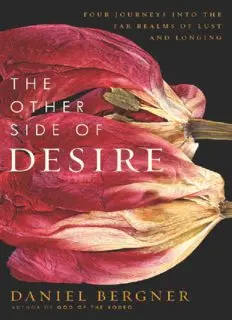

The Other Side of Desire: Four Journeys into the Far Realms of Lust and Longing PDF

Preview The Other Side of Desire: Four Journeys into the Far Realms of Lust and Longing

T H E OT H E R S I D E O F Desire D E S I R E FOU R JO U RN E YS INTO TH E FAR R E ALM S O F LUST AN D LO N G I N G D B ANIEL ERGNER CO NTENTS Introduction v I. The Phantom of the Opera 1 II. The Beacon 47 III. The Water’s Edge 97 IV. The Devotee 161 Acknowledgments 207 About the Author Other Books by Daniel Bergner Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher INTRODUCTION “What,” the people I write about often ask, “are you doing here with me?” I heard the question in Angola Prison, Louisiana’s maximum security penitentiary, where I followed the lives of men sentenced to stay locked up until their deaths, with no chance of parole. I heard it in Sierra Leone, in West Africa, where I attached myself to missionaries and mercenaries and child soldiers amid the most brutal war in recent memory. And I heard it as I sought the stories—of eros, obsession, anarchy, love—that fill The Other Side of Desire. It was four years ago that I entered the worlds of the people whose lives form the spine of this book. There was an adver- tising executive who celebrated the most conventional kind of female beauty in the billboards he created, who felt no attrac- tion to the models he cast, and who was drawn erotically, in- escapably, to amputees; there was a clothing designer and rare female sadist who searched for transcendent connection with those she wounded and enslaved; there was a traveling sales- man and devoted husband whose fetish brought him extreme vi • INTRODUCTION ecstasy and crippling abasement; and there was a band leader transfixed by his young stepdaughter. How do we come to have the particular desires that drive us, how do we become who we are sexually, whether our lusts are common or improbable? How much are we born with and how much do we learn from all that surrounds us, how much can we change and how much is locked unreachably, permanently within? These questions were part of what pulled me toward my four central characters—and toward a set of scientists immersed in studying eros. And then there was the question of how we live with our longings. A speech therapist for stroke victims, a tiny woman with a doll’s round face, with black button eyes and a slender, fragile nose, told me that if a dominant lover whispered in her ear in the right way, she could reach orgasm without touch. She wanted to be harmed. But she was tortured by her desire— she was an Orthodox Jew; her grandparents had been slaugh- tered in the Holocaust; and she couldn’t reconcile the cravings of eros with the cruelty her family had suffered. What do we do with the desires we cannot bear, the desires we or the society around us strain to restrict or strangle, whether the wanting is unusual or as typical as the yearning for new lovers that can turn otherwise happy marriages into arrangements that sometimes feel as agonizing as actual imprisonment? And what is the re- lationship between the physical and the transcendent, between the surfaces of the body and the wish to melt the bounds of self, between the forces of lust and our striving for love? Some in these stories feared they would be shunned if their private selves were known—I have changed some names and a very few identifying details in order to protect them. As for the question they asked, my answer is, always, this: I am here with you, at the far edges of experience, in the hope that your stories illuminate truths shared by all of us. PART I T HE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA J JACOB MILLER LOVED TORONTO. HE THOUGHT OF it every day. He was American, and lived in a snowy American city, but a Canadian flag, with its broad bars of red and its red maple leaf, hung in his home office. A printout of the flag, on a sheet of computer paper, was taped to the wall between his kitchen and dining room. Pasted to the rear window of his car, a flag decal hinted at his love. When he dressed casually in wintertime, he favored a letterman’s-style jacket. The leaf, big and bright, adorned the back. If he’d won the lottery, he would have retired and moved to Toronto. If he could have designed his own world, that city would have occupied his entire planet. “When we had our son, I wanted what I call a T-R name,” he said, laughing at himself. “Tristan. Troy. Trice. I didn’t tell my wife why. I didn’t tell her, ‘Because it would remind me of Toronto.’ She said, ‘I’m not naming him Tristan, kids are going to make fun of him. I’m not naming him Troy.’ She said, ‘What kind of name is Trice?’”