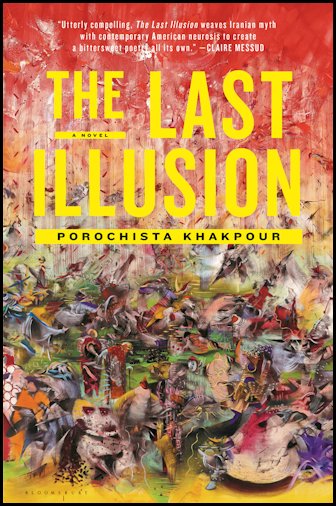

The Last Illusion PDF

Preview The Last Illusion

From the critically acclaimed author of Sons and Other Flammable Objects comes a bold fabulist novel about a feral boy coming of age in New York, based on a legend from the medieval Persian epic The Shahnameh, the Book of Kings.

In a rural Iranian village, Zal’s demented mother, horrified by the pallor of his skin and hair, becomes convinced she has given birth to a “White Demon.” She hides him in a birdcage and there he lives for the next decade. Unfamiliar with human society, Zal eats birdseed and insects, squats atop the newspaper he sleeps upon, and communicates only in the squawks and shrieks of the other pet birds around him.

Freed from his cage and adopted by a behavioral analyst, Zal awakens in New York to the possibility of a future. An emotionally stunted and physically unfit adolescent, he strives to become human as he stumbles toward adulthood, but his persistent dreams in “bird” and his secret penchant for candied insects make real conformity impossible. As New York survives one potential disaster, Y2K, and begins hurtling toward another, 9/11, Zal finds himself in a cast of fellow outsiders. A friendship with a famous illusionist who claims—to the Bird Boy's delight—that he can fly and a romantic relationship with a disturbed artist who believes she is clairvoyant send Zal’s life spiraling into chaos. Like the rest of New York, he is on a collision course with devastation.

In tones haunting yet humorous and unflinching yet reverential, The Last Illusion explores the powers of storytelling while investigating contemporary and classical magical thinking. Its potent lyricism, stylistic inventiveness, and examination of otherness can appeal to readers of Salman Rushdie and Helen Oyeyemi. A celebrated essayist and chronicler of the 9/11-era, Khakpour reimagines New York’s most harrowing catastrophe with a dazzling homage to her beloved city.

Porochista Khakpour, photo by Marion Ettlinger

Téa Obreht, photo by Beowulf Sheehan

Téa Obreht:: Reading The Last Illusion, I was particularly struck by your cast of characters—their intensity, complexity, unpredictability. I wanted to ask you about Zal: how did he find his way into your imagination?

Porochista Khakpour: My Zal is based on the Zal of Persian legend—a character in the Persian national epic, the Shahnameh, the Book of the Kings. It’s our Canterbury Tales, you might say, with the scope and reach of the Old Testament or The Odyssey—50,000 verses by Ferdowsi, written over a thousand years ago. The story I felt most connected to was the tale of Zal. It’s an outsider’s success story—an albino boy, cast off into the woods by a royal family, becomes a major Persian hero. As an immigrant child transplanted to the United States, I always felt like a misfit. I tried to carry his promise in me. My Zal, a contemporary Zal—a literalized version, raised as a bird—was also partially inspired by a feral child case in Russia. A boy who was raised among birds and could only speak in chirps had been discovered. My brain immediately filled the many holes in that story with the Shahnameh’s Zal. I wanted to tell the coming-of-age story of an anti-heroic bird boy, who, for all his oddness, becomes heroic for his normalcy. The other characters resolved out as composites of my own struggles. They all grew up in some way detached from what should have defined them—parents or nationality or history or health—and so I wanted to draw a portrait of a society without a past, individuals defined by their concept of a future. Y2K presented an ideal precipice to toe them all against, pushing them over into the unpredictably bottomless moment of 9/11. The chasms of those two events, one imagined and one horrifically real, motivated the characters with violent and irresistible gravity.

TO: As Zal’s story moves from the harrowing circumstances of his upbringing and into a perplexing new life in America, the most intense challenge he faces is the question of becoming human. The vulnerability and sincerity of his struggle is a huge emotional touchstone throughout the entire book. What was it like navigating this transformation?

PK: A good friend joked to me recently that this book is actually my memoir. I’m an outsider in every culture I’ve ever been in—Iranian, American, academic, literary, etc. All my identifiers feel a bit alien to me. It’s probably the PTSD of a childhood edited with abrupt jump-cuts and no soft dissolves. Born into war-torn, revolution-crazy Iran. Abruptly dropped into American political asylum. Unpredictably shifted from class to class. I’ve never fallen into a natural state of being—like Zal. But very few of us feel like “insiders. ” I wonder whether we entirely believe an “inside” exists. That’s the pact of real individualism, the singularity of the consciousness—we are forever on an outside of true solitariness because of the uniquely defined histories within us.

TO: In many ways, the use of magic in this story is very difficult to categorize—to call it magical realism seems too confining here, because the characters repeatedly test, and even upend, the parameters of our world in very concrete ways. Could you talk about the line between reality and supernatural, mysticism and modernity in The Last Illusion?

PK: One of my first literary loves was the magical realist Latin American literature of the twentieth century; I also deeply enjoyed European surrealists and American experimental writers. When I began imagining The Last Illusion I thought often of Toni Morrison’s advice: “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it. ” In the end, a lot of my literary influences surfaced to inform an identifiable world tempered by fantastic flourishes. At the core of this baroque, fabulist mash-up would be a simple, universal anchor: a coming-of-age love story. That element grounds the reader in something familiar. Something we accept as real. The supernatural is then freed up to become more super while remaining believably natural. Those are my favorite stories.

TO: Tell me about New York: what it means to you as a canvas, a cherished place of residence, a place both full and to be filled with stories.

PK: New York City is one of the greatest loves of my life. I grew up pinning its image to my wall. The minute I had the chance—college—I got here. And I stayed. But nothing cemented my New Yorker status more than 9/11—being in lower Manhattan, watching the events, live, outside my window, just sealed the deal. There’s a reason I write about it a lot. I love this city with the sort of love reserved for blood. I never forget what a privilege it is to share the city with some of the most incredible people in the world, New Yorkers.

TO: I’m deeply intrigued by the way you chose to address 9/11, its approach and influence on the souls that people your work. Can you discuss your process of crafting a new and intimate world around this shared piece of our history?

PK: As a child I was obsessed with a 1983 David Copperfield illusion where he made the Statue of Liberty disappear. It devastated me. I watched it just as I began obsessing over New York and of course as an immigrant, American symbols fascinated me. I remember identifying that trivial, telecast spectacle as somehow more than just magic; it was my first encounter with symbolism. Almost twenty years after witnessing that illusion, 9/11 came. It was a watermark in my life in so many ways. I was twenty-three, unemployed, confused, and suddenly thrust into real life. And the world had literally fallen down around me.

Téa Obreht’s debut novel, The Tiger’s Wife, won the 2011 Orange Prize for Fiction and was a 2011 National Book Award Finalist.

From BooklistLauded Iranian American critic and novelist Khakpour writes another gripping tale that mixes myth and history. Based on Persian folklore, The Last Illusion is the story of a feral albino boy raised in Iran until age 10 by a deranged mother who keeps him in a cage and treats him like a bird. The boy, Zal, is discovered by his grown sister and passed off to a famous American child analyst, who adopts him, takes him to New York City, and sets out to help him integrate into society. Zal takes on the streets of New York, with its myriad characters, the same way a bird might cock its head at the strangeness of human behavior, but as he grows, he longs to be normal and must fight against his instincts to be bird. Khakpour’s writing walks a line between mythical and realistic, somehow melding the two seamlessly and keeping reality in sharp focus; the reader aches for Zal, who fumbles through life as neither completely bird nor completely human. --Heather Paulson