The Middle Ages and the movies: eight key films PDF

Preview The Middle Ages and the movies: eight key films

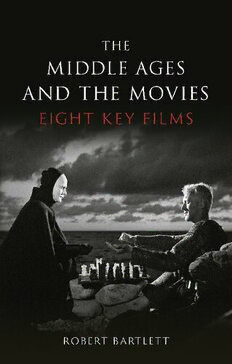

the Middle Ages and the movies the MIDDLE AGES and the MOVIES EIGHT KEY FILMS Robert Bartlett reaktion books ltd To my students at the universities of Edinburgh (1980–86), Chicago (1986–92) and St Andrews (1992–2016) Published by Reaktion Books Ltd Unit 32, Waterside 44–48 Wharf Road London n1 7ux, uk www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2022 Copyright © Robert Bartlett 2022 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 978 1 78914 552 6 CONTENTS Preface: Medieval History on the Screen 7 1 Sex and Nationalism: Braveheart (1995) 21 2 From the Page to the Screen: The Name of the Rose (1986) 49 3 Now for Something Completely Different: Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) 77 4 The Artist and the State: Andrei Rublev (1966) 105 5 Good and Bad Muslims: El Cid (1961) 131 6 Playing Chess with Death: The Seventh Seal (1957) 161 7 Heroic Leadership: Alexander Nevsky (1938) 187 8 A Silent Epic: Die Nibelungen i: Siegfried (1924) 215 Wrapping Up 243 further reading 266 Photo Acknowledgements 273 index 274 preface MEDIEVAL HISTORY ON THE SCREEN Where do we get our picture of the historical past? For many ce nturies, any detailed knowledge came from reading, or, in an oral world, listening. And what was read or listened to might, by a modern historian, be classified as either fact or fiction, tricky as that distinction is. Still today, words, printed or online, build up an image of the past for us, whether in the specialized form of the history book, or in historical novels, some of which are read (or at least bought) by hundreds of thousands of people, even, in rare cases like The Name of the Rose, by millions. So the experience of the page (including the online page), conveying information and imagery both factual and fictional, has been and continues to be a major channel for our picture of the past. Since the 1890s, however, there has been a radically different way of building up images of the past and forming ideas about it: the screen and the moving images it displays. The cinema audience, engaged in a group experience, unlike the more private act of reading, was presented with historical documentaries and historical dramas almost as soon as moving pictures were invented – there were even Joan of Arc films before 1900, for example. The stream of historical film then widened into one of the main subgenres of the motion pictures. A medium so greedy for storylines turned to actual history, and to modern 7 The Middle Ages and the Movies invented stories set in the past, and to stories based on the literature of the past, for its plots and settings. Leaving aside the many films, especially war films, set in the fairly recent past, popular subjects of historical film have been the ancient world and the so-called early modern period of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Films set in the days of the Roman Empire became so recognizable that they earned their own label, ‘sword and sandal films’, and could be parodied, as in the Coen brothers’ Hail, Caesar! of 2016, without further explanation, while the Tudors, particularly Henry viii (r. 1509–47) and Elizabeth i (r. 1558–1603), have had many screen lives. Films about the Middle Ages, the sub- ject of this book, are less common but still number in the hundreds. And, like other historical films, they are involved in a vigorous inter- play between written sources and visual realization, and between fictional and factual stories and scenes. The historical novel Ivanhoe, a best-seller by Walter Scott published in 1819 that spawned numer- ous stage adaptations including nine operas – the first such production, in 1826, with music based on Rossini – offered prime source material for the cinema. A film version of 1952 has Robert Taylor, who starred as Lancelot in Knights of the Round Table the following year, as Ivanhoe, while the young Elizabeth Taylor plays the beautiful Rebecca, the Jewish woman who helps him. Later in the same decade, a 39-episode television adaptation of Ivanhoe aired, starring in the lead role Roger Moore, who went on to be cast as James Bond, a role he played in seven films in the 1970s and ’80s. Such a transition from Romantic novel to opera to film and televi- sion has a natural logic, each incarnation with a similar menu of pageantry, exotic costume, violence, swift plot turns and love inter- est. In some ways, indeed, opera foreshadowed cinema as the great art form of spectacle. 8 Medieval History on the Screen Just as there is a constant to-and-fro between screen and page, so there is between fact and fiction. Historical fact is continually being turned into historical fiction, either in novels or in films. A very successful example is Hilary Mantel’s novel Wolf Hall, based on the life of the Tudor politician and official Thomas Cromwell and pub- lished in 2009, which won the Man Booker Prize, and was adapted for stage and television. The historian Miles Taylor even coined the verb ‘to Wolf-Hall’, meaning to create historical fiction from factual history, in a 2016 review of a book by Ferdinand Mount featured in London Review of Books: ‘Mount has written some historical fiction . . . he has Wolf-Halled his way around the French Revolution and the Crimean War.’ Hilary Mantel fictionalizes, then the screen adapts her fictionalization, so there is a complex process of multiple adap- tation here. The historical novelist reads deeply (we hope!) in the factual literature about a historical person or period and decides how that can be used in a work of imaginative literature, before the screenwriters, directors and actors transform that work into some- thing that can be effective on stage or screen. And it is in the nature of things that the image of the past conveyed in a successful film will have a far wider public than that depicted in any history book or most historical novels. This book looks in detail at eight films with a medieval setting, chosen from different decades of the twentieth century and from various countries. They exhibit differences of genre, of ideology, of the political and economic system in which they were produced, and these will be discussed, but they all have in common the attempt to represent the medieval world in that entirely modern medium, the motion picture. That medium has certain distinctive features. While one could reasonably say that both historical writing and historical film have a ‘point of view’ which can be analysed, it is a 9