The Wines of Greece PDF

Preview The Wines of Greece

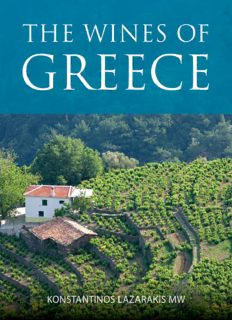

THE INFINITE IDEAS CLASSIC WINE LIBRARY Editorial board: Sarah Jane Evans MW and Richard Mayson There is something uniquely satisfying about a good wine book, preferably read with a glass of the said wine in hand. The Infinite Ideas Classic Wine Library is a series of wine books written by authors who are both knowledgeable and passionate about their subject. Each title in The Infinite Ideas Classic Wine Library covers a wine region, country or type and together the books are designed to form a comprehensive guide to the world of wine as well as an enjoyable read, appealing to wine professionals, wine lovers, tourists, armchair travellers and wine trade students alike. Port and the Douro, Richard Mayson Cognac: The story of the world’s greatest brandy, Nicholas Faith Sherry, Julian Jeffs Madeira: The islands and their wines, Richard Mayson The wines of Austria, Stephen Brook Biodynamic wine, Monty Waldin The story of champagne, Nicholas Faith The wines of Faugères, Rosemary George MW Côte d’Or: The wines and winemakers of the heart of Burgundy, Raymond Blake The wines of Canada, Rod Phillips Rosé: Understanding the pink wine revolution, Elizabeth Gabay MW Amarone and the fine wines of Verona, Michael Garner The wines of Greece, Konstantinos Lazarakis MW Konstantinos Lazarakis MW became the first Greek Master of Wine in 2002 at the age of 32. He is a member of the Board of Directors of the Institute of Masters of Wine (IMW) and Chairman of the IMW Trips Committee. In 2004 he co-founded Wine & Spirits Professional Center, an educational organization that runs Wine & Spirits Education Trust and Court of Master Sommeliers courses throughout Greece. Konstantinos is Imports Director for Aiolos Wines and consults widely for Enterprise Greece, Aegean Airlines and several other businesses. He also writes for a number of trade and lifestyle magazines and is President of the Balkan International Wine Competition as well as President of the Thessaloniki International Wine and Spirit Competition. CONTENTS Acknowledgements Preface to the first edition Introduction Part 1: The background 1. The history of Greek wine 2. A new era beckons 3. The Greek landscape 4. The Grapes Part 2: The regions 5. Thrace 6. Macedonia 7. Epirus 8. Thessaly 9. Central Greece 10. The Ionian islands 11. The Peloponnese 12. The Cyclades 13. The Dodecanese 14. The North Aegean islands 15. Crete Epilogue Appendix I – Wine legislation and labels Appendix II – Native Greek varieties Glossary Bibliography and resources Index ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have been saying, publicly and repeatedly, that I would never write a second edition of The wines of Greece. It was Richard Mayson, on a bitterly cold morning and over coffee at the Institute of Directors in London, who made me change my mind. Now that I am finished, I feel that I should thank him first. Richard Burton and Rebecca Clare from Infinite Ideas made this book possible. Nothing that could be written here could fully express my gratitude. This book would also not have been possible without the precious help of numerous other people. Any attempt to put on paper all those that helped me acquire stamina, information, facts and figures is bound to fail. I am sure that everyone who belongs to that group knows it – and saying ‘Thank you’ is simply not enough. A special mention however has to go to Stavroula Georgopoulou and Thomas Glezakos, from the Directorate of E-Governance of the Ministry of Rural Development and Food, for passing on to me invaluable statistics. Also, to eagle-eyed Nikos Panidis, my fabulous assistant, who made the writing process so much easier and more enjoyable for me. I wish I had had you on board back in 2005! This book is for Yiannis Tripkos, Alexandros Tselepidis and Giorgos Tripkos, for their endless support, even before they know what I am up to. They showed me how to flourish. It is also for my family, Antonia and Anastassios. They never question how I handle possibly the only precious thing I can give them: Time. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION It is very difficult for a book about the wines of any one country to be both good and totally impartial. To be good, it should be written by someone with a deep understanding of the subject. An outsider will have an independent point of view but, at the same time, might have problems appreciating where the country and its people come from, why and where they are heading. Wine is not a still life or a photograph – it is dynamic. The more you become involved with any subject, the more your background, personal tastes and experiences are bound to be influential, if only at a subconscious level. Therefore impartiality is out of the window, even if the writer goes to great lengths to prevent this. But is impartiality really needed in a book like this? It is certainly required in matters of judgement, where comparing and finding the best necessitates a well- defined decision-making process and a set of exact criteria. Many wine books include all different kinds of star ratings and scores as a guide for readers. Guidance is needed for a complex topic like wine and the majority of wine- drinkers cannot spend significant amounts of time or money getting acquainted with the huge range of wines from around the world. Even so, with such guides there is an underlying risk that individual tastes can become substituted for a collective one – that of the most influential critic. Exchanging personal opinion for a ready-made assurance is an easy but dangerous way to negotiate the intricacies of wine. In addition, it is too tempting for someone to pick up a glass – especially if they are in the wrong frame of mind, having a bad day or pre- judging the wine – and say ‘this is a bad wine’. In my opinion it is not fair to judge a wine by giving it a window of opportunity of less than a minute, three sniffs and two sips. Beyond such matters of personal taste, people brought up in traditional wine- producing regions find it extremely hard to judge wine based only on what it is in the glass. In countries like Greece, wine has a social dimension that must be taken into account. Agriculture is, most of the time and for most people, a decent kind of poverty. Behind every artisan wine is an immense amount of effort, which has been applied in the hope of creating something worthwhile. Most producers try to make the best they can, according to their preferences, culture, and education. Such attempts are not a part of a marketing strategy but a matter of survival, of struggling for a better future, either for oneself or one’s family. It can be argued that these ‘behind the scenes’ factors do not concern the average punter and that what is important is how the wine in the glass meets the expectations of the final customer. However, many wine-lovers do have a respect for the people that make a living out of wine-growing. They appreciate that there is more at stake than a small tasting note in a book or magazine: ‘The fruit is not complex, the finish is a bit dry, and it scores seventy-five points out of 100’. Therefore, this is not a book about ratings. It is about a country’s visions and disillusions, dreams and traumas, problems and solutions, defeats and triumphs. And since day one, Greeks have always had a most wonderful way of dealing with these. Piraeus, Saturday 11 June 2005 INTRODUCTION Greek wine in the global wine scene is, to use a Greek word, an oxymoron. It is one of the oldest wine-producing countries in the world. It is the place where the first sought after wines were made, and made famous. The concept of grands crus and the cult wines of today stems from ancient Greece. The Greeks have one of the deepest wine cultures in the world. In more than one way, Greeks paved the way for wine to become a fascinating, aspirational product. Greek wine has been through a sea of transformation over the last century, with the rate of change becoming breathtaking since the 1980s. Greek wine producers are actually a very interesting breed. Their approach combines elements from the New World as well as their Old World counterparts. They work with some of the oldest grape varieties on the planet, yet they expend tremendous amounts of effort realizing the potential of their vines, their vineyards and even themselves. Developments in production went hand in hand with developments in the Greek consumer base. Greek wine drinkers who, for better or for worse, are the main customers of Greek wineries, provided the ideal template of challenges for national winemakers. Younger generations had to be convinced that wine- drinking could be cool. Older generations had to be converted to bottled (as opposed to bulk) wine. Both had to be taught that wine can be an aspirational part of everyday life. Many wine consumers, once they turned into wine lovers, realized that there is a lot more to discover in wines made in other countries, keeping Greek winemakers on their toes. This perfect example of social– agricultural co-evolution in itself makes Greek wine very interesting. I often see old friends at wine fairs in France, the UK or the US. Even today, when I invite them over to the Greek stands to taste some wine I frequently get the one-line response, ‘I do not like retsina,’ as an answer. And it is wine professionals I am talking about here, so this just goes to show the huge amount of work the Greek wine industry needs to do in order to convince the world of Greece’s worth as a wine-producing nation. Not only do such responses show a complete lack of knowledge, since Greek wine is so much more than just retsina, it also demonstrates an unwillingness to give these wines a second chance, which is a great shame since, as you will discover in the following pages, retsina can be a world-class wine.

Description: