The Rosa Luxemburg Reader PDF

Preview The Rosa Luxemburg Reader

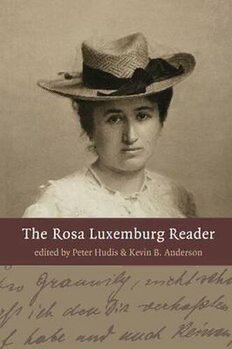

The Rosa Luxemburg Reader The Rosa Luxemburg Reader Edited by PETER HUDIS and KEVIN B. ANDERSON MONTHLY REVIEW PRESS New York Copyright©2004h} MONTHLY REVIEW PRESS All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the publisher ISBN I-58367-103-x (paperback) ISBN I-58367-104-8 (cloth) MONTHLY REVIEW PRESS 122 West 27th Street NewYork,NY 10001 www.monthlyreview.org Printed in Canada 10 g 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 I CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Peter Hudis and Kevin B. Anderson ............................ 7 PART o NE: Political Economy, Imperialism, and Non-Western Societies 1. The Historical Conditions of Accumulation, from The Accumulation of Capital ... 32 2. The Dissolution of Primitive Communism: From the Ancient Germans and the Incas to India, Russia, and Southern Africa, from Introduction to Political Economy .............................................................. 71 3. Slavery .......................................................................... 111 4. Martinique ...................................................................... 123 PART TWO: The Politics of Revolution: Critique of Reformism, Theory of the Mass Strike, Writings on Women 5. Social Reform or Revolution ..................................................... 128 6. The Mass Strike, the Political Party, and the Trade Unions ....................... 168 7. Address to the Fifth Congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party .... 200 8. Theory and Practice ............................................................. 208 g. Writings on Women, 1902-14: a) A Tactical Question .......................................................... 233 b) Address to the International Socialist Women's Conference .................. 236 c) Women's Suffrage and Class Struggle ......................................... 237 d) The Proletarian Woman ...................................................... 242 PART THREE: Spontaneity, Organization, and Democracy in the Disputes with Lenin 10. Organizational Questions of Russian Social Democracy ......................... 248 11. Credo: On the State of Russian Social Democracy .............................. 266 12. The Russian Revolution ......................................................... 281 PART FOUR: From Opposition to World War to the Actuality of Revolution 13. The Junius Pamphlet: The Crisis in German Social Democracy .................. 312 14. Speeches and Letters on War and Revolution, 1918-19 a) The Beginning ............................................................... 342 b) The Socialization of Society .................................................. 346 c) What Does the Spartacus League Want? ...................................... 349 d) Our Program and the Political Situation ...................................... 357 e) Order Reigns in Berlin ....................................................... 373 PART FIVE: "Like a Clap of Thunder" 15. Selected Correspondence, 1899-1917 ........................................... 380 NOTES ............................................................................ 396 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................... 431 INDEX ............................................................................ 433 Introduction By Peter Hudis and Kevin B. Anderson On January 12, 2003, over 100,000 people attended a rally in the Berlin sub urb of Friedrichsfelde to commemorate the life and legacy of Rosa Luxem burg and Karl Liebknecht. It may come as a surprise that so many turned out to commemorate these figures, who had been murdered by proto-fascist forces eighty-four years earlier. Yet the turnout was not completely unexpect ed, since it occurred in the midst of growing opposition around the world to the new stage of military intervention signaled by the impending U.S. invasion of Iraq. Luxemburg and Liebknecht were among the most impor tant antimilitarist figures in European history, and it is a testament to their enduring legacy that so many continue view them as a rallying point amid the challenges of imperialist war and terrorism. The legacy of Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919) extends far beyond her contri bution as an antimilitarist, however. Her life and work also speak to the search for a liberating alternative to the globalization of capital. More than any other Marxist of her generation, Luxemburg theorized capitalism's incessant drive for self-expansion, focusing especially on its destructive impact upon the tech nologically underdeveloped world. Her critique of capital's drive to destroy non-capitalist environments and her fervent opposition to imperialist expan sion has taken on new importance in light of the emergence of a new genera tion of activists and thinkers opposed to globalized capital. At the same time, her intense opposition to reformist compromise, bureaucratic intrigue, and elitist organizational methods speaks to the search for an anticapitalist alterna tive that avoids the repressive and hierarchical formations that have defined radical movements and efforts to create socialist societies over the past hun dred years. Her insistence on the need for revolutionary democracy after the seizure of power addresses some of the major unanswered questions of our time, such as: Is there an alternative to capitalism? Is it possible to stop global capital's drive for self-expansion without reproducing the horrors of bureau cracy and totalitarianism? Can humanity be free in an era defined by global ized capitalism and terrorism? Finally, her position as a woman leader and 7 8 THE ROSA LUXEMBURG READER theoretician in a largely male-dominated socialist movement has prompted some new reflections on gender and revolution. This Reader shows the full range of Luxemburg's contributions by includ ing for the first time in one volume substantial extracts from both her economic and political writings. Several key texts, here translated into English for the first time, deal with 1) the impact of capitalist globalization on precapitalist commu nal forms of social organization, 2) women's emancipation as an integral dimension of socialist transformation, and 3) critiques of the hierarchical orga nizational methods that have defined so much of the history of Marxism. Final ly, our selections from her correspondence attempt to convey her humanism and depth of vision. As a whole, this Reader aims to provide a resource for those trying to rethink the problems of radical social transformation today. I Rosa Luxemburg was one of the most original characters ever to participate in the socialist movement. Born on March 5, 1871, to a Jewish family in Zamosc, in the Russian-occupied part of Poland, she joined the revolution ary movement as a teenager, becoming active with Proletariat, one of the first organizations of Polish Marxists. She was smuggled out of Poland in 1889 when the group was crushed by government forces. She attended the Univer sity of Zurich from 1889 to 1897, where she wrote a doctoral dissertation enti tled The Industrial Development of Poland. Her activity in Polish revolutionary emigre circles in Switzerland and France in the early and mid- 189os already displayed the characteristics of political independence and theoretical assertiveness for which she later became renowned. In 1893 she attended the Third Congress of the Second International in Zurich, where she encountered such luminaries as Frederick Engels and Georgi Plekhanov, the founder of Russian Marxism. She argued against national self-determina tion for Poland, insisting instead on "strict" proletarian internationalism-a position that placed her in direct opposition to the most prominent socialist figures of the time, as well as to Marx's own writings on Poland. It was also in Zurich, in 1890, that Luxemburg met the Polish revolution ary Leo Jogiches (1867-1919), who became her comrade and lover for the next seventeen years, and remained a close colleague until the end of her life. Jogiches, who joined the socialist movement in Vilna in 1885, was an out standing strategist and organizer in the Polish, the Russian, and later the Ger man, revolutionary movements. He worked closely with Luxemburg on INTRODUCTION 9 many fronts, from offering constructive commentary on drafts of her articles and essays to propagating their ideas through tireless behind-the-scenes organizational work in the revolutionary underground. As the Luxemburg scholar Felix Tych has noted, the importance ofjogiches' contributions have tended to be underestimated, in part because he published little under his own name.1 Yet he too was an original character. Luxemburg's close friend, the socialist feminist Clara Zetkin, once noted that Jogiches "was one of those very masculine personalities-an extremely rare phenomenon these days-who can tolerate a great female personality."2 The passionate and stormy relationship between Luxemburg andjogiches, both during and after their period of intimacy, reveals much about Luxemburg as woman, as thinker, and as revolutionary. As she once noted, "I cleave to the idea that a woman's character doesn't show itself when love begins, but when it ends.":l Luxemburg's independent character came fully to the fore upon her move to Germany in 1898, where she became active in the German Social Democ ratic Party (SPD), then the largest socialist organization in the world. As a Polish-Jewish woman, she encountered considerable resentment and oppo sition from many party leaders, who referred to her in terms of a "guest who comes to us and spits in our parlor."4 Undeterred by such obstacles, she plunged directly into one of the most important disputes of the day, over Eduard Bernstein's effort to "revise" Marxism. At the time Bernstein was one of the leading figures in Marxism; Engels had designated him as his literary executor. It therefore came as a shock to see Bern stein argue in a series of articles in 1896-98 that the central theses of Marx's work were now out of date. Bernstein wrote that Marx's predictions about the inevitable breakdown and collapse of capitalism were no longer borne out by experience, as seen in the decreasing frequency of economic crises. He argued that the formation of the credit system, trusts, and monopolies showed that the "anarchy" of the capitalist market was being overcome and that capitalism was moving on its own towards "socialized" production. Bernstein also contended that the ability of trade unions to obtain higher wages would eventually sup press the rate of profit to the point where capitalist exploitation would come to an end without the need for a social revolution. He based his views on political as much as economic considerations. Bernstein argued that the growing power of Social Democracy, with the SPD having become a mass party with millions of members and supporters, showed that the capitalist order was capable of reform through legal and parliamentary means. He concluded, "For me the movement is everything, the goal is nothing."