Table Of Contentbie

SACRAMENTO PUBLIC LIBRARY

3 3029 0iUsi 3187 9554

anging people for small crimes as

well as grave, the Bloody Penal

Code was at its most active

between 1770 and 1830. Some

7,000 men and women were executed on

public scaffolds then, watched by crowds

of thousands. Hanging was confined to

murderers thereafter, but these were still

killed in public until 1868. Clearly the

gallows loomed over much of social life

in this period. But how did those who

watched, read about, or ordered these

strangulations feel about the terror and

suffering inflicted in the law’s name?

What kind of justice was delivered, and

how did it change?

This book is the first to explore what a

wide range of people felt about these

ceremonies (rather than what a few famous

men thought and wrote about them). A

history of mentalities, emotions, and

attitudes rather than of policies and ideas,

it analyses responses to the scaffold at all

social levels: among the crowds which

gathered to watch executions; among

‘polite’ commentators from Boswell and

Byron on to Fry, Thackeray, and Dickens;

and among the judges, home secretary, and

monarch who decided who should hang and

who should be reprieved. Drawing on

letters, diaries, ballads, broadsides, and

images, as well as on poignant appeals for

mercy which historians until now have

barely explored, the book surveys changing

attitudes to death and suffering, ‘sensibility’

and ‘sympathy’, and demonstrates that the

long retreat from public hanging owed less

to the growth of a humane sensibility than

to the development of new methods of

punishment and law enforcement, and to

polite classes’ deepening squeamishness and

fear of the scaffold crowd.

This gripping study is essential reading for

anyone interested in the processes which

have ‘civilized’ our social life. Challenging

many conventional understandings of the

period, V. A. C. Gatrell sets new agendas for

all students of eighteenth- and nineteenth-

century culture and society, while reflecting

uncompromisingly on the origins and limits

of our modern attitudes to other people’s

misfortunes. Panoramic in range, scholarly

in method, and compelling in argument, this

is one of those rare histories which both

shift our sense of the past and speak

powerfully to the present.

Mn

CENTRAL LIBRAR'

| DEC I994 |

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in 2022 with funding from

Kahle/Austin Foundation

https://archive.org/details/hangingtreeexecu0000gatr

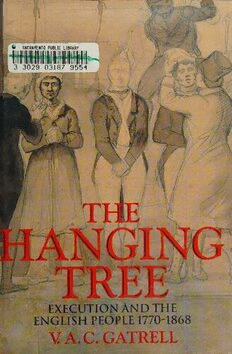

THE HANGING TREE

THE

HANGING

TREE

“pe8p xeed

Execution and the English People

1770-1868

Nem pued @ whG eAvleRellse y

OXFORD-UNIV ERSLELY PRESS

1994

Oxford University Press, Walton Street, Oxford oxz 6DP

Oxford New York

Athens Auckland Bangkok Bombay

Calcutta Cape Town Dar es Salaam Delhi

Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madras Madrid Melbourne

Mexico City Nairobi Paris Singapore

Taipei Tokyo Toronto

and associated companies in

Berlin Ibadan

Oxford ts a trade mark of Oxford University Press

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press, New York

© V. A. C. Gatrell 1994

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press.

Within the UK, exceptions are allowed in respect of any fair dealing for the

purpose of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted

under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, or in the case of

reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of the licences

issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning

reproduction outside these terms and in other countries should be

sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press,

at the address above

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Gatrell, V. A. C., 1941-

The hanging tree... execution and the English people 1770-1868 /

V.A.C. Gatrell.Data available

p. cm.

Includes index.

1. Capital punishment—Great Britain—History.

2. Executions and executioners—Great Britain—History.

3. Hanging—Great Britain—History.

HV8699.G8G38 1994 364.6'6'0941—dc20 94-4108

ISBN o-19-820413-2

ils} Se 7 GD) IK) ah 2

Set by Hope Services (Abingdon) Ltd.

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

the Bath Press, Avon

PREFACE

It may help to explain some of this book’s peculiarities if I say at once

that it grew out of a chance discovery. One day I was working in the

Public Record Office on something quite different when tedium and a

passing curiosity moved me to order from the Home Office catalogues

a volume of judges’ reports, then unknown to me. I chose the year 1829

at random. The volume fell open at a thick dossier of petitions and

papers which I was soon reading with the avidity of one who knew that

he really ought to be reading something much less interesting. It was

about a rape case set in the iron-making village of Coalbrookdale in

Shropshire. A poor man called John Noden had for several years been

courting a young woman, Elizabeth Cureton. One June evening he

knocked at her cottage window after her parents had gone to bed. She

let him in, and soon the couple were having sex on the parlour floor. A

few days later she claimed that he had raped her. She prosecuted him at

the Shrewsbury assizes, and he was tried, convicted, and sentenced to

hang. The papers I read were about the Coalbrookdale community’s

efforts to persuade the judge, the home secretary, and George IV to give

Noden a royal pardon.

The dossier’s vividness and complexity surprised me. It contained the

judge’s transcript of the trial; two huge parchment petitions signed by

hundreds of local ironmasters, professionals, and tradesmen; affidavits

from neighbours and ex-lovers telling detailed stories about Elizabeth

Cureton’s earlier sexual adventures; the local doctor’s opinion that this

was no rape but only a ‘sweetheart matter’ gone a little wrong; and the

correspondence between the judge and the home secretary, Robert Peel,

who would decide whether to let Noden die. The whole amounted to

some 12,000 words. I found this Hardyesque tragedy poignant and

entrancing. Unexpectedly, the normally opaque sexual life of a long-ago

community was opened up to me. Also opened was the way the com-

munity related to a penal code which hanged people for rape and many

offences beside, and the casual way great men made life-and-death deci-

sions. I photostated the documents, visited Coalbrookdale (the locations

are astonishingly intact), and, for my own pleasure only, wrote up the

microhistory which became Part V of this book.

Then one thing led to another, as usually happens. Reading more

deeply into the petition archive, I discovered a mountain of appeals for

Vv

PREFACE

mercy, untouched since they had been bound in volumes or tied in

pink-ribboned bundles nearly two centuries ago. Unknown to histori-

ans, there were a couple of thousand for each year of the 1820s alone.

Most were submitted by or on behalf of humble people who faced

death or transportation for transgressions large or small, real, imagined,

or unsatisfactorily proved. The lucky ones got the support of middle-

class or gentry patrons: then dossiers were often thick, stories detailed,

and opinions about unjust trial or excessive punishment confidently

advanced. Even the weakest appeals—scratchily penned, thinly sup-

ported, signed by crosses—quivered with emotion. Humble people and

their supporters pleaded for the fair hearing denied to them in court, for

life itself, or for reprieve from exile across the world. Beneath the formal

deference there were fear and desperation, sometimes indignation and

disbelief, and occasional anger too. Thus I was propelled into the felt

lives of men and women entrammelled by harsh law who had no other

historical voices than these. It was a distorted view I gained: I was read-

ing about the law’s failures rather than about the many cases satisfac-

torily dealt with. But the tone of these appeals matched my own

mounting incredulity at the fates which befell these obscure people and

at the slap-happy justice which sent them to scaffolds or exile for puny

as well as casually tried crimes.

At first my reading aimed only to set Cureton’s and Noden’s story in

context, but slowly the context became my main subject and their story

just one episode in it. As other stories pressed upon me, it became clear

that for many thousands of those past people the law was neither an

ideal nor something to which consent was spontaneously given, but an

arena of unequal negotiation and despair; moreover, it was knitted into

their lives and could shape destinies irretrievably. This realization took

me a long way from the detached kinds of criminal justice history

which historians have recently debated. It left me with a diminished

interest in how far ancien régime criminal law expressed class interests,

for instance, or contrarily in the tacit exculpations of the law which

more conservative historians have advanced. It seemed obvious from

my low angle that rich and strong people used the law to rule weaker

and poorer people, even if criminal law had other faces and could do

nicer things than that. What counted was that these stories fired me

with a taste for the lived experiences of past people which criminal jus-

tice historians have meanly served. It was an emotional and imaginative

engagement with their plights that pushed me forwards, and at last it

took me into a history of emotion itself.

Vi