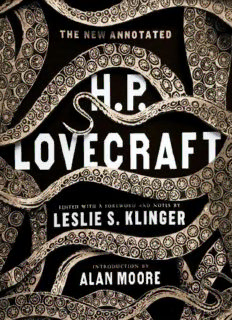

The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft PDF

Preview The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft

TO HOWARD PHILLIPS LOVECRAFT “I am Providence.” Contents Introduction by Alan Moore Foreword Editor’s Note THE STORIES Dagon The Statement of Randolph Carter Beyond the Wall of Sleep Nyarlathotep The Picture in the House Herbert West: Reanimator The Nameless City The Hound The Festival The Unnamable The Call of Cthulhu The Silver Key The Case of Charles Dexter Ward The Colour Out of Space The Dunwich Horror The Whisperer in Darkness At the Mountains of Madness The Shadow over Innsmouth The Dreams in the Witch House The Thing on the Doorstep The Shadow Out of Time The Haunter of the Dark ADDITIONAL MATERIAL Appendix 1: Chronological Table Appendix 2: Faculty of Miskatonic University Appendix 3: History of the Necronomicon Appendix 4: Genealogy of the Elder Races Appendix 5: The Works of H. P. Lovecraft Appendix 6: The “Revisions” of H. P. Lovecraft Appendix 7: H. P. Lovecraft in Popular Culture Bibliography Acknowledgements Introduction by Alan Moore W ith an increasing distance from the twentieth century and concomitant broadening of cultural perspective, the New England poet, author, essayist, and stunningly profuse epistoler Howard Phillips Lovecraft is beginning to emerge as one of that tumultuous period’s most critically fascinating and yet enigmatic figures. Lovecraft is intriguing for not only the rich substrate of astonishing and sometimes prescient ideas that is the bedrock of his work, but for the sheer unlikelihood of his ascent into the ranks of the respected U.S. literary canon: Progeny of mentally ill parents and product of an estranging cloistered upbringing, he wrote a scant few dozen short tales and some longer pieces that were published only in sensational and stigmatized pulp magazines during his lifetime, if indeed they were published at all. After his 1937 death, the earliest mainstream response was typified by critic Edmund Wilson’s withering dismissal, and even those parties most responsible for keeping Lovecraft’s name alive would often only do so by (perhaps unwittingly) misrepresenting Lovecraft’s fiction, his philosophy, and his essential nature as a human being. Furthermore, acceptance of his output as substantial literature has undeniably been hindered by his problematic stance on most contemporary issues, with his racism, alleged misogyny, class prejudice, dislike of homosexuality, and anti- Semitism needing to be both acknowledged and addressed before a serious appraisal of his work could be commenced. Such is the mesmerizing power of Lovecraft’s language and imagination that despite these obstacles he is today revered to a degree comparable with that of his formative idol Edgar Allan Poe, a posthumous trajectory from pulp to academia that is perhaps unique in modern letters. As for Lovecraft’s status as enigma, while this is implied by the perpetually expanding sphere of critical attention that attempts to penetrate his complex worldview and unusual persona, surely the real mystery lies in our continuing capacity to find him and his work mysterious. He lived for only forty-six years during an unusually well-documented period of recent history and in addition saw fit to record his daily doings, thoughts, and observations for the greater part of that short lifespan in a multitude of letters, possibly a hundred thousand such, according to some estimates, some running to extraordinary lengths and a great many of them archived or preserved in print. With even the minutiae of his dreams available; with structuralist, poststructuralist, and psychological analyses of his most juvenile or marginal material proliferating by the day, how can there be a molecule of H. P. Lovecraft’s world or circumstance or psyche that remains to be examined? What is the source of our enduring curiosity regarding this unworldly and aggressively old-fashioned individual? Born in 1890, with his first great rush of literary productivity occurring in the roaring, emblematic year of 1920, Lovecraft came of age in an America yet to cohere as a society, much less as an emergent global superpower, and still beset by a wide plethora of terrors and anxieties. The twenty years since the beginning of the century had seen the largest influx of migrants and refugees that the immigrant-founded nation had heretofore experienced, bringing with them fears that the established European settler stock might soon be overwhelmed by sprawling foreign populations or diluted by pernicious interbreeding and miscegenation. On the streets of Harlem, Greenwich Village, Times Square, and the Bowery in New York, a novel populace of highly visible and unapologetically flamboyant homosexual men (and women, albeit less noticeably) were establishing themselves, much to the consternation of the city’s moral arbiters. This was the year when women’s suffrage would be finally achieved—a period of industrial unrest and widespread strikes that seemed all the more worrying in the wake of Russia’s only recently concluded revolution. All of these prevailing fears, afflicting an extremely broad swath of conventional American society, would find expression in the writing and the ideology of H. P. Lovecraft. However, Lovecraft’s intellect and omnivorous reading habits meant that he was capable of understanding and experiencing a still wider spectrum of unease than the beleaguered average citizen. Contemporaneous advances in humanity’s expanding comprehension of the universe with its immeasurable distances and its indifferent random processes had redefined, dramatically, mankind’s position in the cosmos. Far from being the whole point and purpose of creation, human life became a motiveless and accidental outbreak on a vanishingly tiny fleck of matter situated in the furthest corner of a stupefying swarm of stars, itself but one of many such swarms strewn in incoherent disarray across black vastness inconceivable. These possibly more rarefied yet more unsettling and fundamental phobias would also be articulated in the work of the Rhode Island visionary, as his pantheon of mindless or chaotic cosmic powers or in his much-loved everyday New England landscape altered and infected by conceptions from beyond. In this light, it is possible to perceive Howard Lovecraft as an almost unbearably sensitive barometer of American dread. Far from outlandish eccentricities, the fears that generated Lovecraft’s stories and opinions were precisely those of the white, middle-class, heterosexual, Protestant-descended males who were most threatened by the shifting power relationships and values of the modern world. Though he may have regarded himself, in accordance with the view held of him by his readership and even those that knew him personally, as an embodiment of his most emblematic fable, “The Outsider,” in his frights and panics he reveals himself as that almost unheard-of fluke statistical phenomenon, the absolutely average man, an entrenched social insider unnerved by new and alien influences from without. This, it might be suggested, is the underlying reason for our ongoing absorption in his work, a fascination that seems only to increase as Lovecraft and his times recede into the past: In H. P. Lovecraft’s tales, we are afforded an oblique and yet unsettlingly perceptive view into the haunted origins of the fraught modern world and its attendant mind-set that we presently inhabit. Coded in an alphabet of monsters, Lovecraft’s writings offer a potential key to understanding our current dilemma, although crucial to this is that they are understood in the full context of the place and times from which they blossomed. This, by a circuitous route, brings us to Leslie S. Klinger’s The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft. In the previously mentioned rapidly dilating sphere of Lovecraft scholarship, it would appear that Mr. Klinger has succeeded admirably in the unenviable effort of appending Lovecraft’s oeuvre in a manner that is not redundant or repetitive, but rather complementary to the body of existing commentary. Even more notably, the welcome strategy of focusing upon the sociohistoric references in Lovecraft’s narratives—casually mentioned items or events the full import of which might easily escape the reader of today —allows us to locate this hard-to-categorize author in the context of the era that engendered him, assisted by the text’s profusion of illuminating photographic reference. If, as maintained above, an understanding of his fiction is not possible without consideration of the societal landscape that surrounded him, such an approach is surely necessary. In addition to this careful referencing of the gentleman from Providence’s times and circumstances, Mr. Klinger understands the need to study Lovecraft’s work through the variety of fine-ground lenses that are now available to us by

Description: