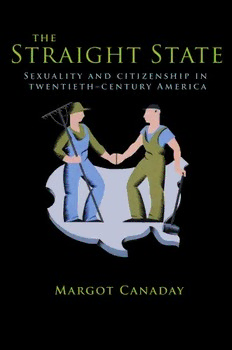

The Straight State:Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America PDF

Preview The Straight State:Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America

This content downloaded from 129.64.99.141 on Fri, 16 Nov 2018 06:55:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Straight State ! This content downloaded from 129.64.99.141 on Fri, 16 Nov 2018 06:55:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms POLITICS AND SOCIETYIN TWENTIETH-CENTURYAMERICA SERIES EDITORS William Chafe, Gary Gerstle, Linda Gordon, and Julian Zelizer Alist of titles in this series appears at the back of the book This content downloaded from 129.64.99.141 on Fri, 16 Nov 2018 06:55:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Straight State ! SEXUALITY AND CITIZENSHIP IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICA Margot Canaday PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD This content downloaded from 129.64.99.141 on Fri, 16 Nov 2018 06:55:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Copyright © 2009 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Canaday, Margot. The straight state : sexuality and citizenship in twentieth-century America / Margot Canaday. p. cm. — (Politics and society in twentieth-century America) Includes index. ISBN 978-0-691-13598-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Homosexuality—United States—History—20th century. 2. Homosexuality—Political aspects— United States—History—20th century. 3. United States— Social policy—1980-1993. 4. Political rights— United States—History—20th century. I. Title. HQ75.16.U6C36 2009 323.3!2640973—dc22 2008041020 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Palatino Printed on acid-free paper. ! press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 This content downloaded from 129.64.99.141 on Fri, 16 Nov 2018 06:55:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms For Rachel This content downloaded from 129.64.99.141 on Fri, 16 Nov 2018 06:55:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Contents ! List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 PARTI: Nascent Policing 1. IMMIGRATION “ANew Species of Undesirable Immigrant”: Perverse Aliens and the Limits of the Law, 1900–1924 19 2. MILITARY “We Are Merely Concerned with the Fact ofSodomy”: Managing Sexual Stigma in the World War I–Era Military, 1917–1933 55 3. WELFARE “Most Fags Are Floaters”: The Problem of “Unattached Persons” during the Early New Deal, 1933–1935 91 PARTII: Explicit Regulation 4. WELFARE “With the Ugly Word Written across It”: Homo-Hetero Binarism, Federal Welfare Policy, and the 1944 GI Bill 137 5. MILITARY “Finding a Home in the Army”: Women’s Integration, Homosexual Tendencies, and the Cold War Military, 1947–1959 174 6. IMMIGRATION “Who Is a Homosexual?”: The Consolidation of Sexual Identities in Mid-twentieth-century Immigration Law, 1952–1983 214 Conclusion 255 Index 265 This content downloaded from 129.64.99.141 on Fri, 16 Nov 2018 06:57:16 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Illustrations ! “Another Emergency Project,” Saturday Evening Post 209 (February15, 1937) 28 Screening soldiers (as well as immigrants) brought sex/gender difference to the attention of federal officials 63 Transients at work setting up a Pennsylvania camp 104 An example of the homoerotic content that was common in transient newspapers 111 “Ex-Serviceman Seeks Answers” 157 Psychiatrist Marion Kenworthy training officers on recruit selection methods at the WAC Training Center at Fort Lee inVirginia 182 This content downloaded from 129.64.99.141 on Fri, 16 Nov 2018 06:55:16 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Acknowledgments ! I once told a colleague that I decided to become an academic because I wanted to surround myself with smart and unconventional people. She snorted in response, but it really wasn’t such a bad call. As I have worked on this project, I have been continually delighted by the wealth of (smart and unconventional) people who have taken time to encour- age, mentor, and even offer me their friendship. They have been critical to my development as a historian, and it is my pleasure to be able to thank them here. This book began as a dissertation at the University of Minnesota, where I was incredibly fortunate to get my own start as well. At Min- nesota, I benefited greatly from being in a history department that was not only intellectually dynamic, but also held up feminism, democracy, and kindness to graduate students as core principles. I know that long before I arrived on the scene, my co-adviser Sara Evans played a criti- cal role in imprinting those values on the department, and I thank her especially for creating an environment in which so many of us would thrive. She was, along with co-adviser Barbara Welke, an exquisite men- tor, and I thank them both for their distinct but complementary guid- ance during my years as a graduate student. Elaine Tyler May was es- sentially a third adviser to the dissertation, and I am grateful for all her generosity and insight. Sally Kenney, Erika Lee, and Kevin Murphy also served on my committee, read dissertation chapters, provided research advice, and moral support. Anna Clark, Mary Dietz, and Lisa Disch each made critical contributions to my graduate education. I also want to thank my friends in American studies (Kim Heikkila, Kate Kane, and Mary Strunk) for inviting me into their terrific dissertation group. I thank as well members of the Comparative Women’s History Work- shop and those in Elaine and Lary May’s dissertation group for their many thoughtful critiques. The next stop was (and still is) Princeton University, where a postdoc- toral fellowship in the Society of Fellows has provided me ample time to write and think. I thank Leonard Barkan, Mary Harper, Carol Rigolot, and Michael Wood for creating the ideal conditions under which to write a book. Graham Jones, Mendi Obadike, Miriam Petty, Sarah Ross, Jennifer Rubenstein, and Gayle Salamon kept a bit of adolescence alive on the second floor of the Joseph Henry House, and I thank them and all the fellows for their camaraderie. I am also grateful for the warm This content downloaded from 129.64.99.141 on Fri, 16 Nov 2018 06:55:18 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms xii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS welcome from many wonderful colleagues in the history department— Jeremy Adelman, Janet Chen, Angela Creager, Ben Elman,Shel Garon, Michael Gordin, Tony Grafton, Molly Greene, Josh Guild, Judy Hanson, Tera Hunter, Bill Jordan, Kevin Kruse, Michael Laffan, Phil Nord, Bar- bara Oberg, Bhavani Raman, Dan Rodgers, Chris Stansell, Helen Tilley, Sean Wilentz, Julian Zelizer, and most especially Dirk Hartog, who has been my friend in New Jersey from day one. Beyond Minnesota or Princeton, I have been extremely fortunate to be able to count on the support and mentoring of those more experi- enced than I. For their kind words and generous deeds over many years, I thank especially Susan Cahn, John D’Emilio, Linda Kerber, Re- gina Kunzel, Laura McEnaney, Joanne Meyerowitz, Sonya Michel, and Chris Tomlins. More generally, I want to acknowledge a broader com- munity of queer historians and a broader community of legal historians for their respective commitments to nurturing young scholars. In a re- lated but slightly distinct category, Pippa Holloway has been the most steadfast of professional companions and my favorite person to play hooky with at annual meetings. In innumerable ways, she has helped me to keep joy firmly centered in my professional life. (And talk about smart and unconventional!) My relationship with Barbara Welke now transcends any institutional tie (and also merits its own paragraph). Barbara was an amazingly giv- ing dissertation adviser, but her support and friendship have meant even more to me in the years since graduate school. She reads everything I write (often multiple times) and consistently asks questions that make me think about my work in bigger ways. She has fielded questions from me on every imaginable topic. I call her when things go well, and I call her when they don’t. Her unwavering belief in me and my work has given me a confidence that I doubt otherwise I would have. Above all, I appreciate her skepticism about the things in our profession that don’t really matter, as well as her optimism about the things that do. This book is far better because of those who read it and told me how to improve it. Individual chapters were read by Mary Anne Case, Andrea Friedman, Sandy Levitsky, Sonya Michel, Kevin Murphy, Chris Stansell, members of the Gender and Sexuality Studies Workshop at the Univer- sity of Chicago, members of the Modern America Workshop at Princeton University, fellows at the Hurst Institute in Legal History at the Univer- sity of Wisconsin, and participants at the annual retreat of the Program in Law and Public Affairs at Princeton University. Brian Balogh, Nancy Cott, John D’Emilio, Gary Gerstle, Linda Gordon, Dirk Hartog, Beth Hill- man, Linda Kerber, Kate Masur, Joanne Meyerowitz, Bethany Moreton, Claire Potter, Rachel Spector, and Barbara Welke read the entire manu- script (at various stages). All of you were vitally important. Thank you. This content downloaded from 129.64.99.141 on Fri, 16 Nov 2018 06:55:18 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms