Table Of ContentTHE NEUROTIC TURN

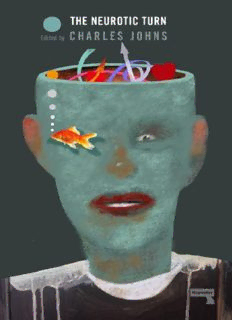

THE NEUROTIC TURN

Inter-Disciplinary

Correspondences on Neurosis

Edited by Charles William Johns

Contents

Introduction

Charles William Johns

PART ONE — PSYCHOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY: WHERE DID NEUROSIS GO?

“Neurosis can still be your comforting friend”:

Neurosis and Maladjustment in Twentieth-Century Medical and Intellectual

History

Petteri Pietikainen

The Place of Neurosis and Its Rise to Absence

John O’Donoghue

Anthroponotic Neurosis: Interspecies Conflict in

Clinical Animal Studies

Dany Nobus

The Psychology of Productive Dissociation, or What Would Schellingian

Psychotherapy Look Like?

Sean McGrath

PART TWO — PHILOSOPHY: RECONSTRUCTING, DISCLOSING AND UNBINDING

NEUROSIS

The Neurotic Turn

Charles William Johns

Conceptual Animism as Neurosis

Graham Freestone

Neurotic Situations

John Russon

Neurosis: Asymmetry and Infinity

Christopher Ketcham

PART THREE — CAPITALISM, TECHNOLOGY AND NEUROSIS

Anorexia Nervosa and Capitalism

Katerina Kolozova

Neuroses and Complexity, Alien Subjectivity and Interface

Patricia Reed

The Neurotics of Yore: Cyber Schizos vs Germinal Neuroses

Mohammad-Ali Rahebi

PART FOUR — LINGUISTICS: CULTURAL NEUROSES

“Neurotic I Am”

Benjamin Noys

Neurosis, Obsession and Dis-Identification Relief

Patricia Friedrich

Freud’s Wolf-Man in an Object-Oriented Light

Graham Harman

Acknowledgements

PART ONE

PSYCHOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY

WHERE DID NEUROSIS GO?

Petteri Pietikainen

John O’Donoghue

Dany Nobus

Sean McGrath

“Neurosis can still be your

comforting friend”:

Neurosis and Maladjustment in

Twentieth-Century Medical and

Intellectual History

Petteri Pietikainen

By the 1970s, neurosis had started to collapse. It had become an overblown,

diffuse and psychoanalyticallytinged diagnostic category that was out of time. In

1980, the publication of the third edition of the American Psychiatric

Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-III) signaled the

deathblow to neurosis as a general diagnostic category. At the same time, the

decades-old distinction between psychoses and neuroses was, by and large,

abandoned as a fundamental organizing principle in psychiatry. DSM-III

radically deconstructed the concept of neurosis and relegated it to the margins of

official psychiatry. This was a huge disappointment to the American

psychoanalysts, whose professional expertise as well as livelihood were largely

dependent on the diagnostic proliferation of neurosis (Decker 2013: 278).

The main “executioner” of neurosis was identified as Robert L. Spitzer, the

principal creator of DSM-III. In letters to editors of various medical and

psychiatric journals, the psychoanalytic supporters of neurosis voiced their

discontent at the removal of neurosis as a major diagnostic category. In 1982,

one supporter expressed his concern as a poem published in a psychiatric

journal. Spitzer replied to him in the same poetic style:

In Reply. — Peter, oh Peter, your pain is so real, the word, neurosis, has

great appeal. It tells you what the problem is not, neither psychosis nor

organic rot. How comforting it is for you to know the cause of all

mankind’s woe. If only we could be so sure that untangled conflict led to

cure. But other theories now abound, who’s to tell which of them is

sound? Bad mothering, of course, sure isn’t good, but consider these

paths to ‘patienthood’: Could bad cognitions be the hex, instead of

conflicts over sex? A transmitter lacking in your brain may lead to lots of

psychic pain. Had your neurosis Bacillus been found, in DSM-III the

term would abound. Have cheer, dear Peter, this isn’t the end, neurosis

can still be your comforting friend. Use DSM-III for a diagnostic

description, and neurosis to help with your prescription. (Spitzer 1982:

623)

Apparently, such a loss of diagnostic status caused anxiety and other neurotic

symptoms to some dedicated friends of neurosis.

My essay focuses on the intellectual and sociocultural contexts of neurosis in

the decades following World War II. Between 1945 and 1980 neurosis was

closely linked with the problem of adaptation and adjustment. A socially

disruptive failure in adjustment — maladjustment — was not only a “symptom”

that was of special importance to American psychiatry, it also attained a

diagnostic status in 1952, when DSM-I was published. In addition to its strong

appeal to the behavioural experts, the issue of maladjustment had strong

sociological and political overtones. This was because post-war American

psychiatry was fundamentally concerned with a mechanism of the individual and

collective “fitting in” to the social order and the community. Individuals who

suffered from periodic or constant maladjustment were often diagnosed with

neurosis, especially if such maladjustment was not linked with criminality or

other gross violations of social rules and norms (in which case the preferred

diagnosis was psycho-/sociopathy). For mental health professionals,

maladjustment was typically seen as the individual’s deviance from the societal

norms, or as a failure in socialization, but there were very few “psy experts” who

deliberated on the social and political aspects of mental deviance. One of them

was Erich Fromm, a German-American psychoanalyst and a critic of managerial

capitalism, and another was the British psychoanalyst and radical psychiatrist

R.D. Laing. In the second part of my essay, I will discuss the ideas of Fromm

and Laing, as well as those of three more sociologically, economically and

philosophically oriented critics of society, C. Wright Mills, J.K. Galbraith and

Herbert Marcuse. Their perceptions about the condition of (mainly American)

society provides a larger sociocultural framework of the epidemic of post-war

neurosis.

Neurosis, Social Engineering and Maladjustment

I understand neurosis as a form of medicalized distress, and as such it was

closely associated with the second wave of industrialization between circa 1870

and 1914. The “second industrial revolution” was unleashed with the help of

colonial domination of non-European regions, large-scale capitalism and new

technology, especially electricity, railways, iron steamboats, steel, petroleum and

telecommunications, such as telegraph and telephone. Industrialization is

predicated on the principle of economic and cognitive growth, hence the

premium put on education and skills in industrial societies. To a large extent,

what is loosely called “modernity” can be equated with industrial capitalism,

which brought with it population growth, urbanization, universal education,

division of labour, the strengthening of the middle class and the emergence of

the working class on the political scene.

When neurasthenia ¾ literally, “nervous exhaustion” ¾ became an extremely

popular diagnosis during the last two decades of the nineteenth century, the

Western world was experiencing the second industrial revolution. In this rapidly

changing world, what came to be called the “social question” required scientific,

rational solutions. The social question referred to the societal consequences of

industrial capitalism, including poverty, urban squalor, poor hygiene, high

mortality, physical and mental disabilities, alcoholism, suicide and political

radicalism. The authorities’ need to acquire knowledge about the social

conditions of people and about the general functioning of the social system

paved the way for the society of experts and for the “scientisation of the social”

(Etzemüller 2009).

The rise of the social sciences was one consequence of the rise of the social

question; another was the medicalization and psychologization of the human

condition. In short, the rise of neurasthenia and other neuroses is closely tied to

late-nineteenth-century and earlytwentieth-century modernity, in which science

provided empirical and statistical information about society and individuals

while science-based social planning or social engineering provided societal

regulation and stabilization in rapidly changing societies. The way I use the term

“social engineering” refers to a set of public policies designed by academically

trained experts together with policy makers with the aim of organising and

stabilising society, as well as shaping patterns of citizen behaviour. In social

engineering, social scientific, psychological and medical knowledge is applied to

various social fields, such as education, work, military, health care, social policy,

law and penal institutes, religion and urban planning. In late-nineteenth-century

Europe, the rationale of social engineering was implemented in the social

hygienic ideas and policies revolving around the social question.

In regard to an ideal citizenship in a nation state, social engineering revolved

around the key ideas of adaptation and adjustment. In the biological sciences,

adaptation, a term derived from Darwin’s theory of natural selection, refers to

the process in which the specific phenotype (e.g. size or colour) evolves for a

given external environment. By the early twentieth century, the human sciences

had borrowed the concept from biology, and it began to denote the human

capacity to learn and to rearrange social relations in response to changing

circumstances. Adaptation is related to adjustment, which refers to an active

effort by policy makers and experts to control and manage the process and

direction of social adaptation. In Western Europe and North America after

World War I, the concept of adjustment became intrinsic in the idea of rational,

apparently apolitical designing of a society in which the disadvantaged groups,

including the mentally ill, economically distressed and unskilled workers, would

become economically and socially useful citizens, or at least not harmful to

society. The normative idea of adjustment implied that citizens should learn to

be active and productive in the labour market, which in turn required efficient

health care and social policy to minimize economic inefficiency and political

tension.

The two most important criteria for successful adaptation were the citizens’

ability and willingness to work and comply with the legally sanctioned rules and

norms of society: every individual should become an industrious, morally

upright and law-abiding member of society, regardless of his or her political

affiliation. In this context, the human sciences represented what the historian Jan

Goldstein has called a “machine for the production of selfhood”: accumulating

knowledge about human behaviour and social organization could be utilized to

steer society and shape citizenship to conform to the seemingly objective

demands of the modern industrial world (Goldstein 1994). The key to

understanding the scientization of society was inclusive normalization of

deviances, rather than exclusive stigmatization or elimination of them. With

“normalization” I refer to the public policy of social adjustment in which the

parametres of “normality” and “abnormality” were set by statistics (of

criminality, mental illness, suicide, etc.) as well as by the shared understanding

of the ideal citizenship by the elite groups of society.

The goal of social engineering can be expressed by the shift from adjustment

to adaptation, from policies of external control and management to those of

selfcontrol and self-management. There were human “costs” or unintended

consequences involved in the policies of adjustment and adaptation, including

Description:We live in an age saturated with images. Video screens loop multimillion dollar ads while we sit in the back of taxis. Teenagers scavenge through public parks in search of Pokemon. Technology has created for us a new reality; one which we are still struggling to understand. Taking their cue from the