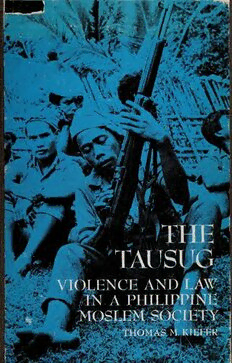

The Tausug: Violence and Law in a Philippine Moslem Society PDF

Preview The Tausug: Violence and Law in a Philippine Moslem Society

' . * €pr ?% nMiPiiF, i< ff: JS8 * * * ,'" mtw WwSsm ^1 V , yIMkj Vb^Hh !HHB alplil 1PHJ flrff j$PlP$!f 1§m| ir X ISpI 1 ■?. --^| rrffi iii^J^BBCrMi^B^K^Tnilr^i>ifMiii[iTfr'W#jMiritr''irii ^pgafapj i;«3 Hope Co. ■■‘Of- " O Holland, Mich. 49423 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/tausugviolencelaOOOOkief / 3"G CASE STUDIES IN CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY GENERAL EDITORS George and Louise Spindler STANFORD UNIVERSITY THE TAUSUG Violence and Law in a Philippine Moslem Society THE TAUSUG Violence and Law in a Philippine Moslem Society THOMAS M. KIEFER Brown University HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON, INC. NEW YORK CHICAGO SAN FRANCISCO ATLANTA DALLAS MONTREAL TORONTO LONDON SYDNEY Copyright <c) 1972 by Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc. All rights reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 77-179549 ISBN: 0-03-085618-3 Printed in the United States of America 23456 059 987654321 Foreword About the Series These case studies in cultural anthropology are designed to bring to students, in beginning and intermediate courses in the social sciences, insights into the rich¬ ness and complexity of human life as it is lived in different ways and in different places. They are written by men and women who have lived in the societies they write about and who are professionally trained as observers and interpreters of human behavior. The authors are also teachers, and in writing their books they have kept the students who will read them foremost in their minds. It is our belief that when an understanding of ways of life very different from one’s own is gained, abstractions and generalizations about social structure, cultural values, subsistence techniques, and the other universal categories of human social behavior become meaningful. About the Author Thomas M. Kiefer received his Ph.D. degree in anthropology from Indiana University in 1969. He also studied at Northwestern University and the University of Chicago. He has taught at the University of California at Berkeley. Interested in comparative law and the peoples of Southeast Asia, he is currently teaching at Brown University. He also teaches courses in ethnomusicology and film-making. About the Book This is a study of a cultural system where violence is an everyday occurrence, where nearly every dispute escalates to violence, but where there is no word for violence itself, as the word is understood in Western culture. Instead there is a Tausug word, maisug, "very masculine” or "very brave.” A maisug person is not deterred by physical danger or risk; he expresses emotions; he is combative, always ready to respond with quick anger to every real or imagined insult or injury to himself or his close kin. Violence in all societies is paradoxical, and it is indeed so among the Tausug. They do not teach their children to fight. They teach them not to fight. Violence itself, however it is expressed, is considered morally wrong by the Tausug. To be shamed without taking revenge is, however, as great a wrong. Both the denial of violence and the sanctions for it exist together simultaneously. The Tausug recog- vi • FOREWORD nize that man cannot be entirely consistent in either his behavior or his thinking, for there is the real world of man and the world of God. What is morally wrong in the latter may be unavoidable in the former. The author of this case study describes the forms that violence among the Tausug takes and the conditions that trigger it. He analyzes the manner in which the defense of interests and restoration of honor may occur, when either interests or honor have been threatened or damaged. He goes further to show how disputes and the violent feuds they flare into are social processes, ramifying throughout the social system. Violence is an expression of these relationships and at the same time is contained within them and limited by them. Violence does not occur in a social vacuum, among the Tausug or in our own society. But for the Tausug the environ¬ ment of violence is personal, so violence, its escalation, and its resolution are mean¬ ingful expressions of both personal feelings and of the social structure. The resolution of violence and the settlement of disputes do not occur solely through the personalized feud among the Tausug. The idea and the practice of law are well developed. Tausug life has a strongly legalistic turn. The people are as obsessed with litigation as they are with the conflicts which make it necessary. This case study of the Tausug also includes an analysis of their religion—a mixture of Islam, or at least a folk version of it, surviving ritual and belief from premodern times, and reworkings of orthodox Moslem ideas into new and unique patterns. The case study ends with a discussion of present relationships between the Tausug and the Philippine government. The gulf between the two is wide because of religious differences and because the Tausug, like the other Moslem groups around the Sula Sea, have been fiercely independent and intractable. The unofficial goal of the Philippine government appears to be the obliteration of Tausug culture. However understandable as a reflex to an aggressively independent and intractable minority within a national whole already faced with serious prob¬ lems of factionalism, this is deeply regrettable. The Tausug, like many other minor¬ ities, is threatened with ethnocide. Whatever the eventual outcome of the struggle between the national government and the Tausug and other peoples like them, the future path of the Tausug will not be a smooth one. George and Louise Spindler General Editors Stanford, Calif.