The Greeks in Asia PDF

Preview The Greeks in Asia

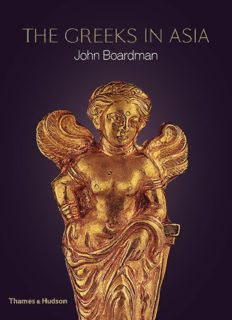

Indian gold finial inscribed OEA or 'goddess'. See PL. XXXVI. For JULIA About the Author John Boardman is Professor Emeritus of Classical Archaeology and Art at Lincoln College, Oxford. His previous books for Thames & Hudson, published over a period of fifty years, include: The Greeks Overseas; The World of Ancient Art; The Archaeology of Nostalgia; and multiple volumes in the World of Art series: Greek Sculpture; Athenian Red Figure Vases (volumes on the Archaic Period and the Classical Period); Athenian Black Figure Vases; Early Greek Vase Painting; Greek Art; and Greek Sculpture (with volumes on the Archaic and Classical periods). He is also a joint author of The Oxford History of the Classical World, The Oxford History of Greece and the Hellenistic World, and The Oxford History of the Roman World. Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include: The Greeks Overseas Their Early Colonies and Trade Persia and the West An Archaeological Investigation of the Genesis of Achaemenid Art The Making of the Middle Sea A History of the Mediterranean from the Beginning to the Emergence of the Classical World The Great Empires of the Ancient World Art & Archaeology of the Greek World A New History, c. 2500 – c. 150 BCE www.thamesandhudson.com www.thamesandhudsonusa.com Contents Preface 1 Greece and the east: beginnings Eastern origins Greeks going east 2 Greeks and Achaemenid Persia The confrontation Greeks in the Persian Empire The view from home The view from Homeric heritage 3 Greeks and Alexander ‘the Great’ The invasion of the Persian Empire Into Asia The Hellenistic heritage: 3rd to 1st centuries BC 4 The new Greek kingdoms in the east The kingdoms Their cities and arts Their coinage 5 Greeks and their arts in Central Asia Greeks and nomads: Scythians, Sarmatians The Yuehzhi and Tillya Tepe The farther east 6 Greeks and their arts in India The Mauryans and Buddhism The Sunga dynasty Taxila and Gandhara Greek and/or Roman – a memo The ‘Gandhara style’ in sculpture 7 Greeks, Romans, Parthians and Sasanians: before Islam Epilogue: myth, history and archaeology Abbreviations Notes Sources of illustrations Acknowledgments General index Index of places Preface In 1948 I met an elderly Greek man on the island of Naxos who said he had been with General Kitchener at Khartoum. As a boy he was helping his father sell lemonade to the British troops, undercutting the prices of the local Arab shopkeepers. The episode seemed typical of that Greek private enterprise and success far from home which was as apparent in antiquity as it is today, commercial rather than militant or imperial – consider Greek millionaire shipowners. It may be that this quality was one imposed by the relative poverty of the homeland. When the first Greek-speakers approached the Mediterranean from the north they found themselves ushered into a peninsula whose southern extremity was far less well provided with arable or pastoral plains than most of the other countries bordering the Mediterranean; not at all like Italy or Spain. It inevitably led to a complex of independent and often competitive states rather than a united country, and this was apparent already under the Mycenaean Greeks in the Bronze Age, with their separate kingdoms and fortress capitals. Many Greeks took to the seas and looked to improve their fortunes elsewhere. The ancient world was a relatively small place: Indian cinnamon could be found in the Heraion of Samos in the 7th century BC, but had travelled hand-to-hand;1 amber arrived from the Baltic. But the Greeks would soon learn the merits of distant travel for themselves. They had come from the north and east originally.2 Their presence in Greece, as what we call Mycenaeans, already provided opportunities to demonstrate their readiness to look both east and west, to Anatolia, to Cyprus, to Italy. Barely three centuries after the fall of the Mycenaean world in around 1200 BC their attention again inexorably turned away from the homeland. To the west they were partly looking for new homes, but were mainly acquisitive of the products and wealth of peoples of, by comparison, relatively modest cultural accomplishment and no threat. The results were to mutual benefit: the Greeks grew richer and found some new homes; the westerners were introduced to a wider world for their produce, to a monetary economy, to literacy, and to an art that could express narrative explicitly, after some centuries of relative stagnation. They were not physically threatened. This is not quite ‘colonization’ in the modern sense of the word, but there are points of comparison and any sensible scholar or student is not misled by use of the word. In the eastern Mediterranean the Greeks reintroduced themselves to the heirs

Description: