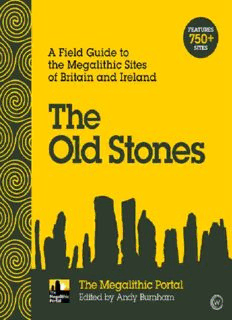

The Old Stones: A Field Guide to the Megalithic Sites of Britain and Ireland PDF

Preview The Old Stones: A Field Guide to the Megalithic Sites of Britain and Ireland

Dedication This book is dedicated to all Megalithic Portal contributors, especially those who have passed to the realms of the ancestors. Tom Bullock (Tom_Bullock), who visited more than 1,200 stone circles to create his CD-ROM guide Jack Morris-Eyton (JackME), who spent years developing his intriguing theory about shadow casting at megalithic sites (see page 184) Holger Rix (Holger_Rix), who contributed around 4,500 images and over 6,300 site pages from all over Europe Contents FOREWORD Mike Parker Pearson INTRODUCTION Andy Burnham Photogrammetry Hugo Anderson-Whymark IMAGINING PREHISTORIC LANDSCAPES Vicki Cummings West of England Fighting Moorland Enclosure in Penwith Ian McNeil Cooke Strange Experiences at Ancient Sites Rune The Rough Tor Triangle: A Theory Roy Goutté Under the Supermarket Andy Burnham The Stone Rows of Dartmoor Sandy Gerrard The Cist on Whitehorse Hill Andy Burnham The Miniliths of Exmoor Martyn Copcutt South of England Top 10 Pieces of Music Inspired by Prehistory Andy Burnham Stonehenge: Model of a Geocentric Universe? Jon Morris Stonehenge and the Neolithic Cosmos N.D. Wiseman Feasting and Monument Building Barney Harris Cat’s Brain: A House for the Living? Andy Burnham Development of the Avebury Landscape Joshua Pollard Unique Transfigurative Rock Art? Terence Meaden Archaeoacoustics Steve Marshall Midlands & East of England Dorstone Hill: A Unique Configuration of Monuments Andy Burnham Looking to the Land of the Ancestors Vicky Tuckman A Phenomenology of Shadow Daniel Brown Icknield Way: Ancient Track or Medieval Fantasy? Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews Must Farm: An Extraordinary Fenland Survival Jackie Bates Chalk Artefacts Anne Teather Insights from a Bronze Age Timber Circle Andy Burnham North of England Propped Stones David Shepherd Thornborough Archaeoastronomy Andy Burnham Neolithic Sites in the Landscape Cathryn Iliffe The Gypsey Race Chris Collyer Stone Axes Leslie Phillips Jack Morris-Eyton’s Shadow Theory David Smyth Prehistoric Rock Art in Britain and Ireland Cezary Namirski Isle of Man Wales Translating Welsh Place Names Simon Charlesworth & Stephen Rule Bancbryn Stone Row Sandy Gerrard A Phenomenological Approach to Dolmens Vicki Cummings Stonehenge and the Glacial Transport Theory Brian John Healing Stones? The Preseli Bluestones Julie Kearney Bringing the Neolithic Back to Life Martyn Copcutt Colour in the Monuments of Neolithic Europe Penelope Foreman Scotland Stone Circles John Barnatt Dowsing at Cairn Holy Angie Lake Hidden Evidence: The Lochbrow Project Kirsty Millican Top 10 Urban Prehistory Sites Kenneth Brophy The Lives of Stones Anne Tate Investigating the Forteviot Ceremonial Landscape Andy Burnham Archaeoastronomy in Western Scotland Gail Higginbottom Carved Stone Balls Julie Kearney Recumbent Stone Circles Adam Welfare Skyscape Archaeology at Tomnaverie Liz Henty What is the Lunar Standstill? Vicky Tuckman The Song of the Low Moon Grahame Gardner Excavations at the Ness of Brodgar Andy Burnham An Early Neolithic House at Cata Sand Vicki Cummings Ireland Lithic Symbolism at Drombeg Terence Meaden The Art of the Boyne Valley Robert Hensey Modified Boulders of the Cavan Burren Gaby Burns Further Reading & Resources Author Acknowledgements/Photo Credits Join the Megalithic Portal Foreword Mike Parker Pearson, Professor of British Later Prehistory at University College London Megaliths are among the most enduring remazins from our prehistoric past. Whether as single standing stones or impressive stone circles and tombs, they provide a glimpse into a vanished way of life that may seem beyond our comprehension. Yet, as Vicki Cummings points out so well in her introduction to this book, megalithic monuments represent the tip of the iceberg in terms of what has survived from thousands of years ago. Thanks to advances in archaeology, both technical and organizational, we are learning much about the people who built the megaliths. The remains that usually survive only below ground – the houses, portable material culture, nonmegalithic monuments and environmental evidence – are becoming better understood. Thanks to analyses of chemical isotopes and ancient DNA, we are learning about the people themselves – who their ancestors were, where they came from and how mobile they were. With the application of so many new scientific methods, this is an exciting time to be an archaeologist. Even as I write, new results from ancient DNA analysis are revealing that Britain’s Neolithic inhabitants show little evidence of genetic mixing with the indigenous Mesolithic huntergatherers who lived in Britain before the arrival of agriculture. These Neolithic farmers, in turn, appear to have been substantially replaced by the Beaker people and their Bronze Age descendants; current evidence suggests that, by 1500BC, only 10 per cent of people’s genes derived from the previous Neolithic population of Britain. Isotope analyses also show that these prehistoric people were highly mobile in all periods from the Neolithic to the end of the early Bronze Age. Megaliths would have been some of the few human-constructed fixed points in their lives. The growing evidence from genes and isotopes has taken many archaeologists by surprise. I am of a generation that was taught by our professors that prehistoric societies in Britain and Europe evolved largely independently without long-distance migrations. While the previous generation of archaeologists acknowledged that the domesticated animals and crops of the Neolithic originated in the Middle East, their view was that the migration theories of earlier writers such as Gordon Childe were simply wrong. Things have come full circle; the latest evidence seems to support many of the ideas put forward by Childe and his contemporaries. Yet we must remember that genes are not (pre)history and that pots are not people. We can now think about changes in lifestyle and material culture alongside population changes, instead of having to use one as a proxy for the other. Despite apparent near-total population replacement by the Beaker people, the traditions of megalith building continued across Britain and Ireland even though the Beaker people’s ancestors came from parts of Europe and Eurasia that either never had traditions of megalith building or had given them up centuries earlier. This is not to say that megalith building did not change with the coming of the Beaker people. Although megalithic monuments are often hard to date, it appears that Beaker period and Bronze Age monuments were generally smaller than those of the Neolithic. The enormous workforces required for monuments such as Avebury, Stonehenge and Silbury Hill were either no longer persuadable or simply not required. The small stone circles, standing stones, stone rows and round barrows of the Bronze Age hint at a more decentralized social and political world. Mobilizing sufficient labour to move bluestones from Wales or to dress Stonehenge’s stones was now a thing of the distant past. Although Stonehenge continued to be modified into the Bronze Age, its later stages consisted of minor rearrangements that can have required only a relatively small labour force. This book is a wonderful guide to the many megaliths and related monuments of Britain’s Neolithic and Bronze Age. The online Megalithic Portal has had a huge impact in making people aware of this rich prehistoric heritage, so it is great to see this guide to megalithic sites in book form. It will be especially valuable as a companion to visiting monuments on the ground. As more people visit such sites, so they come to better appreciate them. As we become more aware of their value, instances of thoughtless damage – as occurred at the Priddy Circles in Somerset, for example – should become rarer. We will also learn to ask new questions about the prehistoric people who erected these megaliths, and to further appreciate the value of the nonmegalithic – the more ephemeral remains that lie below the ground.

Description: