Thinking allegory otherwise PDF

Preview Thinking allegory otherwise

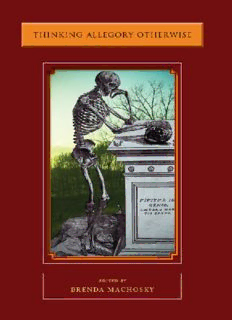

Thinking Allegory Otherwise Thinking Allegory Otherwise Edited by Brenda Machosky stanford university press stanford, california Stanford University Press Stanford, California © 2010 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. This book has been published with the assistance of The Stanford Fund, The Office of the Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education, and The School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University. Essay One was originally published in boundary2, volume 3, no. 1 (Spring). Copyright, Duke University Press. Reprinted with permission. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Thinking allegory otherwise / edited by Brenda Machosky. p. cm. Originates from a conference held at Stanford University in February 2005. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8047-6380-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Allegory—Congresses. I. Machosky, Brenda. PN56.A5T49 2010 809'.915—dc22 2009028684 Typeset by Thompson Type in 11/14 Adobe Garamond. Contents Acknowledgments vii Contributors ix Introduction 1 “A Protean Device” brenda machosky 1. Allegory without Ideas 9 angus j. s. fletcher part one performing allegory 2. Memories and Allegories of the Death Penalty 37 Back to the Medieval Future? jody enders 3. The Mask of Copernicus and the Mark of the Compass 60 Bruno, Galileo, and the Ontology of the Page daniel selcer 4. The Function of Allegory in Baroque Tragic Drama 87 What Benjamin Got Wrong blair hoxby part two allegory in place 5. Colonial Allegories in Paris 119 The Ideology of Primitive Art gordon teskey 6. Monuments and Space as Allegory 142 Town Planning Proposals in Eighteenth-Century Paris richard wittman vi contents part three revisiting allegory in the renaissance 7. Allegory and Female Agency 163 maureen quilligan 8. What Knights Really Want 188 stephen orgel 9. Eliding Absence and Regaining Presence 208 The Materialist Allegory of Good and Evil in Bacon’s Fables and Milton’s Epic catherine gimelli martin part four new dimensions for allegory 10. On Vitality, Figurality, and Orality in Hannah Arendt 237 karen feldman 11. Allegory and Science 249 From Euclid to the Search for Fundamental Structures in Modern Physics james j. paxson Index 265 Acknowledgments A collection such as this depends on the good will of many people and the generous support of many others. This collection is the sequel to a con- ference of the same name. Stanford University President John Hennessy provided financial support for the conference and this publication through The Stanford Fund. Generous funding was also provided by John Bravman, Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education, and Arnold Rampersad, Cog- nizant Dean of the Humanities. In the Office of the President, I would like to thank Jeffrey Wachtel, Senior Assistant to the President, for his support of this project. The Stanford Humanities Center, then under the direction of John Bender, provided an intellectually pleasant atmosphere for the orig- inal conference. My colleagues, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht and Robert Har- rison, encouraged this project and helped bring it to fruition. At Stanford University, this project has also received support from the Division of Lit- eratures, Cultures, and Languages; the Departments of French and Italian, Comparative Literature, and English; The Philosophical Reading Group; The Program in Continuing Studies; The Introduction to the Humanities Program; and Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities. The conference and this book would not have proceeded so smoothly without the help of Monica Moore, Ruth Kaplan, and Ryan Zurowski. Thanks also to the re- viewers, including Bruce T. Clarke, who provided insightful comments on the final organization and production of this collection. I am particularly grateful to Norris Pope and the editorial staff at Stanford University Press, who have provided kind and helpful guidance through this process. I owe especial thanks to the contributors of the volume. These scholars have made my editing job easy and pleasant. I appreciate their patience with me, their enthusiasm for this work, and their continued commitment to thinking allegory otherwise. Contributors jody ender s is a past editor of Theatre Survey and is the author of numerous articles and four books on the interplay of rhetoric, literature, performance theory, law, and the theatrical culture of the European Middle Ages, among them Death by Drama and Other Medieval Urban Legends (Chicago, 2002, and winner of the Barnard Hewitt Award) and Murder by Accident: Medieval Theater, Modern Media, Critical Intentions (Chicago, 2009). She is Professor of French and Theater at the University of Califor- nia, Santa Barbara. a ngus fl etcher is Distinguished Professor Emeritus, CUNY Graduate School. Author of several books and articles on literary theory and history, he published A New Theory for American Poetry: Democracy, Environment, and the Future of Imagination (Harvard, 2004), which won the Truman Capote Prize. In 2007, Harvard published his book, Time, Space and Motion in the Age of Shakespeare. In 2008, he served as J. Paul Getty Research Professor, Los Angeles. Currently he is finishing a book on change and complexity as these occur in the arts and sciences, particularly focusing on the works of Joseph Conrad, Thomas Mann, Karel Capek, and J. G. Ballard. bl a ir hox by, Associate Professor of English at Stanford University, is the author of Mammon’s Music: Literature and Economics in the Age of Milton (Yale, 2002). His recent research has focused on early modern trag- edy, opera, and allegorical drama. His forthcoming Spectacles of the Gods: Tragedy and Tragic Opera, 1550–1780 reconstructs a set of deep assumptions and performance practices that cross national boundaries and makes the early modern period a distinct and meaningful time-section in the history of theater.

Description: