The perverse art of reading : on the phantasmatic semiology in Roland Barthes' Cours au Collège de France PDF

Preview The perverse art of reading : on the phantasmatic semiology in Roland Barthes' Cours au Collège de France

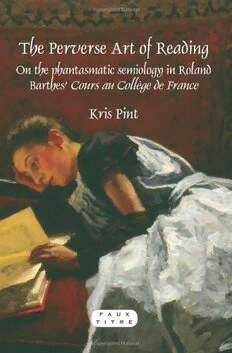

The Perverse Art of Reading On the phantasmatic semiology in Roland Barthes’ Cours au Collège de France FAUX TITRE 353 Etudes de langue et littérature françaises publiées sous la direction de Keith Busby, †M.J. Freeman, Sjef Houppermans et Paul Pelckmans The Perverse Art of Reading On the phantasmatic semiology in Roland Barthes’ Cours au Collège de France Kris Pint Translator Christopher M. Gemerchak AMSTERDAM - NEW YORK, NY 2010 Cover painting: W.B. Tholen, De zusters Arntzenius (1895), Collectie museumgoudA, Gouda. Photography: Tom Haartsen. Cover design: Pier Post. The paper on which this book is printed meets the requirements of ‘ISO 9706: 1994, Information and documentation - Paper for documents - Requirements for permanence’. Le papier sur lequel le présent ouvrage est imprimé remplit les prescriptions de ‘ISO 9706: 1994, Information et documentation - Papier pour documents - Prescriptions pour la permanence’. ISBN: 978-90-420-3092-3 E-Book ISBN: 978-90-420-3093-0 © Editions Rodopi B.V., Amsterdam - New York, NY 2010 Printed in The Netherlands Table of Contents Acknowledgments 7 Introduction 9 The Fantasy: A Psychoanalytic Intertext 31 The Fantasy: A Nietzschean Intertext 69 A Reader Writes Oneself 133 A Reader at the Collège de France 163 Elements of an Active Semiology: Space, Detail, Time and the Author 195 Lessons from an Amateur 257 Works Cited 277 Index 285 Acknowledgments Writing is a lonely job, but there are a lot of people without whose support—financially, intellectually, emotionally—this book would have remained unwritten. First of all, I would like to thank the colleagues, the students and the staff of both the department of Dutch Literature and Literary Theory at Ghent University and the Department of Arts and Architec- ture at the PHL University College for creating just the kind of envi- ronment which enabled me to read, to think aloud and to write. Special thanks should go to Jürgen Pieters for the valuable, in- spiring discussions which allowed me to create my own Barthesian cartography, with its necessary detours and side-paths. And thanks most of all to Nadia Sels, always my first reader, who kept me company on this ongoing journey for quite some time now. I want to dedicate this book to her. Kafka’s last diary entry, June 12, 1923: Every word, twisted in the hands of the spirits—thi s twist of the hand is their characteristic gesture—becomes a spear tur ned against the speaker. Most especially a remark like this. And so ad infinitum. The only consolation would be: it happens whether you l ike or not. And what you like is of infinitesimally little help. Mo re than consolation is: You too have weapons. (Kafka 1988, 423) Introduction A painting of girls, reading While the birthday greetings on the back of the picture postcard were not addressed to me, the painting portrayed on the front certainly seemed to be: The Arntzenius Sisters, painted in 1895 by a Dutch landscape artist whom I had never heard of, W.B. Tholen. The paint- ing depicts two girls perched together on a chaise longue, each of them engrossed in their reading. The one girl is sitting upright, her eyes glancing downward at the book in her lap that she grips with one hand, her other hand resting on the page. The other girl is reclining, her knees tucked up under her skirt, resting her head on her hand. She is poised to turn a page but forgets to do so, absorbed by what she is reading. Light streams inside from an unseen window behind the girls, noticeable only by the shine on the dark wood of the chair and the pale glow of the paper where letters are suggested by little dark patches of paint. Although it was not my birthday, I had to have the postcard. I would often return to it, just sit and stare at it without being able to uncover the secret of its mysterious attraction. At best I could localise my fascination in the dreamy, unflinching gaze of the second girl, lost in a world evoked by words that would remain forever unreadable for me. In other words, what my gaze latched onto was that which I can- not see in her gaze: the image of what she is reading, an image that gives her eyes that characteristic, impenetrable expression of someone daydreaming, unaware of her surroundings or even the words in the book she is holding. In her gaze I recognize the same intensity that rivets me as a reader to the page, and imprisons me for hours in an imaginary world. The picture postcard lied on my desk, was sometimes used as a bookmark, got lost and reappeared again, and the more I looked at the print, the more I became convinced that she coalesced the essence of our relation to the literary imagination; but at the same time I real- 10 The Perverse Art of Reading ised that this imagination was not going to yield her secret straight away. And then I recognized the same fascination for the strange rela- tionship between the reader’s imagination and the text in the work of ‘late’ Barthes, and in particular the courses he gave as professor of lit- erary semiology from 1977 to 1980 at the Collège de France. What drew me to this period of Barthes’ work was a cryptic sentence from the inaugural speech that Barthes gave on 7 January, 1977 at the Collège de France: “Je crois sincèrement qu’à l’origine d’un enseignement comme celui-ci, il faut accepter de toujours placer un fantasme, qui peut varier d’année en année.” (Barthes, Œuvres complètes (hereafter OC) V, 445) [I sincerely believe that at the origin of teaching such as this we must always locate a fantasy, which can vary from year to year. (Barthes 1982, 477)] It was primarily the no- tion of the fantasy (or ‘phantasy’ or ‘phantasm’ as fantasme is some- times translated) that intrigued me here, and I was also very curious about the manner in which Barthes used these fantasies in his own courses. And I was fortunate, for only recently was this final chapter of Barthes’ work made available to a wider audience. The first two courses—Comment vivre ensemble (How to live together) and Le Neutre (The Neutral)—appeared in 2002, thanks respectively to Claude Coste and Thomas Clerc, and in 2003 the final two lecture se- ries were published together under the title La Préparation du roman I et II (The Preparation of the Novel I & II), thanks to Nathalie Léger. For more than twenty years, scholars had to avail themselves of brief summaries in the annuaire du Collège de France, references in a few interviews and a couple of lectures or articles that revisited some ele- ments from the lecture series. It was therefore logical that the Cours played a marginal role in the reception of Barthes’ oeuvre, which is why at the start of my research I found myself on terra incognita. What frustrated me the most was that Barthes himself, in his own les- sons, never really made clear what the notion of the fantasy—which was so important to his literary theory—actually meant. Nevertheless, I remained convinced that Barthes’ notion of fantasy was particularly suitable to conceive the intensity of the reading experience, an inten- sity such as the one incarnated for me in the painting of the Arntzenius sisters. At the same time I quickly came to understand that I would first have to make a detour around a series of thinkers who could help me clarify Barthes’ idiosyncratic interpretation of the fantasy.