The Pepper Trail: History and Recipes from Around the World PDF

Preview The Pepper Trail: History and Recipes from Around the World

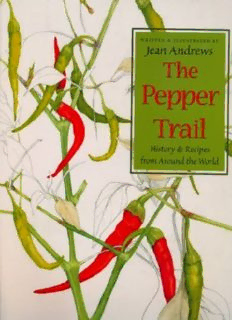

Page i The Pepper Trail History and Recipes from Around the World Page ii Page iii The Pepper Trail History & Recipes from Around the World Written & Illustrated by Jean Andrews THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS PRESS Denton, Texas Page iv Copyright © 1999 by Jean Andrews All rights reserved 5 4 3 2 1 Permissions University of North Texas Press PO Box 311336 Denton TX 762031336 9405652142 Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data Andrews, Jean. The pepper trail: history and recipes from around the world/ written and illustrated by Jean Andrews p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 1574410709. 1. Cookery (Hot peppers) 2. Hot peppers. I. Title. TX803.P46A52 1999 99222244 CIP 641.6'384—dc20 Printed in Canada Maps by cartographer John V. Cotter, Ph.D. Design by Mary Ann Jacob Page v DEDICATION To Isabella of Castile, feminist Queen of Spain whose intuition and support of the Columbus quest made the discovery of peppers possible; a remarkable woman who spent more time on the battlefield than in the kitchen Page vii CONTENTS Foreword ix Part I The Pepper: How Our Food Got Hot Which Way Did they Go? 3 The First Hot Spots 18 Hot Spots Today 34 What Is a Pepper? 50 Look at Me: Cultivar Descriptions 59 Part II Preparation & Recipes Cooking with Peppers: How to Choose 'Em and Use 'Em 85 Befores, Soups, and Salads 103 Meat, Fowl, and Seafood 123 Vegetarian 155 Sauces 169 Breads 187 Desserts 193 Preserves and Condiments 201 Notes 221 Bibliography 233 Subject Index 243 Recipe Index 251 Page ix FOREWORD This is not your everyday cookbook. It is a cultural history of a food—with recipes—put together by an inquisitive scholar, gardener, cook, traveler, and artist who fell in love with peppers more than twenty years ago. During that time I attempted to learn what they are, where they came from, where they moved, and how they affected the cooking in the places they went. I thought others might be interested in what I discovered. It is written in two parts—the history, geography and background in the first and the cookery in the second, with a bibliography for those who want more. It bombards the reader with an awesome amount of data pieced together from various fragments of information into an overwhelming historical, and geographical study of the pepper pod. It won't hurt my feelings if you just skip to the recipes, but you'll miss a hot story. Peppers: The Domesticated Capsicums or Peppers I, my first book about the genus Capsicum, probably told the average reader more than one ever wanted to know about peppers. However, that book barely touched on the food aspect of peppers and had but twentyfour recipes. Since then I have not only revised and updated that book but I have also traveled the pepper trail, from Bolivia to the Far East, Tibet to Timbuktu and back, tracking the pungent pod. It is my intent in this book to take up where the first book left off and again tell you more than you might want to know, but this time about how and why the American capsicums moved from their prehistoric Bolivian place of origin and traveled around the world affecting the foodways of both hemispheres, and also, how you, patient reader, can hone your Capsicum cooking skills. To me, it is a fascinating story. Bear with me as I share some of my findings. Not all of the fascinating happenings (both appealing and appalling) on my pepper travels are here—maybe that's another book! As I delved deeper into the directions taken by the Capsicum peppers after Christopher Columbus discovered them, it appeared to me that as peppers followed the ancient trade routes they had a great effect on the cuisines of the lands along the way. Once capsicums reached the Old World they fell into the hands of spice merchants. I began to wonder why the spice trade went one way and not another five hundred years ago? how it went and what it went in? who carried it? why some people responded to the introduction of peppers and others didn't? why cuisines have certain characteristics and not others? and on and on. These questions took me not only to libraries, where I found much about the spice trade but only a little about the early movements of peppers. They also took me to many countries along the pepper trail including much of Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, and Monsoon Asia—India, Nepal, Bhutan, Tibet, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Indonesia—plus Xinjiang, Sichuan and Hunan in China as well as Latin America. Our swift little pod had done a significant part of its travel within the first fifty years after Columbus brought it back to Spain, which makes for a very longago story in times very, very different than those we now live in. The more I looked into this saga, the more I became convinced Page x that the presumptive pepper trail by which Columbus took the American plant to Spain and whence they progressed to Europe was not the only pathway followed into Europe and the Middle East. So I set out to learn what I could about our peripatetic pod. At the onset I learned that the historical background for studying Capsicum cookery is complex. In most peppery food areas throughout the world, political and economic systems that consisted of either a small local privileged upper class or conquering Europeans, attempted to dominate the daily lives and actions of the native masses. This form of class system deeply affected the cuisine, creating a division in the quantities and varieties of food consumed by different sections in the same populace, forming—by force, in the case of slavery—the food patterns of large populations. Within most of these cultural groups, religion added its food taboos. These factors combined to produce cuisines unlike our typical AmericanizedEuropean cookery. I also discovered that in spite of the necessity for every human of whatever race on earth to eat regularly, little has been written concerning the foodways of various culture groups in relation to their total cultural history. There are excellent food books like Food in Chinese Culture edited by K. C. Chang, but thumbing through book after book on history and culture of a particular group, one finds chapters on such topics as: racial composition, political organization, economic life, family, philosophy, religion, science, art, literature, recreation and amusement, and secret societies, but little or nothing on foodways. Are they just taken for granted, or is it because the dayin dayout preparation and serving of family meals has always been "woman's work" and therefore considered less important? The manner in which food is selected, prepared and served is always the result of the culture in which it occurs, as indeed are the accessories and rituals that accompany the rudimentary activity of eating. Actually, I can say with a sigh of relief that I can see a growing interest in the study of foodways as a means for understanding culture. Although food is eaten as a response to hunger, it is much more than filling one's stomach to satisfy nutritional requirements; it is also a premeditated selection and consumption process providing emotional fulfillment. The way in which food is altered reveals the function of food in society and the values that society supports. In this volume I have tried to give my readers some background for the cuisines that embrace peppers but it is preposterous to attempt to describe the foodways or food culture of many groups of people in one chapter. Each paragraph begs for elaboration, qualification, and more research to round out the story. Special thanks go to the scholars who read and approved the first three chapters. Expressly Terry Jordan, ethnogeographer and author of The American Backwoods Frontier plus too many others to list, who advised on Chapter 1; Professors Alfred Crosby, author of Ecological Imperialism and The Columbian Exchange; Robert King, linguist and expert on things Indian; L. Tuffly Ellis, historian and former director of the Texas State Historical Association; Elizabeth Fernea, author and Middle East specialist; Charles Heiser, botanist and Capsicum authority who wrote Seeds to Civilization and Of Plants and Man; Billie L. Turner and Guy L. Nesom, taxonomists; Ernest N. Kaulbach, medievalist who helped with translations; Tom Mabry, plant chemist; William Doolittle, geographer, and geographer/cartographer John Cotter who drew the maps. Special thanks go to Carol Kilgore for her editing. On the few occasions when the vast libraries at the University of Texas at Austin did not contain the material I needed, the interlibrary loan staff at the Texas State Library acquired it for me. Without their diligence in digging out obscure references I could not have put this book together. To all the originators of the recipes included here, most of whom I have come to know personally, my heartfelt appreciation. Last but not least, my right arm and both of my legs for library research—UTAustin nutrition student, Tera Laird—who did not know when she agreed to be my helper how many trips she was going to make to libraries to fetch and tote the books you will find in this bibliography, plus others which had to be reviewed. I offer no apologies for any Texas bias readers of this book may discern—I am a fifthgeneration Texan and proud of it! Enjoy! Page 1 PART I— THE PEPPER: HOW OUR FOOD GOT HOT