Toward a Feminist Ethics of Nonviolence PDF

Preview Toward a Feminist Ethics of Nonviolence

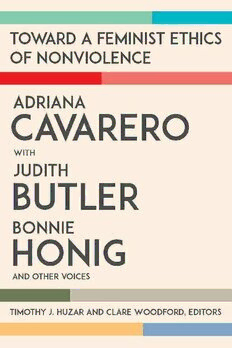

Toward a Feminist Ethics of Nonviolence Toward a Feminist Ethics of Nonviolence Adriana Cavarero, with Judith Butler, Bonnie Honig, and Other Voices Timothy J. Huzar and Clare Woodford, Editors Fordham University Press new york 2021 Copyright © 2021 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other— except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the per sis tence or accuracy of URLs for external or third- party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Visit us online at www . fordhampress . com. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data available online at https:// catalog . loc . gov. Printed in the United States of Amer i ca 23 22 21 5 4 3 2 1 First edition Contents Prelude 1 Timothy J. Huzar Introduction: Adriana Cavarero, Feminisms, and an Ethics of Nonviolence 7 Timothy J. Huzar and Clare Woodford Scenes of Inclination 33 Adriana Cavarero Leaning Out, Caught in the Fall: Interde pen dency and Ethics in Cavarero 46 Judith Butler How to Do Things with Inclination: Antigones, with Cavarero 63 Bonnie Honig Scherzo Thinking Materialistically with Locke, Lonzi, and Cavarero 93 Olivia Guaraldo Études Cavarero, Kant, and the Arcs of Friendship 109 Christine Battersby Bad Inclinations: Cavarero, Queer Theories, and the Drive 121 Lorenzo Bernini vi / Contents Querying Cavarero’s Rectitude 131 Mark Devenney From Horrorism to the Gray Zone 141 Simona Forti Vio lence, Vulnerability, Ontology: Insurrectionary Humanism in Cavarero and Butler 151 Timothy J. Huzar Queer Madonnas: In Love and Friendship 161 Clare Woodford Coda 177 Adriana Cavarero Bibliography 187 List of Contributors 199 Index 203 Toward a Feminist Ethics of Nonviolence Prelude Timothy J. Huzar I met Adriana Cavarero halfway up a mountain in Sicily. P eople from across Eu rope had convened to talk about life, politics, and contingency; Cavarero, as a po liti cal phi los o pher and the foremost Italian feminist scholar writing t oday, was among a number of keynote speakers asked to contribute their thoughts.1 As a student of the relationship between vio- lence and politics I was aware of Cavarero’s Horrorism: Naming Con temporary Vio lence; however, I hadn’t encountered the rest of her oeuvre, and the book, in isolation, had been swept up in a large number of texts I was reading in the early stages of my Ph.D.2 Cavarero’s talk was in Ital- ian, and having no Italian, I was left with the sonority of her voice and her embodied communication; Cavarero at times sitting behind her desk, at times standing and leaning in to the audience, her paper discarded as her oration carried her into the room, focusing in on the interventions from t hose who contributed their thoughts, provocations, and disagree- ments. In between the talks p eople would gather in the courtyard to smoke and drink coffee or beer, sheltering u nder the shade of a grafted citrus tree from the relentless midsummer Sicilian sun. I spoke to Gianmaria Colpani and other students of Cavarero’s about my thesis, and they in- troduced me to some of the key themes that can be found across her work: not only the extrapolation and exploration of horrorist vio lence, but a pro- longed engagement with vocality, feminist materiality, narration, and, above all, Hannah Arendt’s category of uniqueness.3 It became clear that there was a glaring gap in my research, perhaps accounted for by the sway of the biopo liti cal tradition in Italian po liti cal philosophy that Cavarero sits in proximity to, yet apart from. Toward the end of the first eve ning 2 / Timothy J. Huzar Cavarero and I spoke briefly, but it wasn’t u ntil the second eve ning, when enough time had passed for p eople to get to know one another and to re- lax some of the unspoken proprieties that lie just below the surface of the social world of academia, that a sense of who Adriana Cavarero was became more apparent. One of the many themes that can be found in Cavarero’s work is an insistence on a re spect for the palpable truthfulness of the everyday: that in p eople’s everyday experiences something of the world is revealed to them, just as they continuously reveal themselves to the world. This means that despite her classical training and her sophisticated and extensive en- gagements with some of the major debates in twentieth- century conti- nental philosophy, Cavarero’s work insists that meaning is not to be sought in the rarified conceptual worlds of g reat thinkers, but is pre sent in the ordinary world for anyone to see or hear if they only knew how to see or hear it. Her work gives us the tools to make t hese sensory adjustments: each of her books functions something like an eyeglass or a hearing aid that we can use to help learn what it is to see meaning in the everyday and unlearn the compulsive turning to those tropes dear to the Western tradition that are now wearing thin. During the eve ning of the second day of the summer school, Cava- rero demonstrated that her skill at manifesting the meaning pre sent in the everyday was not restricted to her academic work. As the sun set and people drank and smoked, Cavarero suggested that song might be a good tonic for the heady metaphysics that were given form in the reasoned dia- logue of that day’s talks and discussions.4 With the help of Adriana’s enthusiasm, as well as the limoncello and grappa that began to flow at the bar, p eople stood or sat in the now star- lit courtyard, voices raised in song reverberating around the centuries- old stone walls. Some of these songs were known by all, and so the soloist quickly became a member of the chorus, while others began as solo and were slowly joined by other people as they e ither learned the patterns, remembered the words, or clapped to the rhythms. Other songs w ere known only to the singer and so stayed as a singular voice. Yet even here, this was a singularity destined for the ear of another, or in this case many others; and the sociality that was con- voked in this space—or what Cavarero would now call the pluriphony— was palpable to all those pre sent.5 Cavarero, for her part, performed an operatic duet from Mozart’s Don Giovanni— “Là ci darem la mano”— embodying both masculine and feminine parts and, in the pro cess, pro- viding further evidence for Lorenzo Bernini’s intimation in this collection that her reticence regarding Judith Butler’s notion of gender performa- tivity is itself something of a per for mance.6 Prelude / 3 In the months a fter the conference I read all of Cavarero’s work, and her thought profoundly shifted the direction of my thesis. As well as be- ing inspired by her thematic foci, I found validation in her inter- and transdisciplinarity: it was clear that for Cavarero, responding to the ma- jor questions of twentieth- century continental philosophy required an- swers that did not discriminate when it came to the form or content from which they took their resources. As well as some of the major theoretical debates of the twentieth century, Cavarero also engages classical Greek texts, con temporary lit er a ture, Eu ro pean visual arts, and con temporary feminist politics. Each of these bodies of thought helps her articulate a philosophy that is anti- metaphysical, mounting a relentless critique of the presumptively masculine subject of the Western tradition; she demon- strates the absurdity of this figure, juxtaposing him to the singular lives of those who live in the plurality of the world. However, Cavarero is not content with critique alone. More impor tant for her is the articulation of other forms of life— other ways of being or modes of existence— that are systematically overlooked by the gaze of the Western philosophical tra- dition. For Cavarero, while it is necessary to develop a critique of this tra- dition, including the subject fabricated by this tradition, the politics of this intervention falls short if this subject’s deconstruction becomes the telos of this work.7 For Cavarero, then, it is necessary to name the forms of life that she sees as existing despite this presumptively masculine sub- ject, a naming that derives from the lived experience of those whose ex- istence does not conform to his morphology or onto- epistemology. This means her interventions are necessarily identitarian but are also left pro- ductively open, encouraging others to pick up her concepts and make use of them, causing trou ble in the archives of the canon of Western thought and articulating a diff er ent tradition, hidden in plain sight. Over the next year I had the opportunity to pre sent work to Cavarero and her colleagues in Verona, and her colleagues and students presented work at Brighton where I was studying. At vari ous conferences I attended, Cavarero’s name was frequently mentioned by p eople presenting work from a variety of disciplines. It seemed strange that, given her extensive and diverse influence, an event dedicated to her thought hadn’t happened, at least in the English- speaking world. A group of us, including her col- leagues Olivia Guaraldo and Lorenzo Bernini and Mark Devenney and Clare Woodford at Brighton, proposed organ izing an international con- ference on Cavarero’s work, to be titled, “Giving Life to Politics.” The event would coincide with the English- language publication of Cavarero’s In clinations: A Critique of Rectitude, as well as marking Adriana’s seven- tieth birthday.8 Judith Butler and Bonnie Honig— both long- term