet, the perfection of a Greek temple, or the intense freshness of a which we slip completely. Being strangers unto nobody and everybody, passage in Dante's Commedia? If we are admitted to the grace of such we find ourselves concerned with shapes. company, we surrender to the magic and barely remember the question: It seems safe to say that the awareness of style, especially one's own How is it done? The formal devices used are submerged in the state style, is an unusual experience. The invariant attributes of one's own ment, in the effect. Precisely this submergence is one of the prerequisites way of being and of doing things are hardly noticed. One cannot really of the work's greatness. see one's own face in the mirror, because what is always around tends to Good form does not show. tue re resentin a wom ..u -~--.. evade consciousness. Similarly, we cannot see the reflection of our per woman no he hape of a woman,-this holds true for a Roman Venus sonal manner in the objects we make. Robust cultures think of their or a Gothic Madonna, and also for an African wood carving or the re own way as the correct way of making things, and distinguish it from the clining figures of Henry Moore. And, in fact, even the woman is part of inferior efforts of the barbarians. In our midst, a genuine artist is likely the form that disappears in order to leave only the pure visible embodi to feel uneasy about what we call his style, since this aspect of his work ment of meaning or character. If, instead of meaning and character, you is almost invisible to him. Cezanne looking at one of his landscapes is see a human body in the flesh, or if, instead of the human body, you see likely to have seen simply the mountain, which he had attempted to de formal relations, something is wrong with the figure ( i). pict as accurately as he could. If somebody had suggested to him that But where does this leave abstract art or music, which, after all, are surely he had changed nature in order to adapt it to his own style, it is nothing other than shapes, colors, sound, rhythm? Exactly the same likely he would have flown into one of his magnificent rages. principle holds true for them. In a successful piece of abstract art or -But Cezanne's style is only partly shared by the consumers. To music, a pattern of forces transmits its particular blend of calmness and them, the Mont Ste Victoire is one mountain among many others, which tenseness, lightness and heaviness-a complete transubstantiation of have been painted by Hiroshige or by Goya, by Brueghel or by Leo form into meaningful expression. As soon, however, as the red circles or nardo. If the consumers are fortunate, their minds will gain from this the blue bars, the crusts of metal or the carefully daubed areas of noth variety of views a rich, but unified conception of what a mountain can ingness make themselves conspicuous; as soon as, in music, the har be. Otherwise, the mountain will vanish and a parade of styles will re monic progressions of the score or the tremolos of the instruments, the main. The Cezanne landscape becomes an arrangement of post diatonic routine or the atonal irresponsibilities, the grating noises or the Impressionist brushstrokes. Or, to use an example from opera: l\fozart's twelve-tone rows are heard as such, something is wrong with the paint voung lovers no longer sing out their suffering and joy, but utter the ing, the sculpture, the music. Or, indeed, with the consumer. melodies and rhythms of the late Baroque. FORM AND THE CONSUMER 13 12 FORM AND THE CONSUMER times do, they will hold forth on what is good and what is bad, who The eclecticism or, if you wish, the universality of our culture is not imitates whom, and how the performance compares with the Budapest alone in being responsible for our worship of form. There are other, Quartet or with Jean-Louis Barrault, or that the second aria was too fast weighty causes, of which I can mention only one, namely, what I will or that the last act betrays the latent homosexuality of the author. All call our "insignificant living." We neglect the human privilege of under these critical observations are presented with a chilly detachment that standing individual events and objects as reflections of the meaning of makes it perfectly clear that the speaker cannot h~ve been ~n recent life. When we break bread or wash our hands, we are only concerned communion with Beethoven or Shakespeare, Verdi, or Matisse. The with nutrition and hygiene. Our waking life is no longer symbolic. This pose coveted by our young intellectuals is no longer. ~hat of the. stirred philosophical and religious decline produces an opacity of the world of lover of the beautiful but the poker face of the cntic, who smffs and experience that is fatal to art because art relies on the world of experi judges. I cannot but think with gratitude of the Texas businessman ence as the carrier of ideas. When the world is no longer transparent, whose wife showed me the precious Renoirs and Derains and Dufys they when objects are nothing but objects, then shapes, colors, and sounds are had on the walls, only to confess with a sigh of resignation: "But I have nothing but shapes, colors, and sounds, and art becomes a technique for never been able to find a Picasso that does not upset my husband when entertaining the senses. Unconscious symbolism, to which we have been he eats his dinner!" If a man has preserved the sense to know that Pi running for salvation, is much too primitive to shoulder the task by it casso is upsetting, the light may shine again some day in the darkness. self. Everything seems to count except what the work of art is about. A Art is the most powerful reminder that man cannot live by bread friend of mine in the theater department talked with a colleague from alone; but we manage to ignore the message by treating art as a set of out-of-town, who had just initiated a course in playwriting. Yes, he sai~, pleasant stimuli. One of my students told me the other day that she the students were doing well indeed. Some fine dialogue had been writ found herself greatly disturbed when she attended a cheerful beer party ten, and there was increasing conciseness and logical sequence. "Of in the living room of friends who had just acquired a very large repro course," he added, "there is no content!" Such episodes make me wo~ duction of Picasso's Guernica. Undoubtedly the friends, being connois der whether it is not high time for us to remember tha~ where there is seurs, thought of Picasso's outcry against the massacre of innocents as a no content there can be no form. decorative pattern of formal relations. And when I remember being The notion of composition for its own sake, which I illustrated with shown through a very modern home in the hills of Los Angeles where a Fry's analysis of a painting, has its counterpart in the studio practice of high-fidelity performance of Bach's St. Matthew's Passion was used to some of our art departments, art schools, and professional art ;ts. There demonstrate that music could be piped through all the rooms of the is great refinement of technique, but little indication that unles~ the art house, including the laundry and the bathrooms, and also how often I ist has something to say there can be no distinction between nght and have had to suffer from recordings of great music being used as back wrong, no preference for one technique as against another. By n~w, we ground noise for conversation by otherwise well-bred and kindly people, start in kindergarten to overwhelm children with an endless vanety of I cannot but realize that music indeed may lose all depth of meaning materials and tricks, which keep them distracted-distracted from the and be reduced to sounding shapes. only task that counts, namely, the slow and patient and disciplined The formalistic approach to art is a device for fending off the dis search for the one and only form that fits the underlying experience. quieting demands that are art's essence.1 Listen to what the audience To be sure, artists have good reasons for being wary of discussing says after one of those concerts that are advertised by nothing but the the ideas expressed in works of art. Any verbal shortcut threatens to re name of the virtuoso, or in an art gallery, or at the theater during inter place the work in its particular concrete complexity ~nd there~y threat mission. If they talk about what they just saw or heard, as they some- ens to paralyze the artist or blind the beholder. That 1s why artists prefer to deal with technique. But there is a decisive difference between the 1 There are other ways of avoiding the issue. The tradition of discussing the modesty of the artist who talks about paints and chisels while his every subject matter instead of what it expresses survives in the search for clinical thought and move is in pursuit of his deepest vision, and the implied symbols.