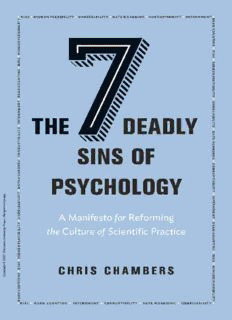

The Seven Deadly Sins of Psychology: A Manifesto for Reforming the Culture of Scientific Practice PDF

Preview The Seven Deadly Sins of Psychology: A Manifesto for Reforming the Culture of Scientific Practice

.d e vre se r sth g ir llA .sse rP ytisre vin U n o te cn irP .7 1 0 2 © th g iryp o C THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS OF PSYCHOLOGY .d e vre se r sth g ir llA .sse rP ytisre vin U n o te cn irP .7 1 0 2 © th g iryp o C .d e vre se r sth g ir llA .sse rP ytisre vin U n o te cn irP .7 1 0 2 © th g iryp o C THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS OF PSYCHOLOGY A Manifesto for Reforming the Culture of Scientific Practice CHRIS CHAMBERS .d e vre se r sth gir llA Princeton University Press .sse Princeton & Oxford rP ytisre vin U n o te cn irP .7 1 0 2 © th g iryp o C CONTENTS Preface ix Chapter 1. The Sin of Bias 1 A Brief History of the “Yes Man” 4 Neophilia: When the Positive and New Trumps the Negative but True 8 Replicating Concepts Instead of Experiments 13 Reinventing History 16 The Battle against Bias 20 Chapter 2. The Sin of Hidden Flexibility 22 p- Hacking 24 Peculiar Patterns of p 29 Ghost Hunting 34 Unconscious Analytic “Tuning” 35 Biased Debugging 39 Are Research Psychologists Just Poorly Paid Lawyers? 40 Solutions to Hidden Flexibility 41 Chapter 3. The Sin of Unreliability 46 Sources of Unreliability in Psychology 48 .d evre Reason 1: Disregard for Direct Replication 48 se Reason 2: Lack of Power 55 r sthg Reason 3: Failure to Disclose Methods 61 ir llA .sserP RReeaassoonn 45:: FSatailtuisrtei ctaol RFeatllraaccite s 6653 ytisre Solutions to Unreliability 67 vin U n Chapter 4. The Sin of Data Hoarding 75 o te cn The Untold Benefits of Data Sharing 77 irP .7 Failure to Share 78 1 0 2 © Secret Sharing 80 th g How Failing to Share Hides Misconduct 81 iryp oC Making Data Sharing the Norm 84 Grassroots, Carrots, and Sticks 88 viii | Contents Unlocking the Black Box 91 Preventing Bad Habits 94 Chapter 5. The Sin of Corruptibility 96 The Anatomy of Fraud 99 The Thin Gray Line 105 When Junior Scientists Go Astray 112 Kate’s Story 117 The Dirty Dozen: How to Get Away with Fraud 122 Chapter 6. The Sin of Internment 126 The Basics of Open Access Publishing 128 Why Do Psychologists Support Barrier- Based Publishing? 129 Hybrid OA as Both a Solution and a Problem 132 Calling in the Guerrillas 136 Counterarguments 138 An Open Road 147 Chapter 7. The Sin of Bean Counting 149 Roads to Nowhere 151 Impact Factors and Modern- Day Astrology 151 Wagging the Dog 160 The Murky Mess of Academic Authorship 163 Roads to Somewhere 168 Chapter 8. Redemption 171 .d e Solving the Sins of Bias and Hidden Flexibility 174 vre se Registered Reports: A Vaccine against Bias 174 r sthg Preregistration without Peer Review 196 ir llA .sserP SSoollvviinngg tthhee SSiinn ooff UDnatrae lHiaobailridtyin g 219082 ytisre Solving the Sin of Corruptibility 205 vin Solving the Sin of Internment 208 U n ote Solving the Sin of Bean Counting 210 cn irP Concrete Steps for Reform 213 .7 10 Coda 215 2 © th g iryp Notes 219 o C Index 263 PREFACE This book is borne out of what I can only describe as a deep personal frus- tration with the working culture of psychological science. I have always thought of our professional culture as a castle—a sanctuary of endeavor built long ago by our forebears. Like any home it needs constant care and atten- tion, but instead of repairing it as we go we have allowed it to fall into a state of disrepair. The windows are dirty and opaque. The roof is leaking and won’t keep out the rain for much longer. Monsters live in the dungeon. Despite its many flaws, the castle has served me well. It sheltered me during my formative years as a junior researcher and advanced me to a position where I can now talk openly about the need for renovation. And I stress renovation because I am not suggesting we demolish our stronghold and start over. The foundations of psychology are solid, and the field has a proud legacy of discovery. Our founders—Helmholtz, Wundt, James— built it to last. After spending fifteen years in psychology and its cousin, cognitive neu- roscience, I have nevertheless reached an unsettling conclusion. If we con- tinue as we are then psychology will diminish as a reputable science and could very well disappear. If we ignore the warning signs now, then in a .de hundred years or less, psychology may be regarded as one in a long line of vre se quaint scholarly indulgences, much as we now regard alchemy or phrenol- r sthg ogy. Our descendants will smile tolerantly at this pocket of academic antiq- ir llA uity, nod sagely to one another about the protoscience that was psychology, .sserP and conclude that we were subject to the “limitations of the time.” Of ytisre course, few sciences are likely to withstand the judgment of history, but it vin is by our research practices rather than our discoveries that psychology will U n ote be judged most harshly. And that judgment will be this: like so many other cn irP “soft” sciences, we found ourselves trapped within a culture where the ap- .7 10 pearance of science was seen as an appropriate replacement for the practice 2 © th of science. g iryp In this book I’m going to show how this distortion penetrates many as- o C pects of our professional lives as scientists. The journey will be grim in x | Preface places. Using the seven deadly sins as a metaphor, I will explain how un- checked bias fools us into seeing what we want to see; how we have turned our backs on fundamental principles of the scientific method; how we treat the data we acquire as personal property rather than a public resource; how we permit academic fraud to cause untold damage to the most vulnerable members of our community; how we waste public resources on outdated forms of publishing; and how, in assessing the value of science and scien- tists, we have surrendered expert judgment to superficial bean counting. I will hope to convince you that in the quest for genuine understanding, we must be unflinching in recognizing these failings and relentless in fixing them. Within each chapter, and in a separate final chapter, I will recommend various reforms that highlight two core aspects of science: transparency and reproducibility. To survive in the twenty- first century and beyond we must transform our secretive and fragile culture into a truly open and rigor- ous science—one that celebrates openness as much as it appreciates innova- tion, that prizes robustness as much as novelty. We must recognize that the old way of doing things is no longer fit for purpose and find a new path. At its broadest level this book is intended for anyone who is interested in the practice and culture of science. Even those with no specific interest in psychology have reasons to care about the problems we face. Malpractice in any field wastes precious public funding by pursuing lines of enquiry that may turn out to be misleading or bogus. For example, by suppressing certain types of results from the published record, we risk introducing ineffective .d e clinical treatments for mental health conditions such as depression and vre se schizophrenia. In the UK, where the socioeconomic impact of research is r sthg measured as part of a regular national exercise called the Research Excel- ir llA .sserP lwenidcee rFarnagmee owf orreka l(-R wEoFrl)d, paspypclhicoaltoigoyn sh. aTsh ael s2o0 b1e4e Rn EsFh orwepno trote idn flouveern c4e5 0a ytisre “impact case studies” where psychological research has shaped public policy vin or practice, including (to name just a few) the design and uptake of electric U n ote cars, strategies for minimizing exam anxiety, the development of improved cn irP police interviewing techniques that account for the limits of human mem- .7 10 ory, setting of urban speed limits based on discoveries in vision science, 2 © th human factors that are important for effective space exploration, govern- g iryp ment strategies for dealing with climate change that take into account pub- o C lic perception of risk, and plain packaging of tobacco products.1 From its Preface | xi most basic roots to its most applied branches, psychology is a rich part of public life and a key to understanding many global problems; therefore the deadly sins discussed here are a problem for society as a whole. Some of the content, particularly sections on statistical methods, will be most relevant to the recently embarked researcher—the undergraduate stu- dent, PhD student, or early- career scientist—but there are also important messages throughout the book for more senior academics who manage their own laboratories or institutions, and many issues are also relevant to jour- nalists and science writers. To aid the accessibility of source material for different audiences I have referred as much as possible to open access litera- ture. For articles that are not open access, a Google Scholar search of the article title will often reveal a freely available electronic copy. I have also drawn on more contemporary forms of communication, including freely available blog entries and social media. I owe a great debt to many friends, academic colleagues, journal editors, science writers, journalists, press officers, and policy experts, for years of inspiration, critical discussions, arguments, and in some cases interviews that fed into this work, including: Rachel Adams, Chris Allen, Micah Allen, Adam Aron, Vaughan Bell, Sven Bestmann, Ananyo Bhattacharya, Dorothy Bishop, Fred Boy, Todd Braver, Björn Brembs, Jon Brock, Jon Butterworth, Kate Button, Iain Chalmers, David Colquhoun, Molly Crockett, Stephen Curry, Helen Czerski, Zoltan Dienes, the late Jon Driver, Malte Elson, Alex Etz, John Evans, Eva Feredoes, Matt Field, Agneta Fischer, Birte Forstmann, Fiona Fox, Andrew Gelman, Tom Hardwicke, Chris Hartgerink, Tom Hart- .d e ley, Mark Haselgrove, Steven Hill, Alex Holcombe, Aidan Horner, Macartan vre se Humphreys, Hans Ijzerman, Helen Jamieson, Alok Jha, Gabi Jiga- Boy, Ben r sthg Johnson, Rogier Kievit, James Kilner, Daniël Lakens, Natalia Lawrence, ir llA .sserP KSuesitahn LMawichs,i eK, aCtaien dMicaec kM, oLreeayh, R Micahiazredy ,M Jaosroeny, MSimatotinn gMleoys,s R, Roobs Ms McIonutnosche,, ytisre Nils Mulhert, Kevin Murphy, Suresh Muthukumaraswamy, Bas Neggers, vin Neuroskeptic, Kia Nobre, Dave Nussbaum, Hans Op de Beeck, Ivan Oran- U n ote sky, Damian Pattinson, Andrew Przybylski, James Randerson, Geraint Rees, cn irP Ged Ridgway, Robert Rosenthal, Pia Rotshtein, Jeff Rouder, Elena Rusconi, .7 10 Adam Rutherford, Chris Said, Ayse Saygin, Anne Scheel, Sam Schwarzkopf, 2 © th Sophie Scott, Dan Simons, Jon Simons, Uri Simonsohn, Sanjay Srivastava, g iryp Mark Stokes, Petroc Sumner, Mike Taylor, Jon Tennant, Eric Turner, Carien o C van Reekum, Simine Vazire, Essi Viding, Solveiga Vivian- Griffiths, Matt xii | Preface Wall, Tony Weidberg, Robert West, Jelte Wicherts, Ed Wilding, Andrew Wilson, Tal Yarkoni, Ed Yong, and Rolf Zwaan. Sincere thanks go to Sergio Della Sala and Toby Charkin for their collaboration and fortitude in cham- pioning Registered Reports at Cortex, Brian Nosek, David Mellor, and Sara Bowman for providing Registered Reports with such a welcoming home at the Center for Open Science, and to the Royal Society, particularly pub- lisher Phil Hurst and publishing director Stuart Taylor, for embracing Reg- istered Reports long before any other multidisciplinary journal. I also owe a debt of gratitude to Marcus Munafò for joining me in promoting Regis- tered Reports at every turn, and to the 83 scientists who signed our Guard- ian open letter calling for installation of the format within all life science journals. Finally, I extend a special thanks to Dorothy Bishop, the late (and much missed) Alex Danchev, Dee Danchev, Zoltan Dienes, Pete Etchells, Hal Pashler, Frederick Verbruggen, and E. J. Wagenmakers for extensive draft reading and discussion, to Anastasiya Tarasenko for creating the chap- ter illustrations, and to my editors Sarah Caro and Eric Schwartz for their patience and sage advice throughout this journey. .d e vre se r sth g ir llA .sse rP ytisre vin U n o te cn irP .7 1 0 2 © th g iryp o C

Description: