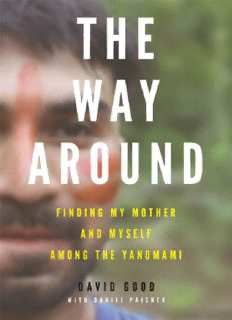

The way around : finding my mother and myself among the Yanomami PDF

Preview The way around : finding my mother and myself among the Yanomami

Dedication To my daughter, Naomi — may you grow up with a foot in both worlds, and a heart big enough to hold your entire family Epigraph “Science is nothing but the finding of analogy, identity, in the most remote parts.” RALPH WALDO EMERSON Contents Dedication Epigraph September 9, 2011: 5:43 a.m. ONE How I Got Here September 9, 2011: 8:04 a.m. TWO Reunion, Union September 9, 2011: 8:32 a.m. THREE Jungleland September 9, 2011: 9:21 a.m. FOUR Taking Time September 9, 2011: 10:27 a.m. FIVE Home September 9, 2011: 11:12 a.m. SIX My Yanomami Ways SEVEN Returning EIGHT The Good Project Photos Section Acknowledgments About the Author Credits Copyright About the Publisher September 9, 2011 5:43 A.M. UPPER ORINOCO, YANOMAMI TERRITORY We were trekking through a thick of jungle, past our old village. The deserted shabono still stood, but it had been swallowed up by grass and brush that had not been cleared in over a year. This was to be expected, of course. This part of the jungle, this deep in the territory, the flora of the rainforest can choke a clearing in no time flat. Set your machete down for any stretch and it is like you were never there. As we passed, I could see the left-behind artifacts of village life: gathered stones, clotheslines, abandoned hearths, broken cooking implements, tattered pieces of Western-style clothing. This had once been the center of activity, the focus of a people—my people—and now it was like a ghost town. Irokai. I used to live here and play here, my mother said. Well, not in this exact spot, not in this same shabono, but in this general area. I used to lie in my mother’s hammock and laugh and laugh.(Okay, maybe it wasn’t the very same hammock she uses now, but another one just like it.) I closed my eyes and imagined what our family’s area would have looked like many years ago, but I could not picture it. I had seen photographs—but, still, I could not picture it. I looked around and around but could find no touchstones, no markers to take me back twenty-plus years—something, anything to let me know I had walked this ground before. Irokai-teri. The people of Irokai. The people of my birth. The Yanomami of my home village, scattered now throughout this jungle, many of them clustered in and around the village they had once called home. The village of my mother, my cousins, my tribe. . . They are a seminomadic people, the Yanomami, and so it often happens that when a village moves they must make return trips to pick clean the gardens they have left behind while the new gardens take root. We had set out from the riverside village earlier this morning, at first light, to see what we could see. I could not think how to tell my mother I wanted to visit our old village. I could only say, “Irokai-tekeprahawe.” (“Irokai, far away.”)I could only make a going motion with my hands. Somehow, my mother understood. I was allowed to believe the trip was my idea, but it was time for a group to head out to the garden anyway. Irokai-teke. The garden of Irokai, where there was work to be done. They were going with me or without me. We would be gone for several days. There was a group of us, fifteen or so, and we would splinter into smaller groups as we made our way—usually with the men out in front. It was a long haul, but I could not put a clock on it. This part of the world, there was Yanomami time and there was outsider time. For an outsider, even for some of the missionaries familiar with the region, it could take an entire day to cover this ground. But for this group—oh, man, they plowed through the rainforest like nothing at all, cutting a new path where the old one was meant to be. Like they were walking on a city sidewalk. Barefoot, no less. Me, I was wearing sneakers, which actually were a kind of hindrance once they became wet and soaked through with mud, but the soles of my feet had not been toughened to withstand the uncertainties of the rainforest floor. As I walked at the butt end of our group, trailing my mother and a small cluster of women who seemed to take pity on me and slow their pace so I wouldn’t fall too far behind, I wondered if my bare feet would ever be tough enough for the rainforest floor—probably not, I feared. And it was not just the hard earth that caused my feet such trouble. No, there were roots and fallen branches, rocks and creepy-crawly things— all the jungle-variety nuisances you’d expect. But there were also thorns, muddy slopes, protruding sticks that could pierce the soles of your feet, bloodsucking parasitic fleas, snakes, and spiders and about a hundred different dangers, a hundred different ways I could trip, cut, or otherwise hurt myself as I scrambled to keep up. I needed a second set of eyes just to look down and watch where I stepped, while the first set of eyes could look up and ahead. The garden just beyond the communal living area still yielded its share of crops, so the Irokai-teri visited the abandoned area from time to time. This explained why there was at least the semblance of a trail. We had been this way before—we, as in my people; we, as if I belonged. It also explained how the trip came about in the first place. See, it made no sense to go on a sightseeing mission, just so I could visit the place I had once lived, but it made all kinds of sense to organize this trek in search of food. Plantains, mostly, but there were also various fruits. We would bring back what we could carry to the people of our village. The women had brought along several empty baskets for just this purpose—the jungle equivalent of bringing your own eco-friendly bags to the grocery store, I guess. I thought it was remarkable that the garden continued to thrive, after being neglected for so long. It spoke to me of the strength and resilience of my people left alone in this same jungle, untended. In this one small way, the area still lived and breathed and continued to provide. In our core traveling group there was me, my mother, my two “wives,” and another woman from the village who’d brought her infant child along for the adventure. Even the woman with the child was making better time than me. The men were way, way ahead, but they carried a much lighter load—just their bows and arrows. The men were meant to be quick on their feet, agile, able to quickly draw their weapons in case an animal appeared that might make a suitable dinner, or in case the group was attacked by enemy raiders. The women were burdened with baskets and clothes and firewood . . . and, me. It was hot—not crazy hot, the way it can get in the middle of the day, but hot enough. I was bone tired. I was twenty-four years old, in reasonably good shape, but my mother and these other women were running me into the ground. I was dragging, flagging, spent. At one point, one of my wives saw that I was having some difficulty and stopped to wait for me. She motioned to my pack, as if she meant to carry it. I responded with bluster. I said, “Yanomami keya!” (“I am Yanomami!”)As if I had something to prove—to myself, to the people of my village . . . to my mother. “Yanomami keya!” The others, they could see that I was struggling, so it was decided that our core group would stop for a rest beside a narrow creek, and as we set down our few things my mother reminded me in broken English and the generic, universal hand gestures that had quickly become our primary means of communication that this wasn’t the first time I stood on this very spot. She pointed to me. She pointed to the creek. Then she smiled and pointed back to me, and back to the creek, and I understood that I used to splash in these waters as the village elders fished, as the women washed our clothes and cleaned our pots. I had seen pictures of this very spot, I now realized. Home movies, too—shot by my father when I was only a year or so old. But my memories were once-removed. I could not recall ever being in just this place, in just this way. Here again, I could not close my eyes and picture the scene from so long ago. I could only picture the pictures I had already seen. There was nothing in my view to take me back to how I was as a child, to where I was as a child, other than my mother’s constant gesturing, and the corresponding images I could recall from the thousands of photographs my American anthropologist father had taken during his time stationed here. Still, it was a good place to be, just then, and as I set down my pack and rested along the muddy creek bed I was overwhelmed by a sense of satisfaction. That is all it was, contentment, but in that moment it was everything. To know that as a small boy I had breathed this air and splashed in these waters . . . to know that I had traveled from half a world away and then some . . . to know that I had arrived in the place where I began, reunited with my Yanomami mother and reentangled with the many branches of her family (my family!) after more than twenty years . . . It was enough to just lie out by the water and listen to the thrum of jungle activity. I thought back to what I knew of my father’s first visit to this part of the world, as a graduate student. He had come to this jungle in 1975 on a $250,000 grant from Pennsylvania State University to monitor the protein intake of the Hasupuwe-teri. He traveled with steamer trunks, medicines, food, trade goods—and enough gear to stock an Eastern Mountain Sports outlet. I was here with a backpack and a couple thousand dollars scraped together from my hourly-wage jobs. I had a machete, a hammock, maybe a tube of Neosporin., My father was concerned about my safety, of course; but he also told me I was nuts, to head this deep into the jungle with such limited resources; he told me I had no idea. He was right, of course, but I couldn’t afford to listen to him— meaning, I didn’t have that kind of money to mount an expedition of such size and scope. Meaning, I couldn’t go against my own instincts. My gut told me I was meant to make this trip—my heart, too. I had everything I needed, I stubbornly thought, and so I set out for the jungle. Yeah, I was afraid, but I accepted that I would be afraid. I was cool with it. Yeah, I was in over my head, but I’d decided early on that whatever obstacle, whatever uncertainty would come my way, I would compartmentalize my fear and find a way to power past it. I would keep laser-focused on my mission to find my mother and rediscover my indigenous roots. And here I was, in the thick of the rainforest, doing just that. I closed my eyes for a moment, and in that moment I think I fell asleep. I cannot be certain, but I believe I drifted off for a beat or two, listening to the music of my two wives, chattering in a tongue I could barely understand. The admonishing tones of the young Yanomami mother speaking to her restless child. The familiar sound of my own mother, calling to me from the other side of the creek in the sweet, singsong voice I thought I might never hear again. It felt to me like home.

Description: