The Times Literary Supplement - 22 July 2022 PDF

Preview The Times Literary Supplement - 22 July 2022

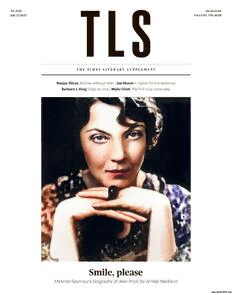

No. 6225 July 22 2022 the-tls.co.uk UK £4.50 | USA $8.99 THE TIMES LITERARY SUPPLEMENT Beejay Silcox Women without men | Joe Moran X Factor for the destitute Barbara J. King Dogs co love | Molly Clark The first true-crime play *, Smile, please Miranda Seymour's biography of Jean Rhys, by Amber Medland THIS WEEK TLS Digitally coloured portrait of Jean Rhys © TLS; ARCHIVIO GBB/Alamy Smile, please In this issue ean Rhys found literary fame late in life. The daughter of a white Creole mother from Domin- ica, she kept her lilting West Indian accent, and never quite fitted into gloomy, dank England. Between the wars she lived a rackety life on the Continent, while perfecting her prose. Publication of Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), her postcolonial prequel to Charlotte Bronté’s Jane Eyre - written from the point of view of Mr Rochester’s Creole wife, Antoinette - resurrected her from postwar oblivion. “Very tactless of me to be alive”, joked Rhys after an actress seeking to dramatize Good Morning, Midnight (1939) took out a personal ad asking for her whereabouts. After Wide Sargasso Sea a new generation sought out her bleak masterpieces from the 1930s. Yet Rhys’s fame turned to notoriety as stories about her alcoholic rages and paranoia surfaced. The Lear-like writer was the standout among three female writers profiled warts and all by David Plante in Difficult Women (1983). Life in a Devon backwater didn’t improve her temper; “when angered the ageing Rhys could still spit, bite or scratch a perceived opponent”, writes Miranda Seymour, the author of a new biography, I Used to Live Here Once, reviewed by Amber Medland. Inevitably, Rhys’s early novels were then quarried as autobiography - “critics confused the writer with her ‘less literate, more victi- mised creations”. Yet in real life, Medland writes, Rhys found agency through writing. Vainly she protested that she was not always the abandoned one. Her minimalist style and emotional honesty should recommend her to generations to come. One of Rhys’s three husbands was a bigamist, and another a fraudster. Beejay Silcox considers fictional worlds without men - “what might women dare ... if they were freed from all that patriarchal dead- weight?” - in her review of Sandra Newman’s con- temporary The Men and J. D. Beresford’s A World of Women, published in 1913. Gendercide novels first “appeared at the tail end of the women’s suffrage movement, evolving into novels of revenge and exultant female power, although nowadays they have dispensed with utopian dreamscapes”. Silcox judges that “very few de-manned books have made a lasting cultural dent”, unless they are funny. Perhaps the cynical admonition “if you want loyalty, get a dog” holds true. Jules Howard, the author of the scientific study Wonderdog, “joyfully” concludes that dogs can love. Chaser, the border collie who can recognize more than 1,000 different objects and follow a human sentence, sounds brighter than many men too. MARTIN IVENS Editor Find us on www.the-tls.co.uk @ Times Literary Supplement @the.tls ¥ @TheTLS To buy any book featured in this week’s TLS, go to shop.the-tls.co.uk 3 BIOGRAPHY & AMBER MEDLAND I Used to Live Here Once - The haunted life of Jean Rhys LITERATURE Miranda Seymour SARAH CURTIS Richmal Crompton, Author of Just William - A literary life Jane McVeigh 6 LETTERS TO THE Celts in history, How religions begin, Slavery, etc EDITOR 7 ~~ SPORT DAVID GOLDBLATT Routledge Handbook of Sport in the Middle East Danyel Reiche and Paul Michael Brannagan, editors. The Business of the Fifa World Cup Simon Chadwick et al, editors 8 POLITICS JOE MORAN Tenants - The people on the frontline of Britain’s housing emergency Vicky Spratt. Down and Out - Surviving the homelessness crisis Daniel Lavelle 10 PHILOSOPHY JAMES KRAPFL Confronting Totalitarian Minds - Jan Patocka on politics and dissidence Aspen E. Brinton. Living in Problematicity Jan Patocka. Care for the Soul - The selected writings of Jan Patocka Jan Patocka 11. THEATRE JOHN STOKES Pinter and Stoppard - A director’s view Carey Perloff MOLLY CLARK Arden of Faversham; Edited by Catherine Richardson. The Family of Love Lording Barry; Edited by Sophia Tomlinson. Love’s Cure John Fletcher and Philip Massinger; Edited by José A. Pérez Diez 14 ARTS COLIN GRANT In the Black Fantastic (Hayward Gallery) JAMES COOK The Sound of Being Human - How music shapes our lives Jude Rogers 16 FICTION KEITH MILLER The Twilight World Werner Herzog; Translated by Michael Hofmann LUCY SCHOLES The Seaplane on Final Approach Rebecca Rukeyser. Nobody Gets Out Alive Leigh Newman BEEJAY SILCOX The Men Sandra Newman. A World of Women J. D. Beresford 18 POETRY IN BRIEF ISABEL GALLEYMORE Garden Physic Sylvia Legris DECLAN RYAN Venice Ange Mlinko RACHEL HADAS My Hollywood and Other Poems Boris Dralyuk SANA GOYAL Quiet Victoria Adukwei Bulley 19 HISTORY MADOC CAIRNS Hoax - The Popish Plot that never was Victor Stater 20 LETTERS & LITERATURE MICHAEL HOFMANN Man lebt von einem Tag zum andern - Briefe 1935-1948 Irmgard Keun; Edited by Michael Bienert J. S. TENNANT Books of the Brave - Being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the sixteenth-century New World Irving A. Leonard SAMANTHA SCHNEE The Invisible Borders of Time - Five female Latin American poets Nidia Hernandez, editor 22 CLASSICS & RELIGION JULIA KINDT The Hera of Zeus Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge and Gabriella Pironti; Translated by Raymond Geuss ANNE BRAUDE A History of Islam in 21 Women Hossein Kamaly. Women Remembered - Jesus’ female disciples Joan Taylor and Helen Bond FIONA ELLIS Iris Murdoch and the Others Paul S. Fiddes 24 IN BRIEF The Schoolhouse Sophie Ward, etc 26 SCIENCE BARBARA J. KING Wonderdog Jules Howard 27 AFTERTHOUGHTS REGINA RINI The global village fractures - Our need to access the news 28 NB M. C. Being well read, Modernists at Blackwell’s, Thatcher’s poets, Larkin in Latin Editor MARTIN IVENS ([email protected]) Deputy Editor ROBERT POTTS ([email protected]) Associate Editor CATHARINE MORRIS ([email protected]) Assistant to the Editor LIBBY WHITE ([email protected]) Editorial enquiries ([email protected]) Managing Director JAMES MACMANUS ([email protected]) Advertising Manager JONATHAN DRUMMOND ([email protected]) Correspondence and deliveries: 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF Telephone for editorial enquiries: 020 7782 5000 Subscriptions: UK/ROW: [email protected] 0800 048 4236; US/Canada: [email protected] 1-844 208 1515 Missing a copy of your TLS: USA/Canada: +1 844 208 1515; UK & other: +44 (0) 203 308 9146 Syndication: 020 7711 7888 [email protected] The Times Literary Supplement (ISSN 0307661, USPS 021-626) is published weekly, except combined last two weeks of August and December, by The Times Literary Supplement Limited, London, UK, and distributed by FAL Enterprises 38-38 9th Street, Long Island City NY 11101. Periodical postage paid at Flushing NY and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: please send address corrections to TLS, PO Box 3000, Denville, NJ 07834 USA. The TLS is a member of the Independent Press Standards Organisation and abides by the standards of journalism set out in the Editors’ Code of Practice. If you think that we have not met those standards, please contact IPSO on 0300 123 2220 or visit www.ipso.co.uk. For permission to copy articles or headlines for internal information purposes contact Newspaper Licensing Agency at PO Box 101, Tunbridge Wells, TN1 1WX, tel 01892 525274, e-mail [email protected]. For all other reproduction and licensing inquiries contact Licensing Department, 1 London Bridge St, London, SEI 9GF, telephone 020 7711 7888, e-mail [email protected] TLS JULY 22, 2022 = a Z 5 = FA 2 z Zz =} 2 a E a R 2 2 mA z 5 12) seen coop MORNING, MIDNIGHT A way to earn death A life of adversity, drunkenness and literary triumph | USED TO LIVE HERE ONCE The haunted life of Jean Rhys MIRANDA SEYMOUR 432pp. William Collins. £25. LIENATION WAS A CONSTANT for Jean Rhys, in life and fiction. Born in 1890 to a Welsh doctor and a white Creole mother, Rhys was one of a few hundred whites out of Dominica’s 29,000 inhabitants. People called her a “white cockroach”. In her unfinished memoir Smile Please (1979), Rhys wrote that from the start she felt like n “outsider; a changeling”. She was always afraid. Her mother ridiculed her sensitivity and flogged her until she was twelve, at which point she gave up: “I’ve done my best. You'll never be like other people”. Her doting father trained her to mix drinks for his friends, one of whom told Rhys, then fourteen, to imagine an island where she would be his slave, bound with ropes of flowers and whipped. (“It fitted like a hook to an eye”, Rhys wrote years later. “After all ’d been whipped a lot.”) When she was sixteen Rhys left for England, expecting to find a fairy tale, but London was a disappointment. At the Perse School in Cambridge, she was nicknamed “West Indies” because of her “lilting” accent. (“Later on I learnt to know that most English people kept knives under their tongues to stab me.”) Her peers were gleeful when reading Jane Eyre: Charlotte Bronté’s Bertha, a spitting, red-eyed monster, was, like Rhys, a white Creole. Having lost a place at Rada because of her accent, she trained herself to speak softly. After her father died she joined a touring company and acted a chicken laying an egg. Soon a forty-year-old bachelor set her up in Primrose Hill. He wouldn’t marry her, but gave her a dress allowance and paid for an abortion. Self-obsession was necessary to Rhys’s writing; she scrutinized herself and lent her fictional women aspects of her personality. From the start critics confused the writer with her “less literate, more victimised” creations. In a late interview, Rhys JULY 22, 2022 sounds frustrated: “I wasn’t always the abandoned one, you know”. Still, she drew on her experience of being ditched by the bachelor for her third novel, Voyage in the Dark (1934), in which Anna Morgan slides from mistress to manicurist before sleep- walking into prostitution. Rhys herself slept a lot, then sat down and filled several exercise books with “what he said, what I felt”, ending gloriously: “Oh God, I’m only twenty, and I’ll have to go on living and living and living”. As volatile as Rhys, her characters are vain, ruthless, and vulnerable (the protagonist of one short story is advised to “grow another skin or two ... before it’s too late”). But “Rhys women” aren’t writers; they have no pur- pose; their lives depend on their sexual allure, which fades, leaving them drunk and alone. Rhys exercised her agency on the page: “I must write”, she noted in her diary. “If 1 stop writing my life will have been an abject failure.” Writing was the only way she could “earn death”. During the First World War she volunteered for two years at an army canteen in Euston station, where she worked nine-hour days. Throughout I Used to Live Here Once: The haunted life of Jean Rhys, Miranda Seymour draws attention to her subject’s “tenacity”, her “capacity to endure hardship, ill health and mental breakdowns”. Her difficulty in controlling fits of furious despair was also matched by a capacity - with a new dress, or superstition - to “believe in a glorious future”. She married three times: first there was Jean Lenglet, Dutch journalist, bigamist and jailbird (later, hero of the Dutch resistance); then Leslie Tilden Smith, a publisher’s reader who died of a heart attack in 1945; and finally Tilden Smith’s cousin Max Hamer, who proposed to Rhys while still married to his wife of more than thirty years. In 1919 Rhys moved to Paris with Lenglet. At three weeks old, their son caught pneumonia and died in hospital. The Guardian’s review of Seymour’s bio- graphy hands down the kind of cold verdict Rhys came to expect from English men: her son “died as a baby while she was out drinking”, but in her own words “he was dying, or was already dead, while we were drinking champagne”. (Lenglet bought the champagne to make up for fighting with Rhys, who wanted her son baptized.) She never forgave TLS Amber Medland is the author of Wild Pets, a novel published last year, which will be released in paperback in August herself. In 1922, when the French police turned up on the doorstep, demanding that Lenglet return to his first wife, Rhys had recently given birth to their daughter, Maryvonne. For two years she lived alone in grinding poverty. Her short story “Hunger” counts how many days - five - a woman can live on bread and coffee. Rhys believed in fate. In 1924 her short story “Vienne” (written on fleeing Vienna after Lenglet’s foreign currency dealings attracted the attention of the authorities) hooked Ford Madox Ford, who was then editor of the short-lived Transatlantic Review. There she made her debut - alongside Ernest Hemingway and Gertrude Stein - under the name “Jean Rhys” (Ford disliked her married name). Although Ford was with Stella Bowen at the time, Rhys swiftly became “Ford’s girl”. While acknowl- edging Ford as a mentor, Rhys “maintained an impenetrable discretion” about the affair. She was ignored in the memoirs of the artists who flocked around Ford. She didn’t like parties: “I’m a person at a masked ball without a mask”. James Joyce “recalled only having been asked to zip up Miss Rhys’s dress while sharing a lift”. Lenglet was jailed for two years in 1925, and later banished from France. Rhys visited their daughter, who was temporarily in an orphanage. (This wasn’t a completely unusual arrangement for parents who lived a peripatetic life; Ford’s daughter was in one too.) Bowen and Ford offered Rhys their spare room. Bowen later insisted that she didn’t know about the affair, but she probably turned a blind eye. Ford taught Rhys compositional tricks - trans- lating a “difficult passage” into French, for example, before attempting to rewrite it in English. He introduced her to Maupassant, Flaubert and the Russians. He helped her revise her sketches of Dominica and Paris, published as The Left Bank in 1927. His preface (the first twelve pages are Ford’s own recollections of Paris) gave Rhys literary clout. But her tendency to drink too much whisky and fly into a rage, claiming she was being manipulated, grew tiring. With an appetite for sex, but not drama, Ford ended the affair. Rhys drew on the heartache for Quartet (1928), her first and most auto- biographical novel. Like her stories it was praised for its “originality” and deplored for its “squalor”. In After Leaving Mr Mackenzie (1931), Rhys’s second novel, Julia Martin is recovering from being dropped - a “sore and cringing feeling”. She swaps London for Paris, where things are not much better. The “lights across the river” are “cold, accusing, jaundiced eyes”. People muttering are “shadows ... gesticulating”. Judgements are harsh and immediate (“the maid thought: tart”). To pay the rent Rhys had found work as a life model, a teacher and a typist; unlike Julia, a “habitual parasite”, she hated feeling “beholden”. Friends had to invent reasons for money arriving in her account. The novelist does lend her protagonist her own love of dressing “with voluptuousness”, however, “her hands emerging from long black sleeves”. (In Rhys’s stories, as in her life, clothes - which Seymour describes with relish - are a kind of armour against a hostile world. Perhaps using such details allowed Rhys to conjure a “sense of space around each word”.) Seymour acknowledges this and other similarities between Rhys and Julia - both grew up in hot countries, both stayed in a “cheap hotel on the Quai des Grands-Augustins” - before coming back to Rhys’s brilliance and how her prose “approaches poetry”. The world she creates in After Leaving Mr Mackenzie is both “uniquely alien and recognisably mundane”. She divorced Lenglet at his request in 1933. A year later she married Tilden Smith, who quickly became a literary wife: cooking, typing, editing, trying to limit his spouse’s alcohol consumption. They had screaming matches, sometimes in the street, often ending in blows. He warned her that she risked making no money and being identified with her characters. He had a point: Voyage in the Dark concerns a woman haunted by her Caribbean childhood. In Rhys’s original draft Anna Morgan 3 AFRICA’S STRUGGLE ea Lil c BENEDICTE SAVOY A major new history of how African nations, starting in the 1960s, sought to reclaim the art looted by Western colonial power Jhumpa Lahiri Luminous essays on translation and self-translation by the award-winning writer and literary translator AND NOT BELONGING MARY JACOBUS A look at how ideas of translation, migration, and displacement are embedded in the works of prominent artists, from Ovid to Tacita Dean {> PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS BIOGRAPHY & LITERATURE Jean Rhys dies during a botched abortion. But in the mid- 1930s nobody wanted a depressing book: the publisher accepted it on condition that Anna would survive. In the reluctantly revised version Anna watches a chink of light under the door “like the last thrust of remembering before everything is blotted out ... I lay and watched it and thought about starting all over again. And about being new and fresh”. Reviewers expressed familiar regrets about the author’s obsession with “dreadful” and “difficult” subjects. Whisky impeded Rhys’s progress on her fourth novel, Good Morning, Midnight (1939). She also threw her husband’s typewriter out of the window. Sasha Jansen, an ageing ex-mannequin, is fierce, bitter, sarcastic and paranoid. Her fur coat has seen better days. She tries drinking herself to death, then roaming the streets to forget her past. Here is a woman who has called in every favour; she knows that death will come when there is nobody left to help: “When you sink you sink to the accompaniment of loud laughter”. Rhys’s private writing was often wry, and her fiction darkly funny. Seymour points out the relief brought by moments of silliness: “Very light”, remarks a chambermaid in a room facing an external wall. The reviews were terrible. Rhys didn’t publish again for twenty-seven years. In May 1940 Hitler invaded the Netherlands. All lines of communication were cut; there was no way for Rhys to know if Lenglet and Maryvonne were still alive. Tilden Smith got a desk job with the RAF; they relocated to Norfolk, where Rhys was arrested for being drunk and disorderly. In 1942 husband and wife were drinking in a pub when Rhys shouted “Heil Hitler”. It was reported, and Tilden Smith lost his job. After the war they moved to Dartmoor, where he died. Transmuting the loss into her short story “The Sound of the River” brought Rhys close to breakdown. Her dread of publicity throws obstacles in the path of any prospective biographer - she destroyed letters - and Seymour is the first of her biographers actually to visit Dominica and offer a long-overdue exploration of its impact on her work. She doesn’t begrudge Rhys her privacy, but laments her “pecu- liar” coyness in concealing how much she read. Seymour’s investigations into Rhys are inseparable from her sensitive close readings of the novels. She is shrewd and careful (“it’s reasonable to assume”), unlike Rhys’s first biographer, Carole Angier (Jean TLS Rhys: Life and work, 1985), who was more interested in Rhys as a badly behaved woman than as a writer, and filled in the gaps in her (valuable) research with speculative italics, diagnosed a personality disorder and asserted that Rhys “could only write instinctively, unconsciously”. It’s hard to imagine anyone saying that about Hemingway, who was also published by Ford. Harder still not to wonder about Rhys as a mother. Two months before the war ended she finally learnt that Maryvonne was safe. In 1948 Mary- vonne scraped together enough money to come over and introduce Rhys to her baby daughter. She had been working for the Dutch resistance while Lenglet rescued downed RAF pilots. Speaking of her marriage, Maryvonne neglected to mention that the danger of “being recognised by a German registrar had been so great that [she] smuggled five grenades into the ceremony”. For Rhys’s part, motherhood did nothing to narrow her ruthless self-awareness. On one occasion she wrote to Maryvonne, apolo- gising for having never “helped you enough or been the right sort of person for you”. To a friend, Maryvonne admitted that Rhys had “a supreme egocentric view of life”, but understood that such self-absorption was “a must for her kind of writing”. Maryvonne emerges from this account as a stoic who did all she could to keep the peace. Perhaps, as Seymour says, she understood her mother’s “childhood terrors”. Perhaps, too, Rhys was easier to manage at a distance. Rhys’s third husband, Max Hamer, a solicitor, made her laugh and owned a house in Beckenham, but he was gullible and optimistic, a magnet for “silver-tongued crooks”. Often Rhys was left alone, which she hated. Her consolations were her books and three cats. When two of them were killed by the neighbours’ dog, Rhys threw a brick through the neighbours’ front window, resulting in the first of several visits to Bromley Magistrates’ Court. Out of necessity, Hamer and Rhys took in lodgers. The first argument was triggered by a racket at night while Rhys was writing. Drunk, Rhys hurled antise- mitic abuse at her tenants before accusing a police- man called to the scene of being a member of the Gestapo. In a footnote Seymour acknowledges that Rhys’s “insults were frequently anti-Semitic but almost always inconsistent”. After several such incidents she spent five days in the hospital wing at Holloway Prison, where she gathered material for her short story “Let Them Call it Jazz”. Then, in 1950, Max wound up in Maidstone Prison for attempted fraud. On his release they settled in Devon. The literary world thought Rhys was dead. But the BBC learnt of her whereabouts via an advertisement in the New Statesman, and Good Morning, Midnight was adapted for radio. The broadcast, in May 1957, elicited letters from Francis Wyndham and Diana Athill, editors at André Deustch, to whom Rhys rashly promised a novel by the end of the year. That promise was empty, but a novel did emerge. It took Rhys seven years to finish Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), and in describing the circumstances of its creation Seymour’s book becomes something of a psychological thriller. Years past her deadline, Rhys drafts and redrafts, flying into drunken rages and tearing up her pages. Local boys call her “a witch”. “I am envied and hated”, Rhys wrote to a friend in 1963, adding, two months later, “the gossip is dreadful”. Max was in and out of hospital, and in her correspondence Rhys “misrepresented her sit- uation” as hopelessly lonely, even though “loneli- ness was always more a state of mind than a fact of her existence”. (Or, as Emily Dickinson, from whom she borrowed the title for Good Morning, Midnight, wrote: “It might be lonelier / Without the Loneliness”). Rhys seemed oblivious to how many people were looking out for her. After losing her temper over a barbed-wire fence, she struck up a rapport with the local vicar. Soon he was visiting regularly, bringing with him a bottle of whisky and shocking the villagers. During Rhys’s nineteen years in Devon, Seymour posits, her correspond- JULY 22, 2022 © FAY GODWIN/BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD/BRIDGEMAN ence makes it almost possible to predict the onset of a mental health crisis by the increase in her allusions to the unwelcome presence of largely imaginary rodents”. She wrote to Wyndham about creating a barricade: “quite useless of course. Also there are alarming sounds from above where the hot water pipes are. (Things larger than mice?)”. In 1960 someone prescribed Rhys amphetamines. She compared the sensation the bright red pills brought on to flying. Her progress was punctuated by fights with Max and fits of hopelessness. Her publishers tried everything to keep her writing: enlisting a local typist, telling another to feign an allergy to alcohol. Nothing worked, yet in May 1963 Wyndham received “the makings of an extraor- dinary book”. By 1964 Rhys was “living entirely in the world of her novel”. Just as she was finishing the novel, Max died. Maryvonne visited, but resisted pressure to become a full-time carer: “I am very lonely”, Rhys said. “Perhaps you will be the miracle that will bring me to life”. Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) tells the story of Bronté’s “mad wife in the attic” before Rochester (who is not mentioned by name in Rhys’s novel) marries her for money, drives her mad with cruelty and locks her up in England. A prequel to Jane Eyre, it is set after the emancipation act of 1833: Rhys wanted to challenge Bronté’s crude portrayal of the white Creole class, but in doing so she had to confront her family’s complicity as descendants of slave owners. The operations of historic guilt are sensually personal. Just as, to Rhys’s way of think- ing, Dominica - beautiful but menacing - seemed to have rejected her, so the Coulibri estate in Jamaica, where Antoinette Cosway (whom Roches- ter renames “Bertha”) grows up, is haunted, a place where the “smell of dead flowers mixed with the fresh living smell”. Critics didn’t respond to Wide Sargasso Sea as the publishers hoped; it wasn’t read in its “colonial context”, but as an affront to Bronté. Yet it won the W. H. Smith award in 1967; and in 1972, in the New York Review of Books, V. S. Naipaul recognized Rhys as a great writer, describing her women “not as self-portraits or alter egos” but women “cruder, and less gifted than herself”, “schooled by their society in the arts of survival”. Rhys is likely to remain primarily known to readers for this novel, and Seymour’s biography will enrich their understanding of it. In the final chapter of this compelling biography, Seymour adopts the tone of a resigned yet affect- ionate godmother. After it became clear that Rhys could no longer live alone, she moved into the Hampstead house of Diana and George Melly, where a suite was redecorated in her favourite pink. Of the three months she spent there, the first two were “an almost unqualified success”. Rhys thrived as the “acknowledged queen” of the bohemian house- hold. Asked whether, if she had her life over again, she would choose to write or be happy, Rhys cried out, “Oh, happiness!”. There were good times: shopping trips; evenings at Ronnie Scott’s; in 1978, a CBE. But with age the soft voice and manners that veiled a forceful will grew thin. She screamed and spat. She pounded the floor when she wanted another drink and raved about being trapped by some woman who “produced hideous clothes which her imprisoned guest was then compelled to buy”. Rhys, feeling “both beholden and insecure”, passed beyond reason. She threatened to slash her host’s paintings. Writing to a friend in Paris, Diana Melly admitted that she had thought she would be able to make Rhys happy: “I can’t do that, I can’t even make her feel all right”. Back in Devon, Rhys suffered a series of falls. In 1979, for six weeks, she lay in the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital. Paying a visit to her, a friend didn’t recognize her without the customary make-up. The hospital misspelt her name as “Joan” above the bed where she died. “Well, you are a fighter”, one of her nurses had said when Rhys insisted on trying to walk without a cane. Maybe so, she wrote in one of her final notes, but “What exactly am I fighting for?”. = JULY 22, 2022 BIOGRAPHY & LITERATURE Just Richmal An author who started writing for adults but became an enduring hit with children SARAH CURTIS RICHMAL CROMPTON, AUTHOR OF JUST WILLIAM A literary life JANE McVEIGH 310pp. Palgrave Macmillan. Paperback, £17.99. O ANYONE WHO GREW UpP in the 1950s, the Just William books were as the Harry Potter books are to children today. We girls identified with the rascally but well-meaning William rather than the lisping Violet Elizabeth. Like the eleven-year-old William himself, we considered Miss Bott soppy, ignoring how feisty she was, as she shouted, “‘[i]Jf you don’ play houth with me I’ll thcream n’thcream till I’m thick. I can’”. Jane McVeigh is an Honorary Research Fellow in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Sarah Curtis was a Youth Court Magistrate HOW THE CLINIC MADE GENDER The Medical History of a Transformative Idea SANDRA EDER “A stunningly original book.’ —Thomas W. Laqueur, author of Making Sex Paper £24.00 ISBN: 9780226819938 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS press.uchicago.edu Trade Enquiries to Yale Representation Ltd. [email protected] 020 7079 4900 TLS the University of Roehampton, where the Richmal Crompton Collection is housed. In her biography of Crompton, she explains with insight and sensi- tivity how their creator conjured up William’s misadventures from 1919 until her death in 1969, and why they are still read or listened to - a record- ing made by Kenneth Williams of some of the sto- ries was reissued only a year ago. She shows that Crompton’s output was astonish- ing. As well as the thirty-seven William books, over five decades Crompton published forty novels and more than ten volumes of other stories. The Will- iam books were initially intended for adults, per- haps as a way to bemoan or cherish the exploits of the readers’ own young. Born in 1890, in Bury, Crompton was schooled in classics by her father, read classics at Royal Holloway College, then taught classics at Bromley High School from 1917 for six years. In the period during and after the First World War, there was a lack of young men whom Crompton might have met and married; this was also a period, after the death of her father, when she supported the rest of her family through her writing. She suffered polio in her early thirties, which permanently damaged her right leg. She always concealed her disability. She had a mastec- tomy in her forties, but she never seems to have complained about her physical lot. A devoted daughter and aunt, Crompton was witty but unassuming when her books became famous. She continued to live an orderly life in Kent. She said in 1952 that, at the beginning, she had written the stories “rather carelessly and hur- tiedly”; but she was serious about her writing. The first Just William film was made in 1939 and her celebrity grew after William stories were broadcast on the wireless from 1946. She did not stop writing William’s cursus opprobrium until 1969. It is clear from McVeigh that it is misleading to put the William books in a category. They cannot be shelved as humour or farce because the adven- tures of the gang are so carefully placed between fantasy and realism. Adults have always enjoyed them as well as children. As McVeigh says, there is much that is ridiculous in them, but nothing vicious. It is amazing to learn from her that the stories were censored in Franco’s Spain because they were considered subversive, but perhaps some mothers might agree that William’s antics were intolerable. His background is middle-class and red- olent of the home counties of Crompton’s era, but his speech is idiosyncratic. McVeigh does not explore why Crompton created William’s diction, with his dropped consonants and elisions, rightly assuming that readers would work out what Will- iam, Ginger and the rest of the gang were saying. McVeigh does not think Crompton had any particular models, but conjured up her characters and the dialogue in the stories partly from aspects of people she knew and snippets of conversations she overheard, and partly from her imagination. As her niece Margaret said, “She had a superb sense of the ridiculous”. She would scribble on scraps of paper everyday conversations she remembered. McVeigh attributes to Crompton an open personal- ity that enabled her to be on terms with Harold Macmillan, her publisher before he became prime minister, and to remain polite when interviewers did not know she had written many novels in addition to the William sagas. This is a model biography for the way it delivers the facts about the life of its subject and analyses the attraction or magic of the stories for subsequent writers, as well as readers across generations. The best praise of this biography is that it will send many readers back to encounter the thrills of reading once more of William’s misadventures. = LETTERS TO THE EDITOR How religions begin In discussing the argument over whether Axial Age religions spring from inspired visions of ineffable reality or anthropomorphic fabri- cations of “Moralizing High Gods” that serve to keep people in order, Karen Armstrong seems to smuggle in another utilitarian account of religion (July 15). She asks why religions have persisted in trying to comprehend the incomprehens- ible, and argues that doing so lessens suffering and sustains a moral imperative, the so-called Golden Rule, of treating others as you would wish to be treated. Such a principle is hard to imagine com- ing from a Moralizing High God, who would presumably intimidate rather than suggest compassion. But Armstrong also distracts from the religious impulse, namely that religious practitioners, in a variety of ways, and in different times and places, have felt themselves to be participating in a living reality and aligning with what is most funda- mentally true. This brings its own reward, and without such a root, any religious fruit, socially and per- sonally beneficial or not, will die. ™@ Mark Vernon London SE5 Slavery May I add a note to John Samuel Harpham’s fascinating review on slavery (July 8)? Apart from his neat summary of the chief defini- tions of servitude, one should also include the tradition that stretches from Franz Baermann Steiner (1949) via Paul Bohannan (1963) to Claude Meillassoux (1986) and David Graeber and David Wengrow (2021). This has become one of the most dominant schools in the modern scholarship on slavery. Steiner’s encyclopedic analysis of the topic, written as a penance for the Jews incarcerated in the camps, hinges on the insight that slavery amounts to kinlessness: it is to philosophers and poets to cult Celts in history St Simon Jenkins is a fine journalist. However, his response (Letters, July 15) to my review of The Celts: A sceptical history (July 1) is weak on facts and strong on rhetoric. Tilting at windmills, he associates me with ideas I have never espoused, such as “a coherent tribe of ‘Celts’ charging across Europe”. I described as a fantasy Jenkins’s idea that pre-Roman lowland Britain was Germanic-speaking. He replies that he is “not a ‘fantasist’ in finding it implausible that easterners spoke a Celtic language under the Romans, then switched almost overnight to a Germanic one”. That is a quite different proposition, and not my view; I think it likely enough that there were some Germanic- speakers in eastern England before the Romans left and agree with Peter Schrijver that many lowland Britons would have been bilingual in Latin and Celtic by then. Regarding “the eradication and replacement of mil- lions of ‘eastern Celts’”, Jenkins carelessly asserts that I “cannot have read Susan Oosterhuizen’s 2019 study of the evidence”, even though I discussed Oosthuizen’s book - spelling her name right - and mentioned con- trasting views. Jenkins notes, with apparent dismay, that a Saxon conquest “is still taught in schools” (ie Key Stage 2: “Anglo-Saxon invasions, settlements and kingdoms: place names and village life”). My opinion, as quoted extensively by Oosthuizen, is that Gildas, Bede and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle should not lead us to present an over-lurid picture of these invasions. If the Department for Education took notice of Jenkins, however, that part of Our Island Story might disappear altogether. For which there’s a precedent: in 1284, following the Edwardian conquest, the Archbishop of Canterbury commanded the Welsh bishops to teach that Britain’s first peoples, long before the Welsh turned up, were a “Germanic race called Albyon, from whom come the Saxons”. Like Archbishop Pecham, Sir Simon tries to prop up the Union by peddling myths and caricatures. Wouldn’t killing Home Rule by kindness be more effective? He begins his letter by quoting - or rather misquoting - Tolkien’s remarks on the “fabulous Celtic twilight”. Ignoring Tolkien’s con- text, Jenkins supposes him to be criticizing “Celtic studies”. For Tolkien it was in fact “people outside the small company of the great scholars, past and present” who dwelt in that “twilight ... of the reason”. People like Simon Jenkins. @ Patrick Sims-Williams Aberystwyth Simon Jenkins’s account of post-Roman Britain ignores the evidence of place names, which incoming colonizers often adopt or adapt. German settlements in the east often retained the Slavonic termination “itz”, as in Colditz. Incoming Europeans, overwhelm- ing the First Australians, still preserved versions of local names such as Cootamundra, while Norman barons simply added the family moniker to their new manor, as in Ashby-de-la-Zouch. Yet place names of Celtic origin are conspicuous by their absence in southern and eastern England, apart from London itself, and possibly Penge. Anglo-Welsh hybrids such as Penkridge occur well to the west, on what may once have been a linguistic boundary. Thus, place-name evi- dence points not to “genocide”, but to the widespread “ethnic cleansing” reported in written sources. The Old English word “walas” (“Welsh”) always meant “foreigners”. John Coutts Stirling neither possession, power nor a form of objectification, but - in a view developed from Simmel’s formal sociology - the state of being excluded from kinship rela- tions. This radical isolation enables the other states of being Harpham lists. Today, after decades of obscu- rity, Steiner’s thesis “A Compara- tive Study of the Forms of Slavery” has thankfully been made access- ible in digital form by the Bodleian Library. At last it has become possible to understand Steiner’s lth ests, from novelists “ommentators. Subscribe to the podcast today at the-tls.co.uk/podcast compendious project. His vast field of comparison stretched from Asia to Africa and North America; and his system embeds slavery into a wider pattern of institutions com- prising what he calls “detached persons”. The slave inhabits a “no-man’s-land” that remains unstructured by social life. He/she is the totally isolated being. This hugely ambitious, curiously incom- plete DPhil remains one of the most insightful studies of the field. ™@ Jeremy Adler King’s College London Suze In addition to what Peter Cogman offers as the “realism” of Suze (Let- ters, July 15), it has a few interesting cultural ramifications. Bob Dylan’s first long-term girlfriend was born Susan Rotolo, but didn’t much like her forename. She did, though, like Picasso’s paintings, and when she came across “Glass and Bottle of Suze”, as she tells us in her auto- biography, A Freewheelin’ Time, she found the alternative by which she has been known to generations of Dylan fans. In Paris in 1956, Sylvia Plath came across a kiosk adver- tising the drink and was sparked by it into her very lively drawing “Colourful Kiosque near Louvre” (reproduced in Drawings). Peter Cogman implies that the drink itself hasn’t travelled far beyond its national borders; but its representations have. @ Neil Corcoran Oxton, Wirral TLS Navel gazing Any god who can make a creature as gorgeous as Michelangelo’s Adam from the dust of the earth (Genesis 2:7) clearly has the skill to create him with or without a navel. (See Robert J. Asher’s review of In Quest of the Historical Adam by William Lane Craig, June 17.) The presence of a navel, the scar left by the detachment of the umbilical cord that had connected baby and placenta, is consistent with the now usual development and birth of a human baby, but it is not proof of it. Indeed, at the time of Adam’s creation, there was no female human around. Eve, according to Genesis 2:22, was created after Adam had had time to name all the creatures of Eden. If Adam was the product of a conventional pregnancy, he must have been conceived almost nine months before the creation of the universe, and have matured from newborn to well-developed adult during the twenty-four hours of the sixth day of creation. Earlier on that sixth day, before creating Adam, God created the terrestrial animals, specifically including cattle (Genesis 1:24), another mammalian species. Did they also have unnecessary navels? Literal analysis becomes ridicu- lous. Let us learn from the eternal stories and enjoy the images while we can. A little further down the Sistine Chapel is the Last Judgement. @ Anthony Woodward Portland OR The Buddha's Tooth Natasha Heller, reviewing John S. Strong’s The Buddha’s Tooth (July 8), asserts of the venerated Dathadhatu at Kandy that “there was no question that it was a relic of the Buddha”. No question in whose mind? To this day there may be no question of its authenticity in the minds of many Sri Lankans, Thais and other devout Buddhists, but not everyone has been con- vinced by it. In October 1858 two Burmese bonzes arrived in Kandy, sent by the Burmese emperor to examine the tooth in order to ascertain by comparison the authenticity of a purported tooth of Buddha, eight inches in length, preserved at Ava. The governor gave permission for the tooth to be displayed and a general festival ensued, with the temple magnificently decorated and the entire population flocking for this rare opportunity to view it. According to one observer (see J. Barthélemy Saint-Hilaire’s The Buddha and His Religion, 1914): “The piece of ivory which is supposed to have graced the Buddha’s jaw is about the size of the little finger; it is of a fine tawny yellow colour, slightly curved in the middle, and thicker at one end ... On looking at the transversal veining of the ivory, it is easy to see that it is only a piece of a tooth, and not a complete one; but it would not be advisable in this country to throw a doubt on the perfect authenticity of an object held in such veneration”. The Bur- mese priests were also, apparently, unimpressed, donating only “a paltry sum” to the temple. ™ Graham Chainey Brighton Et in Arcadia Other readers who are as impressed as I am by Jonathan Bate’s review of Paul Holberton’s A History of Arcadia in Art and Literature (July 15) might be interested to know that Arcadia has had yet more American afterlives in geography and liter- ature. Early mapmakers designated the whole North American coast north of Virginia as Arcadia. New France was founded in an area known as Acadia - it was Cham- plain, a Canadian founding father, who removed the “r”. In their eighteenth-century contest with France, the British “ethnically cleansed” the area, removing its inhabitants to American territories, especially Louisiana. When Long- fellow wrote of this process in his narrative poem Evangeline (1847) he saw the significance of the nomen- clature and another lost paradise. The poem has been several times adapted by American and Canadian film-makers. BJohn M. Smith Basingstoke, Hampshire CONTACT 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF [email protected] JULY 22, 2022 © KHALED DESOUKI/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES AY cial A political game How the Middle East has bought up global sporting events ROUTLEDGE HANDBOOK OF SPORT IN THE MIDDLE EAST DANYEL REICHE AND PAUL MICHAEL BRANNAGAN, EDITORS AO6pp. Routledge. £190. THE BUSINESS OF THE FIFA WORLD CUP SIMON CHADWICK, PAUL WIDDOP, CHRISTOS ANAGNOSTOPOULOS AND DANIEL PARNELL, EDITORS 276pp. Routledge. £120 (paperback, £34.99). N QaTAR THIS NOVEMBER and December, the Fifa World Cup will be played for the twenty- ._second time, but in a number of ways it will be unique. The timing, necessary to avoid the blistering heat of a Gulf summer, and which has required the reordering of the entire world football calendar, is a first. It will also be the first sporting mega-event to be held in the Middle East. At a conservative estimate the Qataris will have spent more than $200 billion on a transformation of the country that has centred on staging the tournament, making it the most expensive ever, while the media coverage of the conditions of the millions of migrant workers who have built the stadiums and associated construction makes it the most closely scrutinized ever. Finally, given recent viewing trends and the country’s favourable time zone between Europe and Asia, Qatar 2022 will attract the largest broadcast audience ever for a World Cup, Olympics or anything else. Given how little has been published on sport in the Middle East, or on the non-sporting side of the World Cup, these two books are welcome contributions that put Qatar 2022 in context: The Routledge Hand- book of Sport in the Middle East by offering a range of essays on the history and the cultural and political significance of sport in the region; The Business of the FIFA World Cup by covering the ways in which past tournaments have been planned, financed, built, organized and marketed. Two clear themes emerge from Danyel Reiche and Paul Michael Brannagan’s collection. First, that in the Middle East, football is king. This is true in much of the world, but the gap between the game and any sporting competitors is much more pronounced here than anywhere else. Why this should be remains unclear. Given the sport’s huge cultural and political JULY 22, 2022 weight, the second theme is no surprise; football across the region is inexorably and tightly bound to political power and political identities. Again, this is not a relationship on which the Middle East has a monopoly, but one in which it clearly excels. In some states football is primarily a space in which domestic political conflict is played out. In Iran it has pitted conservatives against progressives, especially over the enduring and much contested ban on women attending men’s football matches. In Syria the Assad regime has used the men’s national football team as an ersatz symbol of national unity. In Egypt football has been an arena for conflict between successive regimes and the public for decades. The ultra groups that support the country’s biggest teams - Al Ahly and Zamalek - challenged Hosni Mubarak’s rule inside the stadium, and in 2011 were part of the coalition that toppled him. Since then their opposition to the military regime has seen them prohibited and politically crushed. In other states, above all in Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar, football is primarily a matter of inter- national politics, presence and influence. All three countries have bought a big European football club (Newcastle United, Manchester City and Paris St Germain) and staged minor international football tournaments. Qatar has gone much further than its larger neighbours: establishing the pre-eminent foot- ball broadcaster in the region, BeIN Sports; hosting the World Cup this year as the apex of its foreign policy of visibility; and making the game a primary instrument of urban development. These policies may be recent, but a number of contributions to the Handbook remind us that football has deeper domestic roots in Qatar than one might imagine, with the country’s accession to Fifa in 1970 and first international football games, then its miraculous journey to the final of the 1981 under-20 World Cup (beating Brazil and England on the way), serving as vital moments in the collective imagining of the Qatari nation. Some of the best chapters in the book deal with minority sporting interests, helping to correct the cruder, flatter accounts of Middle Eastern societies that an exclusive focus on football generates. The ethnic complexity of societies is illuminated by the story of David Saad, a Lebanese Jewish judoka excluded from international competition in the 1970s as Lebanon’s repression of its Jewish community intensified. (He eventually competed at the Montreal Olympics in 1976.) An excellent chapter on the story of cycling in Qatar conjures up a bike-friendly Doha before the motorway and the 4x4, and explains how TLS An Egyptian protester waving Al Ahly and Zamalek football flags, 2012 David Goldblatt’s books include The Age of Football: The global game in the twenty- first century, 2019 European cycling teams came to love the Tour of Qatar, whose harsh desert environments and fear- some crosswinds made it a gruelling and much respected preparation for the cycle tour’s European Spring Classics. The pieces on the Bahraini royal family’s support for professional mixed martial arts (MMA), and the popularity of falconry as a “heritage” sport in the UAE are no less absorbing. It is a shame, then, that there was no space in the collection for cricket - the game of the South Asian migrants who have built the modern Gulf - or horseracing - long the obsession of the region’s aristocrats and monarchs. Above all, there was no space for a piece on Islam’s changing relationship to sport. Religion is by no means the only or dominant cultural force in shaping sport in the region, but in some places - Iran, for example - and on some issues, including women’s participation in sport, it has been profoundly important. The Business of the Fifa World Cup has its moments. The account of the first tournament, held in Uruguay in 1930, draws some nice parallels with the present - a small, almost unknown country of fewer than three million people using the World Cup to adver- tise itself and its social and economic progress to the world. For the most part, however, the historical contextualization that should have been on offer is disappointingly thin. The book’s coverage of the role of domestic politics in shaping tournaments, the impact of critical global media coverage and the staging of political protests, all vital fields of research in looking at Qatar, are at best pedestrian. In the case of Russia 2018, for example, no mention is made of the regime’s long-standing use of football as a political instrument at home, or the way in which the huge anti-pension-law protests that swept the nation in non-World Cup cities were obscured by the tournament. Nor is there much in the account of past stadiums and urban development programmes at World Cups to clarify the scale and intentions behind Qatar’s construction bonanza - bigger than all the other twenty-one World Cups put together. Politics aside, much of the book, the editors explain, is focused on questions of “leadership and brand management”, and covers the institutional and procedural infrastructure of actually making the media spectacle happen. These chapters on, among other topics, competition design, securing the integrity of the games and making the tourn- ament environmentally sustainable, not to mention marketing, broadcasting and social media strategies, certainly lay bare the long to-do lists of World Cup organizers, but offer little insight into the political processes and choices they conceal. A final, stronger chapter on Qatar and culture takes us a little further down this road, looking at the ways in which the norms of global sporting events and federations, shaped in the global north, interact with the culture of a conservative and Islamic society such as Qatar, where homosexuality remains illegal and alcohol consumption is strictly regulated. A similar dynamic, underinvestigated in both of these books, has been the impact of global trade unions, human rights and media organizations on Qatar’s kafala system of labour migration and control which has effectively been dismantled over the past decade. This is a significant absence. While that process is incomplete, and the new labour system is hardly Scandinavian, it probably constitutes the single biggest domestic policy change induced by hosting a sporting mega-event - another superlative for Qatar 2022. It is a consequence of the now unparalleled popularity, visibility and significance of football, and, compared to recent hosts of flagship global events like China or Russia, the relative openness of Qatar to the world’s media, and its greater vulnera- bility as a small state to global pressure and negative coverage. At their best these books help us to make a bit more sense of these extraordinary events, but neither, even in passing, can begin to address the question it all prompts. Why is football, of all things, asked to bear this kind of political weight? Housing the homeless The flaws in a property-owning democracy TENANTS The people on the frontline of Britain’s housing emergency VICKY SPRATT 352pp. Profile. £20. DOWN AND OUT Surviving the homelessness crisis DANIEL LAVELLE 304pp. Wildfire. £18.99. IKE ACCESS TO CLEAN, DRINKABLE WATER, the right to adequate housing is recognized by the United Nations. In the UK, in the space of a generation, this right has been gradually eroded by stark housing inequalities. These inequalities are the product of political will, market ideology and the unintended consequences of both. The forty- year property boom has been so spectacular that many houses now earn more in equity than their occupants do in their jobs. Attempts to help those priced out of the market through optimistically named “affordable housing”, stamp-duty cuts and Help to Buy schemes have only tinkered at the edges of the problem or inflated the market further. Meanwhile, the selling off of council housing has pushed most tenants into the private rented sector, where they have few of the legal protections of tenure available in other European countries. Two new books by Vicky Spratt and Daniel Lavelle address this intricate ecosystem of housing inequality and the ways in which it is reshaping Britain’s social and economic landscape. Both authors have lived at the sharp end of the problem. When Spratt was seven she learnt never to answer the door to bailiffs, but still her family lost their home. As a young adult she rented tiny box rooms in houses with damp and mould, and lost a fortune in deposits to dodgy landlords. She is now the i Paper’s housing correspondent, writing not about property hotspots and fantasy house hunts, but about the human costs of the housing crisis. Lavelle grew up in care, moving between special boarding schools, foster homes and children’s homes. After leaving university he was homeless for two years, living in tents and hostels, or sleeping on friends’ sofas. In 2019 he co-wrote the “Empty Doorway” series in the Guardian, recording the lives of home- less people who died on the streets. Tenants is the more densely researched book, being based largely on interviews Spratt conducts The Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation Announcing the Judges of the 2022 Prize Charis Olszok Katharine Halls Susheila Nasta Becki Maddock Charis Olszok (Chair),Associate Professor, Modern Arabic Literature, University of Cambridge Katharine Halls, translator of fiction & plays, joint winner of 2017 Sheikh Hamad Translation Award Susheila Nasta MBE, Wasafiri magazine founder, Professor Emerita Queen Mary College & the Open University, Royal Society of Literature Council Member, Honorary Fellow, the English Association Becki Maddock, Banipal Trustee, toponymist, linguist, translator, Royal Geographical Society Fellow View the full list of 2022 entries at www.banipaltrust.org.uk/prize/award2022 The Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize aims to raise the profile of contemporary Arabic literature as well as honouring the important work of individual translators in bringing the work of established and emerging Arab writers to the attention of the wider world. It was established in 2006 by Banipal, the magazine of modern Arab literature Banipal Trust for Arab Literature, | Gough Square, London EC4A 3DE [email protected] * www.banipaltrust.org.uk f facebook.com/SaifGhobashBanipalPrize TLS Joe Moran is a Professor of English and cultural history at Liverpool John Moores University with evicted tenants, grassroots activists, support workers and experts in housing law. Down and Out is rawer and more personal, combining Lavelle’s own story with those of the insecurely housed and homeless people he keeps in touch with from his time in care and in hostels. Spratt focuses mainly on tenants facing or experiencing eviction; Lavelle explores a twilight world of sofa-surfing, hostels, night shelters and rough sleeping. Taken together they make plain how paper thin is the divide between the cheaper end of renting and being thrown out on to the street. They show that all it takes to be made homeless is to be surprised by illness, redundancy, a break-up or simply a landlord who decides on a whim that they want you out. Section 21 of the Housing Act 1988 allows private landlords to evict tenants at short notice without giving a reason. In the Queen’s Speech of December 2019 the government pledged to abolish these “no-fault” evictions, but it has yet to do so. Both books consider the Thatcher era to be, in Spratt’s words, “ground zero for the mess we are in now”. The 1980 Housing Act gave millions of council house tenants the right to buy their homes, at market discounts of up to 50 per cent. As Spratt points out, this was no rocket boost for home- ownership, which in England has increased only slightly from 56.6 per cent in 1980 to 64.6 per cent in 2020. More than 40 per cent of ex-council homes sold under Right to Buy are now owned by private landlords. For Spratt, the key driver of housing inequality was the political decision to outsource he rental sector to unqualified and unregulated individuals, private landlords, many of whom have neither the time nor the resources to manage their properties properly. Nearly half of housing benefit, about £10 billion a year, goes straight to them. Lavelle, with typical pungency, calls Right to Buy the greatest heist in modern history, a heist perpe- trated under the guise of giving people a stake in public assets they already had a stake in”. In truth, as the more restrained Spratt concedes, Right to Buy was not an original Thatcherite policy. A less heavily discounted version of it appeared in the Labour Party’s election manifesto in 1959. The traditional Conservative policy of encouraging home owner- ship - Anthony Eden’s espousal in 1946 of a “nation- wide property-owning democracy” - gradually became a cross-party consensus in the postwar years. Labour retained plans for ambitious council house-building, but New Labour shelved them as it tailored its policies to existing homeowners. Between 1998 and 2010, 6,330 council homes were built, just over a third of the total built in 1990 alone, the last year of the Thatcher government. The 2008 financial crash made things vastly worse in two ways. First, banks wanted bigger deposits and tightened affordability checks for mortgages. They ploughed money into buy-to-let mortgages, with investors being seen as a safer bet than first-time buyers. This pushed many more people into renting. Second, austerity made life more brutal for renters on low incomes. In 2010 George Osborne cut hous- ing benefit and barred single people under thirty- ive from claiming it to live in a place of their own. Cuts to local-authority budgets meant less money or hostels, shelters and drug and alcohol depend- ency services. Councils are now so strapped that they operate what Lavelle calls “a misery contest or housing, a sort of X Factor for the destitute”. While living in a tent along a bridle path in Saddle- worth, Greater Manchester, he was told he was not a “priority need” because he did not present with any other vulnerabilities. He was “homeless, but not homeless enough”. These two effects of the financial crash combined catastrophically with one non-effect: house prices JULY 22, 2022 © GUY CORBISHLEY/ALAMY and average rents carried on rising. Adding more renters to the mix drove up demand, and landlords put up prices accordingly. Each chapter of Spratt’s book is preceded with data on the sales and rental market in the area she is writing about, which underlines how hopeless the situation is for many. In Peckham, south London, for instance, the average price of a flat in 2021 was £450,865 and the average monthly rent for a one-bedroom home was £1,394. Housing inequality bears out Claudius’s maxim that sorrows come “not single spies, but in battalions”. Its victims are invariably dealing with contributory and aggravating factors: casualized work, stagnating wages, welfare cuts and debt. Spratt compares the housing crisis to a virus that “infects its hosts and multiplies to make everything more difficult for them”. Living in cramped, ugly, broken-down surroundings is bad for anyone’s mental health. Damp and mould bring respiratory problems and other illnesses. Those in poor, over- crowded housing suffered most in lockdown, and were more likely to catch and spread Covid. Having to move all the time is stressful and makes it much harder to build support networks. Mindy Fullilove, an American professor of urban policy and health, calls this phenomenon “root shock”, after the trauma a plant experiences when it is moved carelessly to shallow soil. The homeless people Lavelle speaks to struggle with three big problems: experience of abuse, mental illness, and drug and alcohol addiction. One reason that spice (a synthetic cannabinoid) is so popular on the streets and in hostels, Lavelle says, is that it makes time go quickly. He is open about his own problems. The victim in infancy of a family trauma that he can’t write about for legal reasons, he spent much of his childhood being excluded or expelled from school and attending special educational establishments. The psychiatrist who diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder when Lavelle was seven “didn’t need to strain his diagnostic skills too much”. He does not sound like the most compliant hostel dweller, getting into arguments with other residents and with the super- visor who, when Lavelle has the flu, refuses him Strepsils because they contain alcohol. At one point he punches a hole in a windscreen. “If being one’s own worst enemy was a sport, I’d be a Hall of Fame world champion”, he concedes. His point is that the people who end up in hostels and shelters are often JULY 22, 2022 hard to handle, but that this should not affect the support they receive. The NHS, after all, does not require character references before admitting you to A&E. Adequate housing is a human right, not a reward for good behaviour. Lavelle’s béte noire is what he calls “philanthro- capitalism”: the voluntary sector, charities and private companies that have taken over homeless provision in the age of austerity. These organizations are self-regulating because they provide “support” rather than “personal care”. They are not monitored by the Care Quality Commission or Ofsted, even though those they support may be as young as sixteen. Nor do they have to comply with Freedom of Information requests. They can ask hostel resi- dents to work for a meagre weekly allowance rather than the minimum wage, impose strict rules on their behaviour and evict them for minor breaches. Both Spratt and Lavelle advocate the Housing First model pioneered in the 1990s by Sam Tsem- beris, then a clinical psychologist at New York University. Housing First provides homeless people with their own home straightaway, with no precon- ditions. They are not required to move gradually up the ladder from a night shelter to more secure housing. They do not need to get a job first, or obey someone else’s house rules, or abstain from drugs and alcohol. Only when they have been housed are their other needs addressed. Tsemberis tells Lavelle that Housing First is more about providing treatment for addiction and mental health problems than about housing, but says “you can’t really talk about the treatment unless the person is housed, otherwise the whole conversation is only about survival”. Housing First has been successful in the American states and cities where it has been rolled out, as well as in Finland, the only EU country where homelessness is falling. These books argue convincingly that investing in more social housing would benefit everyone, not just those who live in it. It would ease pressure on the rental sector and make private landlords compete with an alternative source of good-quality and secure homes. It would take the heat out of the housing market and start to counter the inheritocracy in which older people sitting on equity pass it on to their children. It would alleviate other forms of injustice, since housing inequality falls disproportionately on Black, Asian and minority ethnic tenants. It would make the kind of housing TLS A rough sleeper’s belongings in an underpass in east London POLITICS safety scandal exposed by the Grenfell Tower fire less likely. And it would reduce homelessness, which places immense strain on the police, the criminal justice system, the NHS and councils. More subtly but profoundly, investing in social housing would soften, for millions of people, that repeated blow to their self-esteem that comes from being beholden to someone else. It is fatiguing and confidence-sapping to live with stained mattresses and broken shower curtains; to show potential buyers, your would-be evictors, around your home; to be fearful of provoking your landlord by making a fuss about repairs; to feel stuck in a limbo of enforced adolescence, waiting for grown-up life to begin. All this makes for what Spratt calls “an uneasy and constant refrain, your life sung to the tune of the privilege of others”. People waste hulking portions of their lives looking for rented rooms, dealing with bad landlords, extricating them- selves from nightmare house shares and moving their stuff from one room to the next. What could be achieved with all that energy if it were expended more creatively? Perhaps something is stirring. Spratt highlights the work of the community union ACORN and organizations such as Generation Rent and Safer Renting, which fight for tenants’ rights. She reports on eviction resistance bootcamps and renters fight- ing back against gentrifying regeneration schemes. In 2016 she fronted a successful campaign to get letting fees banned and deposits capped. Ultimately, though, her book leaves you with the sense that nothing much will change while the haves (home- owners and investors) outnumber the have-nots (renters and the homeless). Housing inequality has barely been mentioned in recent election campaigns. Spratt is told that when David Cameron was prime minister, the phrase “housing crisis” was banned in government. In the early 2010s, while working as a junior producer on Newsnight, she suggested covering more housing stories, but her editor - homeowning and privately educated - told her that they were “just not that interesting”. The same kind of willed obliviousness allows newspapers to place the blame for the housing crisis on immigrants, or on young people who are buying too many avocados or espressos to save for a deposit. In the face of such simplistic explanations, these books enrich our impoverished sociological imagination. Their case studies are as bleakly memorable as Raymond Carver stories. A Brighton man sleeps in his work van at the height of the pandemic, after losing his flat just before the second lockdown. A woman evicted from her flat in Peckham, who has recently attempted suicide, is told that if she does not accept a flat in Croydon she will have made herself “intentionally homeless” and forfeited any right to support. When she asks how she is meant to get to work or take her daughter to school, the placement officer tells her to “get up earlier”. Lavelle spends a wet and freezing November night wandering around Oldham, making endless circuits of the shopping centre until it closes and “laughing maniacally about what a parody my life had become”, before huddling underneath a bridge. Both books retell the story of Gyula Remes, the Hungarian national who, just before Christmas 2018, died in the underpass leading from the Houses of Parliament to Westminster Tube station. At forty- three, he was one year short of the mean age at death of a homeless person in England and Wales. This story received wide coverage because it seemed shocking that MPs could routinely walk past the effects of the austerity for which many of them had voted. But it is not really so shocking - because MPs are no different from the rest of us, we who avert our eyes from the daily disaster playing out in the pile of blankets on the other side of a pavement. These books succeed in reinserting a whole person into that human-shaped heap: someone with a name, a family, a life history that led them there and a body just as achy as ours would be if our bed were made of stone. = PHILOSOPHY Living in truth The philosopher who inspired resistance in communist Eastern Europe JAMES KRAPFL CONFRONTING TOTALITARIAN MINDS Jan Patocka on politics and dissidence ASPEN E. BRINTON 300pp. Karolinum Press. Paperback, £16. LIVING IN PROBLEMATICITY JAN PATOCKA Translated and edited by Eric Manton 84pp. Karolinum Press and OIKOYMENH with the Czech Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Philosophy. Paperback, £14. CARE FOR THE SOUL The selected writings of Jan Patocka JAN PATOCKA Translated by Alex Zucker with Andrea Rehberg and David Charlston Edited by Ivan Chvatik and Erin Plunkett 392pp. Bloomsbury Academic. Paperback, £22.49. wrote Vaclav Havel in The Power of the Powerless, “the spectre of what in the West is called ‘dissent’”. The dissident playwright’s revision of the first line of The Communist Manifesto was more than playful criticism; it gave expression to a philosophy of history that Havel hoped might supplant that of Marx and Engels, and even save the world from self-destruction. The author of this philosophy, well known in France and central Europe, but less familiar to anglophone readers, was the Czech phenomenologist Jan Patocka. Pato¢ka (1907-77) was a student of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, and a “partner” with Hannah Arendt, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and others in the enterprise of probing our subjective relationships to worldly phenomena. Appointed a professor at Charles University in 1936, he was able to teach formally for only a few years before and after the Second World War, and following the Prague Spring. He was never imprisoned, but the Nazis pressed him into manual labour and the communists restricted him to marginal academic positions. He was none- theless famous for his informal teaching and for the many writings in which he struggled with the question of how to live in history. It is tempting to explain Patocka’s importance instrumentally, tracing a causal trajectory from his underground seminars in Prague in the 1970s to the demise of communist regimes across Eastern Europe in 1989. This interpretation highlights Patocka’s influence on Havel and the dissident association they named after the year of its founding, Charter 77. Havel dedicated The Power of the Powerless to Patocka’s memory in 1978, and there is evidence that the essay inspired the founders of the Polish Solidarity movement in 1980. The revolutionary asso- ciations in which millions of Czechoslovak citizens participated in 1989-90 were directly modelled on Charter 77. Seen this way, Patocka’s idea of “the solidarity of the shaken” gave Solidarity and Czecho- slovakia’s own Velvet Revolution a blueprint for non-violent revolution. The books reviewed here do not dispute this inter- pretation, but their authors and editors insist that the value of Patoéka’s philosophy of history transcends its impact on history. For Patocka, Socratic question- ing - and not class conflict or revolution - is history’s locomotive. Dissidence inevitably results from such questioning, and in Confronting Totalitarian Minds: 10 (14 A SPECTRE IS HAUNTING Eastern Europe”, Jan Patocka on politics and dissidence, Aspen E. Brinton explains how it gives life meaning in other- wise hopeless situations. Two collections of Patocka’s writings, meanwhile, can be read as manuals for dis- sident practice. Living in Problematicity shows how he analysed historical events philosophically, from the interwar crisis of democracy to the normalization that followed the suppression of the Prague Spring in 1968. Care for the Soul: The selected writings of Jan Patocka presents essays on subjects ranging from history and philosophy to education and literature that together address the question of how to live meaningfully with others in historical time. History, for Patocka, is “the shaken certitude of pre-given meaning”. Brinton invokes Plato’s cave allegory to explain. The prisoner questions whether shadows on the cave wall comprise the full extent of reality; questioning enables him to leave the cave, but a sense of responsibility ultimately compels him back to help liberate those who remain. If he suc- ceeds, the community of questioners may constitute a polis, a space where the soul - that element of a human being not exhausted by the mere mainte- nance of life - can be cultivated. Patocka contrasts the history that results from questioning with a “prehistory” in which unquestioned myth provided meaning ready-made. This history is driven (albeit to no certain end- point) by those who practise “philosophy” in Patocka’s universally accessible sense - who “care for their souls” through the Socratic questioning of pre-given meaning. Care for the soul entails “living in truth” - a phrase that Havel made famous in The Power of the Powerless - though it does not pre- suppose any absolute truth. Patocka explicitly rejects Plato’s belief that we can achieve absolute truth, calling instead for “negative Platonism”. A more straightforward way of expressing the idea of “living in truth” might be “living in problematicity”: search- ing for a truth that can never be absolutely known. The problematicity of meaning is truthful in and of itself, and those who care for their souls accept their responsibility for whatever meaning they embrace in a world of uncertainty. One of the most arresting pieces in Care for the Soul, edited by Ivan Chvatik and Erin Plunkett, and translated by Alex Zucker with Andrea Rehberg and David Charlston, is “Limping Pilgrim Josef Capek”, a reflection on the life and death of the titular Czech painter. As Plunkett explains in her insightful TLS “Fantomas” by Josef Capek, 1918 66 Patocka gave Solidarity and Czechoslovakia’s own Velvet Revolution a blueprint for non-violent revolution James Krapfl is an associate professor of European history at McGill University. He is the author of Revolution with a Human Face: Politics, culture, and community in Czechoslovakia, 1989-1992, 2013 introduction, the essay presents authentic human life as a pilgrimage to an unknown place in which we limp between two impulses, “that which would bind us to the earth and the familiar, and that which leads us to strike out again and again into the unfamiliar”. Patocka offers another view of these impulses in “Life in Balance, Life in Amplitude”, which Eric Manton includes in Living in Problematicity. The former is a life of pragmatism, governed by the every- day; the latter is transcendence of the everyday. Through the questioning that is care for the soul, we can rise above the everyday - mere historicity - and find our meaning in history. The polis, once founded, never returns to a state of prehistory, but its citizens can revert to myth and a craving for the certain meanings that myth provides. Thus it is that, though leaving the cave made it possible to found the polis, the polis none- theless executed Socrates. As Manton stresses in his conclusion, “philosophy challenges the ideologies’ myths and dispels the illusions that society is led and comforted by”. The fate of Socrates threatens all “dissidents”. Yet some witnesses may be “shaken” by violent attempts to preserve pre-given meaning. If they establish a community with each other, this “solidarity of the shaken” can become a force in history, pushing humanity towards a polis where Socrates can live. It was this solidarity that Patocka hoped to nurture in joining Havel as one of Charter 77’s first spokes- men. Charter signatories expressed their sense of “co-responsibility” and sought “to conduct a con- structive dialogue” by drawing attention to the state’s violation of its own laws, in hopes of fostering a “humane society”. The cave-dwellers reacted pre- dictably and, though persecution in most cases stopped short of murder, Patocka, who had bronch- itis when called for questioning in March 1977, died of complications ten days later. The Velvet Revolution of 1989 again exemplified the solidarity of the shaken - this time uniting mil- lions of citizens shaken by violence against students calling for freedom in Prague. Yet even though the revolution created a polis where Socrates was far less likely to be killed, it was not a happily-ever-after story. As Havel had emphasized in The Power of the Powerless, techniques of manipulation in the West were “infinitely more subtle and refined than the brutal methods used in post-totalitarian societies”, and with the revolution Czechoslovakia rejoined the mainstream of what Patocka called “technological civilization”. Though made possible by Socratic questioning, this civilization places itself entirely in the service of the everyday, neglecting questions of human meaning. By reducing human beings to their roles, it forces them to live in falsehood. Mobilizing ever more force, it threatens humanity itself with destruction, whether through nuclear catastrophe or environmental degradation. Confronting Totalitarian Minds addresses those shaken by systemic violence in today’s world, what- ever form it may take. Brinton clearly explains key themes of Patocka’s philosophy before comparing his thought with that of other dissidents: Havel, the anti-Nazi theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Mahatma Gandhi, student and anti-atomic activists of the 1960s, and environmental activists today. The com- parisons are remarkably instructive. Bonhoeffer’s “religionless Christianity”, for example, resembles Patocka’s “negative Platonism” in its insistence on the inaccessibility of absolute truth, suggesting that similar approaches to living in problematicity can proceed from both Christian and secular starting points. Gandhi's life history shows “the general applicability of Patocka’s philosophy to all who turn to dissident politics as a way to move through life”, helping to overcome an unnecessary Eurocentrism in Pato¢ka’s oeuvre. Perhaps most importantly, Brinton stresses that dissidents must be ever open to questioning, rejecting absolutes, lest they suffer the consequences of hubris or, worse, their efforts result in new systems of oppression. The dissident path is by nature uncertain, but that is precisely what makes it the only path along which history can continue. = JULY 22, 2022 FINE ART IMAGES/HERITAGE IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES ©