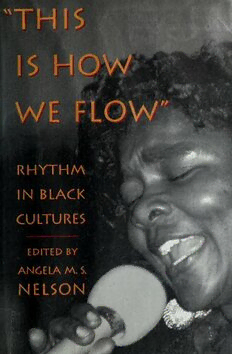

Table Of Content“THIS IS HOW WE FLOW"

RHYTHM IN BLACK Ci!L TURES

EDITED BY ANGELA M. $. NELSON

“This Is How We Flow” explores the meaning, motif,

and theme of rhythm in black cultures throughout

the United States and Africa. In ten pathbreaking

essays the volume’ contributors illustrate how

rhythm is the foundation of all African expression—

from music and dance to the visual arts, architec-

ture, theater, literature, and film. They suggest, by

example, that an African aesthetic does indeed

exist, an aesthetic that revolves around the motif of

rhythm.

In essays that focus on the medium most com-

monly associated with the motif, Juliette Bowles dis-

cusses rhythm’s place in African American music,

and Mark Sumner Harvey examines its conceptual-

ization in jazz music. William C. Banfield suggests a

methodological framework for composing black —

music, and Angela M. S. Nelson identifies the pri-

macy of rhythm in African American rap music.

From Martin Luther King’s speeches to Claude

McKay’ poetry, the contributors also consider

rhythm as a quality in black oratory, literature, and

film. Richard Lischer offers a detailed analysis of

Kings speeches, Ronald Dorris elucidates rhythm’s

meaning in McKays poem “Harlem Dancer,” and

Darren J. N. Middleton considers the power of

rhythm to move people to write and act for social

Justice, as in the poetry of Rastafarian dub poets.

Suggesting that it is through the lens of rhythm that

the meaning of black film of the 1980s and 1990s

becomes clearest, D. Sonyini Madison exposes

rhythm as ritual, modality, and discourse in the film

Daughters of the Dust.

Two contributors round out the discussion by

examining expressions of rhythm in African coun-

tries. Alton B. Pollard III provides a historical-criti-

cal survey of freedom songs in South Africa from the

nineteenth century through the 1990s, and Zeric

Kay Smith examines “macro- and micro-rhyvthms”

in Malian politics, lending credit to the contributors?

collective conviction that rhythm cirganixes snd

frames African behavior regardless of «:ontxt,

* THIS

IS HOW

WE FLOW"

* THIS

IS HOW

WE FLOW

RHYTHM IN

BLACK CULTURES

Edited by

ANGELA M. $. NELSON

abs

University of South Carolina Press

© 1999 University of South Carolina

Published in Columbia, South Carolina, by. the

University of South Carolina Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

03 02 010099 54321

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

This is how we flow : rhythm in Black cultures / edited by Angela M. S. Nelson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 1-57003-190-8

1. Afro-Americans. 2. Blacks. 3. Rhythm. 4. American literature—Afro-American

authors—History and criticism. 5. Afro-American aesthetics. 6. Aesthetics, Black.

7. Afro-American arts. 8. Arts, Black. I. Nelson, Angela M. S., 1964—-

E185 .T45 1999

305.896'073—dc21 98-40207

Permission to reprint current copyrighted material quoted in this volume is gratefully

acknowledged: Chapter 6 is from The Preacher King: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Word That

Moved America by Richard Lischer. Copyright © 1989, Oxford University Press, Inc. Used by

permission of Oxford University Press, Inc. T. J. Anderson, Variations on a Theme by M. B. Tolson.

Copyright © 1969 by T. J. Anderson. Extract reproduced by permission of T. J. Anderson.

William C. Banfield, Spiritual Songs for Tenor and Cello. Extract reproduced by permission of

William C. Banfield. “Can’t Keep a Good Dread Down,” “Dread Eyesight,” “Dread John

Counsel,” and “Ganga Rock” by Benjamin Zephaniah. Copyright © 1985 by Benjamin

Zephaniah. Extract reproduced by permission of Benjamin Zephaniah. “Come Into My House”

by Dana Owens and Mark James. Copyright © 1989 by T-Boy Music Publishing, Inc /Queen

Latifah Music/45 King Music. Used by permission. All rights reserved. “Harlem Dancer” by

Claude McKay. Used by permission of The Archives of Claude McKay, Carl Cowl,

Administrator. “Yoke the Joker” by V. Brown, A. Criss, and K. Gist. Copyright © 1991 by T-Boy

Music Publishing, Inc./Naughty Music. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations / vii

Acknowledgments / ix

Introduction / 1]

CHAPTER ONE

A Rap on Rhythm / 5

Juliette Bowles

CHAPTER TWO

Jazz Time and Our Time: A View from the Outside In / 15

Mark Sumner Harvey

CHAPTER THREE

Some Aesthetic Suggestions for a Working Theory

of the “Undeniable Groove”: How Do We Speak

about Black Rhythm, Setting Text, and Composition? / 32

William C. Banfield

CHAPTER FOUR

Rhythm and Rhyme in Rap / 46

Angela M. S. Nelson

CHAPTER FIVE

The Music of Martin Luther King, Jr. / 54

Richard Lischer

CHAPTER SIX

Rhythm in Claude McKay's “Harlem Dancer” / 63

Ronald Dorris

CHAPTER SEVEN

Chanting Down Babylon: Three Rastafarian Dub Poets / 74

Darren J. N. Middleton

CHAPTER EIGHT

Rhythm as Modality and Discourse in Daughters of the Dust / 87

D. Soyini Madison

vl CONTENTS

CHAPTER NINE

Rhythms of Resistance: The Role of Freedom Song in South Africa / 98

Alton B. Pollard III

CHAPTER TEN

The Rhythm of Everyday Politics: Public Performance and Political Transitions

in Mali / 125

Zeric Kay Smith

Notes / 137

Selected Bibliography / 151

Notes on Contributors / 153

Index / 157