The Human Body in the Age of Catastrophe: Brittleness, Integration, Science, and the Great War PDF

Preview The Human Body in the Age of Catastrophe: Brittleness, Integration, Science, and the Great War

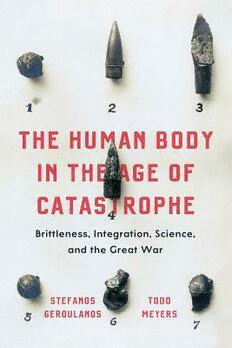

The Human Body in the Age of Catastrophe The Human Body in the Age of Catastrophe: Brittleness, Integration, Science, and the Great War Stefanos Geroulanos and Todd Meyers The University of Chicago Press :: Chicago and London The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2018 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637. Published 2018 Printed in the United States of America 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5 isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 55645- 1 (cloth) isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 55659- 8 (paper) isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 55662- 8 (e- book) doi: https:// doi .org/ 10 .7208/ chicago/ 9780226556628 .001 .0001 Names: Geroulanos, Stefanos, 1979– author. | Meyers, Todd, author. Title: The human body in the age of catastrophe : brittleness, integration, science, and the Great War / Stefanos Geroulanos and Todd Meyers. Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifi ers: lccn 2017055602 | isbn 9780226556451 (cloth : alk. paper) | isbn 9780226556598 (pbk. : alk. paper) | isbn 9780226556628 (e-book) Subjects: lcsh: Medicine—History—20th century. | Physiology— History—20th century. | World War, 1914–1918—Infl uence. | Europe— Intellectual life—20th century. | Human body—Symbolic aspects. Classifi cation: lcc r149 .g47 2018 | ddc 610.9/04—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017055602 This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48- 1992 (Perma- nence of Paper). Contents Prologue: “Why Don’t We Die Daily?” vii Part One 1 The Whole on the Verge of Collapse: Physiology’s Test 3 2 The Puzzle of Wounds: Shock and the Body at War 34 3 The Visible and the Invisible: The Rise and Operationalization of Case Studies, 1915–1 919 78 Part Two 4 Brain Injury, Patienthood, and Nervous Integration in Sherrington, Goldstein, and Head, 1905–1 934 111 5 Physiology Incorporates the Psyche: Digestion, Emotions, and Homeostasis in Walter Cannon, 1898– 1932 138 6 The Organism and Its Environment: Integration, Interiority, and Individuality around 1930 161 7 Psychoanalysis and Disintegration: W. H. R. Rivers’s Endangered Self and Sigmund Freud’s Death Drive 207 CONTENTS vi Part Three 8 The Political Economy in Bodily Metaphor and the Anthropologies of Integrated Communication 247 9 Vis medicatrix, or the Fragmentation of Medical Humanism 292 10 Closure: The Individual 316 Acknowledgments 323 Abbreviations and Archives 327 Notes 331 Index 409 Prologue: “Why Don’t We Die Daily?” In a draft of his 1926 lecture “Some Tentative Postu- lates Regarding the Physiological Regulation of Normal States,” the American physiologist Walter Bradford Can- non endeavored to outline how an organism holds itself. It functions, he contended, not organ by organ or part by part but as a stable, self- regulating whole. And yet within his thesis he could not help but contemplate the fragile complexity of self-r egulation. In the midst of all the bodily labor to maintain a delicate equilibrium, Can- non wondered, “Why don’t we die daily?”1 Cannon probably wasn’t trying to be clever. If any- thing he was being momentarily unselfconscious: having only recently returned from the study of war-r elated in- jury, he could not easily ward off a lingering astonishment that organisms do not constantly fall apart. Eager though he was to turn attention away from topics of wartime physio pathol ogy and traumatic injury, perhaps, like many of his peers he simply could not move out from under the pall that the war had spread. Physiological normality had become unimaginable without a clear accounting for catastrophe. Homeostasis, the concept Cannon invented to relay his solution to this puzzle, presented the body as fi rst and foremost a dynamic process of integration meant to avert the constant danger of collapse in an indif- ferent or hostile world. PROLOGUE viii The path to homeostasis began in earnest for Cannon with the ques- tions he raised in his 1915 book on the emotions, Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear, and Rage. The project was as much a discrete sci- entifi c endeavor concerned with bodies pushed to their limits as it was a form of social witnessing. Its central claim was that the physiological production of great emotional states is brought about by confrontation with particular aggressions and causes the discharge of chemical and nervous messengers throughout the body, forcing vital actions of sur- vival. A stimulus from the outside prompts the arousal of overwhelming emotions that change, in the short and long term, the inner composi- tion—a change of posture necessary to restore balance even in extreme circumstances. World War I provided many such circumstances. Despite having a common physiology, whether a person fought or fl ed in the face of environmental aggressions was unpredictable. Some men froze in the face of the unspeakable carnage of battle. Others ran toward the fi ght. Others ran away. When some soldiers were injured and wounds ravaged their bodies and minds, life clung to them, while others suc- cumbed to injuries that seemed minor. What did physicians and medical researchers make of all this physi- ological chaos, this inconsistency? In their conceptual and experimen- tal efforts, medical thinkers repeatedly attempted to measure up to the confusion produced by the war and to overcome their frustrating in- ability to develop a lasting semiotics of injuries and behaviors. They produced a new web of concepts that splintered existing paradigms in the social sciences and became essential for thinking about integration and collapse in economics, social organization, psychoanalysis, sym- bolic representation, and international politics. To show the fi ne detail of this labor in a conceptual-h istorical and anthropological fashion is to stage thought and experimentation as they became attuned to, and tried to anticipate— even outdo—s pecifi c conditions of the lived body in states of extreme exertion. The ability of researchers to recalibrate their thinking about this body deployed particular logics, notably of integra- tion, which led to further engagements, concepts, and theories, but also to a plethora of unstable or problematic assumptions, assertions, and systematizations. Integration, collapse, self-p reservation, crisis, catastrophe, witness- ing, evidence, unknowing— in this book we pull at a tangled thread of ideas and problems that spread across the registers of the individual and the social. In early twentieth-c entury medical science a model emerged of a body that was both brittle and tightly integrated— integrated be- cause brittle and vice versa. We write about how Cannon’s question PROLOGUE ix and his answer became possible, not just for him but for his colleagues across a series of related fi elds. We explain how particular kinds of in- jury emerged during World War I and in its aftermath, and how such in- juries found their place in the bodies and lifeworlds of wounded soldiers and doctors, and in the thinking and actions of theorists and policy makers. We describe how medical care came to be understood, however tenuously, as care of the whole individual, and how the body and its medical management stirred various rethinkings of the social role of clinical medicine. We show how these conceptual threads form around and through individual, predominantly male, bodies, how they weave together different medical thinkers and medical problems, and how they sometimes fray and are replaced by others. As Paul Veyne once suggested apropos history writing, “In this world, we do not play chess with eternal fi gures like the king and the fool; the fi gures are what the successive confi gurations of the chessboard make of them.”2 Indeed, we are drawn to the arrangements on a chessboard made up of physiological theory, wartime and postwar therapeutics, psychiatry, and conceptions of the body; these changed, and the fi gures made up new groupings over and over, and along with them created new tangles in the conceptual threads that bind them together. The en- suing knots became visible to contemporaries across several fi elds, just as they now are to us. “Case histories” presented one such knot. Across disciplines cases proliferated, commanded new directions for doctors, and became both instructive and fraught. Sometimes the case was an anecdote or narra- tive to illustrate the effects of disorder on an individual level. For the American neuropsychiatrist E. E. Southard, cases came from the clinical accounts of others, and had to be compiled, aggregated, condensed, and sorted to refi ne the taxonomy of disorder toward clinical and adminis- trative ends. At other times, as the English neurologist Henry Head and the German neuropsychiatrist Kurt Goldstein recognized, each case, male or female, young or old, represented an individual, a damaged world in need of meticulous care, and even the category “case” needed to be reinvented almost with each patient they studied. Another knot to untie was “shock,” a major contributor to mortal- ity during World War I and perhaps the exemplary whole-b ody injury. Shock seemed at fi rst to bind together everything from open wounds and cerebellar lesions to psychic trauma as it ravaged the injured body that sought to stabilize itself. But this was not so. Cannon, the English physiologist and pharmacologist Henry Dale, and their counterparts on the Royal Army Medical Corps Committee on Shock found in it an