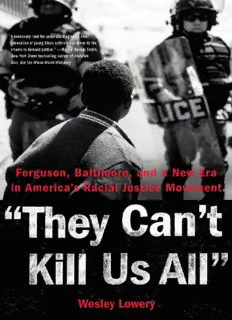

They Can’t Kill Us All: Ferguson, Baltimore, and a New Era in America’s Racial Justice Movement PDF

Preview They Can’t Kill Us All: Ferguson, Baltimore, and a New Era in America’s Racial Justice Movement

Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Introduction THE STORY Chapter One FERGUSON: A CITY HOLDS ITS BREATH Chapter Two CLEVELAND: COMING HOME Chapter Three NORTH CHARLESTON: CAUGHT ON CAMERA Chapter Four BALTIMORE: LIFE PRE-INDICTMENT Chapter Five CHARLESTON: BLACK DEATH IS BLACK DEATH Chapter Six FERGUSON, AGAIN: A YEAR LATER, THE PROTESTS CONTINUE Afterword THREE DAYS IN JULY Acknowledgments About the Author Notes Newsletters Copyright For Jance, Ty, and Feeney, from a boy they helped grow into a man INTRODUCTION The Story O kay, let’s take him.” Within seconds two officers grabbed me, each seizing an arm, and shoved me against the soda dispenser that rested along the front wall of the McDonald’s where I had been eating and working. As I released my clenched hands, my cell phone and notebook fell to the tiled floor. Then came the sharp sting of the plastic zip tie as it was sealed around my hands, pinching tight at the corners of my wrists. I’d never been arrested before, and this wasn’t quite how I’d imagined it would go down. Two days earlier I’d been sent to Ferguson, Missouri, to cover the aftermath of the police shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed black eighteen-year-old. The fatal gunshots, fired by a white police officer, Darren Wilson, were followed by bursts of anger, in the form of both protests and riots. Hundreds, and then thousands, of local residents had flooded the streets. They demanded answers. They demanded justice. In the first forty-eight hours on the ground I filled a notebook: the soft words uttered through thick tears by Lezley McSpadden, Brown’s mother, as she stood for the family’s first press conference since “Mike Mike’s” death; scenes of destruction, including the burned-down QuikTrip gas station and the rows of storefronts that now had thin wooden slabs nailed atop smashed-out windows; scribbles I’d managed while tucked in the back corner of the overflowing sanctuary of Greater St. Mark’s as the Reverend Al Sharpton led an impassioned call and response: “No justice, no peace!”; and the green and brown stains along the corner of my notebook from the moment I was mercifully tackled to the ground, my first night in Ferguson, by a homeowner I was interviewing—a tear gas canister had landed next to us while we spoke on his lawn. There are few things as exhilarating as parachuting into an unknown place with a bag full of pens and notebooks in pursuit of “the story.” And when the phone calls, and coffee meetings, and frantic scribbling are through, piecing it all together. But Ferguson was different because during the early days it was deeply unclear what, exactly, “the story” was. Whatever it was, I now—my arms tugged back behind my back—had become a part of it. I wasn’t happy about it. More than 150 people were taken into custody by the Ferguson and St. Louis County police departments in the week and a half that followed Mike Brown’s death on August 9, 2014—the vast majority for “failure to disperse” charges that came as part of acts of peaceful protest. I was the first journalist to end up in cuffs while covering the unrest. That claim soon became a bit of a technicality, not unlike the twin sibling who declares him-or herself “older.” By the time I had been led out of the restaurant and into the bright sunlight still shining down on St. Louis early that evening, another reporter, the Huffington Post’s Ryan Reilly, whom I had met for the first time earlier that day, was also being led out of the restaurant, shouting that the officers had just slammed his head into the door on the way out. For the Ferguson press corps—which would eventually swell from dozens of daily reporters for local St. Louis outlets and regional reporters for national shops into hundreds of journalists, including ones from dozens of foreign countries—the McDonald’s on West Florissant Avenue became the newsroom. Not that we all had much choice in the matter; the modest-sized dining room with a single television on the wall and movie rental box in the back corner was the only spot within walking distance of the street where Mike Brown had been killed that had all three of the essentials required by a reporter on the road: bathrooms, Wi-Fi, and electrical outlets. Because the protests were largely, in those first days, organic and not called by any specific group or set of activists, they were also unpredictable. Some of the demonstrators came to demand an immediate indictment of the officer. Others wanted officials to explain what had happened that day, to tell them who this officer was and why this young man was dead. Scores more stood on sidewalks and street corners unable to articulate their exact demands—they just knew they wanted justice. Covering Ferguson directly after the killing of Mike Brown involved hours on the streets, with clusters of reporters staked out from the early afternoon into the early hours of the morning. At any point a resident or a group of them could begin a heated argument with the police or a reporter. A demonstration that had for hours consisted of a group of local women standing and chanting on a street corner would suddenly evolve into a chain of bodies blocking traffic, or an impromptu march to the other side of town. And as the summer sun gave way to night, the prospect of violence—both the bricks and bottles of a would-be rioter and the batons and rubber bullets of local police officers—increased exponentially. As long as the protesters and the police remained on the streets, reporters had to as well. Not since the Boston Marathon bombings a year and a half earlier had I covered a story for which there was such intense, immediate appetite. Earlier on the day I was arrested, I tweeted digital video and photo updates from the spot where Brown had been shot and killed, from the burned-out shell of the QuikTrip gas station torched in the first night of rioting, of the peaceful crowds of church ladies who gathered that afternoon on West Florissant—a major thoroughfare not far from where the shooting occurred that played host to most of the demonstrations—as well as the heavily armored police vehicles that responded to monitor them. For years, updates like these would have been phoned into the newsroom, with a reporter describing the unfolding situation sentence by sentence as a rewrite guy molded the news into already existing articles. Now they could be published instantaneously. But an iPhone battery only lasts for so long, so with the deadline for the story I was writing for tomorrow’s newspaper looming, I left the protest and made the three-block trek to the McDonald’s, bought a Big Mac and fries, from across the room greeted Ryan, and holed up in the corner of the dining room to let my phone charge. It wasn’t long later when the riot-gear-clad officers entered, suggesting we all leave because, with protests still simmering outside, things could get dangerous once the sun went down. Then, when it became clear that we were happy to wait and see how things developed outside, they changed their tune. Now the officers were demanding we leave. I was annoyed, but covering protests and demonstrations often means taking direction that doesn’t make sense from police officers who aren’t quite concerned with your convenience, much less your ability to do your job. I kept my phone, which was recording video, propped up in one hand as I shoved my notebooks into the same fading green backpack I’ve carried since my senior year of high school. As I packed, I attempted to ask the officer now standing in my face if I’d be able to move my rental car from the parking lot. He didn’t, he said, have time for questions. Once I’d finished packing, I walked past him, making my way toward the door. As I walked to the exit, the officers decided that all this had taken too long. It had been about one minute since they had first told me to leave when I heard one officer say, “Okay, let’s take him,” and then felt their arms grab me from behind. Now I stood on my tiptoes, insisting to Officer Friendly that I was, in fact, complying with his demands even though he was insisting that I wasn’t. “My hands are behind my back!” I shouted to the uniformed men now pressing their weight into me as they ran their gloved hands down my front and back pants pockets, which contained an abundance of pens and exactly zero weapons. “No, you’re resisting, stop resisting,” an officer barked back at me, before I was led out of the building. On August 9, 2014, the Saturday when six bullets fired by Darren Wilson entered Mike Brown’s body, I was sailing in Boston Harbor with two of my former Boston Globe colleagues. Seated snugly in a small sailboat settled out deep in the water, we stared up at the city skyline drifting farther from us and the planes coming into Logan Airport descending low over our heads. This was one of what had been half a dozen return trips to Boston in the seven months since I’d left a job as a metro reporter for the Globe, my first full- time reporting gig after college, to join the staff of the Washington Post. For the year or so that I had worked in Boston, I wrote breaking news for the metro desk and chipped in on the political desk, covering crime scenes and campaigns, police tape and ticker tape. One day, I’d be in the backseat of an SUV listening to a mayoral candidate coax money out of the pockets of donors as underpaid and overcaffeinated staff members tried to run damage control. (“Everything said in the car can be off the record, right?”) The next day I’d get an early-morning call from Mike Bello, the Globe’s deputy city editor and a hard-charging, no-nonsense assignment editor who was among the favorites of my many bosses. “Mornin’, pal,” he’d say in low, growling yet friendly Bostonian. “Did I wake you?” “Of course not. I was just getting ready to come into the office,” I’d always reply.

Description: