The Heart Is a Shifting Sea: Love and Marriage in Mumbai PDF

Preview The Heart Is a Shifting Sea: Love and Marriage in Mumbai

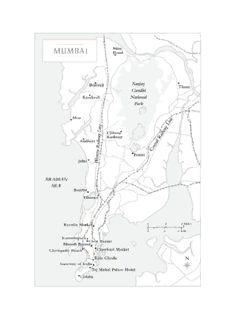

Dedication To my dad and stepdad Epigraph HERMIA: O hell! to choose love by another’s eyes. LYSANDER: Or, if there were a sympathy in choice, War, death, or sickness did lay siege to it, Making it momentary as a sound, Swift as a shadow, short as any dream . . . The jaws of darkness do devour it up. So quick bright things come to confusion. —William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream Contents 1. Cover 2. Title Page 3. Dedication 4. Epigraph 5. Author’s Note 6. Map of India 7. Map of Mumbai 8. Cast of Characters 9. Prologue: Mumbai, 2014 10. Devotion: Maya and Veer, 1999 to 2009 11. Produce a Child, and God Smiles: Shahzad and Sabeena, 1983 to 1998 12. A Suitable Match: Ashok and Parvati, 2009 to 2013 13. Illusions: Maya and Veer, 2010 to 2014 14. Fire in the Heart: Shahzad and Sabeena, 1999 to 2013 15. Skywatching: Ashok and Parvati, 2013 to 2014 16. In Time: Maya and Veer, 2014 to 2015 17. Moving House: Shahzad and Sabeena, 2014 to 2015 18. The Family Line: Ashok and Parvati, 2014 to 2015 19. Epilogue: Mumbai, 2015 20. References 21. Acknowledgments 22. About the Author 23. Copyright 24. About the Publisher Author’s Note N ine years ago, at the age of twenty-two, I moved from Chicago to Mumbai in search of adventure and a job, knowing no one in the city. I lived there for nearly two years. During that time—because I was restless and homesick—I stayed with half a dozen couples and families across the city and met many more. This is where my interest in the Indian love story began. In Mumbai, people seemed to practice a showy, imaginative kind of love, with an eye toward spectacle. Relationships were often characterized by devotion, even obsession, especially if two people could not be together. This kind of love played out on the movie screens, but it was also deep in the bones of India’s stories, in the Hindu scriptures and the Bhakti and Sufi devotional poems. I was young, and drawn to the drama. It was also a kind of love I admired, because it seemed more honest and vulnerable than what I knew. My parents divorced when I was very young, and after watching my father’s two subsequent marriages fall apart, I thought that perhaps this devotional quality was what they’d been missing. When I arrived in Mumbai after my dad’s third divorce, the city seemed to hold some answers. Out of all the people I met in Mumbai, three couples stood out from the rest. I liked them because they were romantics and rule breakers. They dreamed of being married for seven lifetimes, but they didn’t follow convention. They seemed impatient with the old middle-class morals. And where the established rules for love did not fit their lives, they made up new ones. I began asking them questions about their marriages. I had no defined goal at first. Eventually, though, I quit my job at an Indian business magazine to write about them, drawn in by their love stories. I wanted to write about them to understand how their marriages worked. * The American journalist Harold Isaacs, who chronicled Asian life in the mid- twentieth century, once complained that Americans had only a few impressions of Indian people: as exotic (snake charmers and maharajahs), mystical (holy men and palmists), heathen (cow and idol worshippers), and pitiful (leprous beggars and slum dwellers). Isaacs was writing fifty years ago, but it seems that not much has changed since. The same tired stereotypes are still trotted out by Westerners. With a country as large as India, it is tempting to oversimplify. And in Mumbai, City of Dreams, it is easy to overromanticize. In reality, India is too big and diverse for generalities. It is home to a sixth of everyone on Earth and a bewildering array of languages, religions, castes, and ethnicities. And Mumbai is an unpredictable city. I was reminded of this when I returned five years after my accident and found things were not as I remembered. At home in Washington, DC, I had regularly questioned whether I was fit to write a book about Indian marriages. I wasn’t Indian, or married. But as the years passed, I saw that the book I wanted to read about India—that I wanted Americans to read about India—did not exist. Ultimately I decided to approach the subject the only way, as a reporter, I knew how: to go back to Mumbai armed with a dozen notebooks, a laptop, and a recorder. When I landed in Mumbai in 2014, the city, save for its skyline—which had more malls and high-rises—looked much the same. The people I knew did not. Their marriages did not. They were calling old lovers. They were contemplating affairs and divorce. And the desperate attempts they were making to save their marriages, by having children, in at least one instance, were efforts I recognized from my own family. Within each couple, one partner had begun dreaming of a different life while the other was still moved by old ideas. Where before their love stories had dazzled me, now they struck me as uncertain. I tried to make sense of what had changed. “Cities don’t change,” an editor in Mumbai told me with a sigh. “People do.” It was not just them. Indian historian Ramachandra Guha said that India is undergoing not one, but multiple revolutions: political, economic, urban, social, and cultural. In Europe and America, these revolutions were staggered. In India, these changes in cities and in people are happening all at once. And they seem to be upending the Indian marriage. Nowhere are these shifts happening faster than in Mumbai, India’s most frenetic city. And in no part of society is it causing more pain than among India’s middle class, which does not have the moral freedom of the very rich or very poor. Certainly, for all three couples I followed, the opinions of family, friends, and neighbors mattered very much. People will talk was a phrase I often heard when I asked why they didn’t do what they wanted. That, and: What you dream doesn’t happen. And yet I found our conversations would often end in dreaming, as they spoke of hopes for a bigger house, a better job, a trip to Kashmir, getting pregnant, falling in love again, or moving somewhere far away. Or they spoke of how their dreams had been deferred but would surely someday belong to their children. * This is a work of nonfiction. I began writing it when I first met these people in 2008, but the bulk of the reporting was done when I returned to them in 2014 and 2015. For months, I lived, ate, slept, worked, and traveled alongside them. We mostly spoke in English, though sometimes in simple Hindi. They spoke in both languages and others among themselves. I was present for many of the scenes detailed in these pages, but the majority that took place in the distant past were reconstructed based on interviews, photographs, e-mails, text messages, diary entries, and medical and legal documents. I interviewed each couple separately and together, formally and informally, over hundreds of hours. Even when I was not in India, we spoke constantly. So much that their intimate world in Mumbai often felt more real to me than my life in DC or New York. Despite the vast physical and cultural distance between us, it felt as if we were still in the same room. It was rare that I did not hear from one or several of them every day, often in a flood of messages: recent medical reports; news of a fight at home; photographs of children clowning around before bed. All the names of the people I wrote about in this book have been changed to protect their privacy. The names I’ve used were either chosen by them or are analogous in some way to their real names. In India—as in many places—names carry meaning. In all instances, I have favored the Hindi, Urdu, Arabic, and other foreign- language spellings that the people use themselves. I have also used the English translations of the Quran, Mahabharata, and other religious and sacred texts that they keep at home. This book could not have been written without the generosity of these three couples. In Mumbai, people will discourage you from saying thank you, but I am enormously grateful for how they opened their homes and their lives to me, even when it did not make them look good or wasn’t easy. I hope that this book honors their trust in me. In the end, these are three love stories among millions. I cannot pretend that they represent the whole of India, of Mumbai, or even of the city’s contemporary middle class. But, as a well-known Dushyant Kumar poem says, it is when pain grows “as big as a mountain” that walls quake, foundations weaken, and hearts change. I am certain these couples are not alone in their pain, or in their dreaming.

Description: