The Pensive Image: Art as a Form of Thinking PDF

Preview The Pensive Image: Art as a Form of Thinking

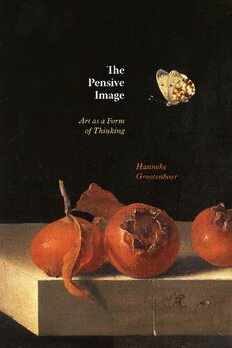

The Pensive Image The Pensive Image Art as a Form of Thinking Hanneke Grootenboer The UniversiTy of ChiCago Press · Chicago and London The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2020 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637. Published 2020 Printed in the United States of America 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 71795- 1 (cloth) ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 71800- 2 (e- book) DOI: https:// doi .org /10 .7208 /chicago /9780226718002 .001.0001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Grootenboer, Hanneke, author. Title: The pensive image : art as a form of thinking / Hanneke Grootenboer. Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020030495 | ISBN 9780226717951 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226718002 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Art—Philosophy. | Painting—Philosophy. | Art, Modern—History. | Painting, Modern—History. Classification: LCC N66 .G76 2020 | DDC 700.1—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020030495 ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1 992 (Permanence of Paper). True painting, therefore, has not only surprises, but, as it were, calls to us; and has so powerful an effect, that we cannot help coming near it, as if it had something to tell us. roger de Piles, The Principles of Painting (1708) It is necessary to rid ourselves of the idea that the concept, the content of an art- work, is something already thought, as if it already existed in a prosaic form . . . art has the purpose of bringing a not yet conscious concept to consciousness. g. W. f. hegel, Lectures on Aesthetics (1820– 1821) Contents Art as a Form of Thinking · 1 Part I: Defining the Pensive Image Chapter 1 Theorizing Stillness · 21 Chapter 2 Tracing the Denkbild · 46 Part II: Painting as Philosophical Reflection Chapter 3 Room for Reflection: Interior and Interiority · 75 Chapter 4 The Profundity of Still Life · 110 Chapter 5 Painting as a Space for Thought · 134 Painting’s Wonder · 165 Acknowledgments · 171 Notes · 175 Bibliography · 187 Index · 201 Color illustrations follow page 104. Art as a Form of Thinking Why speak of a painting, again? And why write about it? To say what in the end can never have been completely, exhaustively, said; to say just part of it, to retra- verse a slice of time in which that painting came back like a haunting enigma, a problem, a question; to keep the “minutes” of that traversal, to stockpile the readings done, questioned, revisited, inexhaustible; to produce dazzling, some- times patient, often inadequate traces of these readings. loUis Marin, On Representation Thinking involves not only the flow of thoughts, but their arrest as well. WalTer BenjaMin “To think is to see”1 In his lecture series An Introduction to Metaphysics, delivered in 1935, Mar- tin Heidegger asks, “Why are there beings at all instead of nothing?” For the philosopher, this is the most original of questions— he uses the term Ursprung— because to raise it means in fact to make a leap (Sprung) from the very basis, or ground (Ur), of our existence. A thing is a being as it exists— it is, Heidegger insists, but where exactly does the Being of this thing lie, or in what does it consist? Are we able to “see” Being? Heidegger seems to sug- gest we can when he gives one of his typical, rather overburdened examples from the visual arts: “A painting by Van Gogh. A pair of rough peasant shoes, nothing else. Actually, the painting represents nothing. But as to what is in that picture, you are immediately alone with it as though you yourself were making your way wearily homeward with your hoe on an evening in late fall after the last potato fires have died down. What is there? The canvas? The brush strokes? The spots of color?”2 This passage is different than the one that inspired the famous debate involving Meyer Schapiro and Jacques Derrida, and in any case, I want to 1