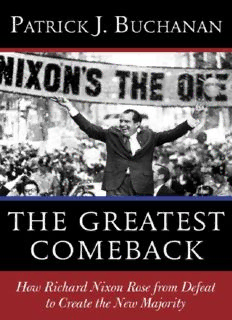

The Greatest Comeback: How Richard Nixon Rose from Defeat to Create the New Majority PDF

Preview The Greatest Comeback: How Richard Nixon Rose from Defeat to Create the New Majority

A A LSO BY THE UTHOR The New Majority Conservative Votes, Liberal Victories Right from the Beginning The Great Betrayal A Republic, Not an Empire The Death of the West Where the Right Went Wrong State of Emergency Day of Reckoning Churchill, Hitler, and “The Unnecessary War” Suicide of a Superpower Copyright © 2014 by Patrick J. Buchanan All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Crown Forum, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York. www.crownpublishing.com CROWN FORUM with colophon is a registered trademark of Random House LLC. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Buchanan, Patrick J. (Patrick Joseph), 1938– The greatest comeback / Patrick J. Buchanan. — First edition. pages cm 1. Presidents—United States—Election—1968. 2. Nixon, Richard M. (Richard Milhous), 1913–1994. 3. United States—Politics and government—1963– 1969. 4. Republican Party (U.S. : 1854–)—History—20th century. I. Title. E851.B83 2014 324.973′0904—dc23 2014007614 ISBN 978-0-553-41863-7 eBook ISBN 978-0-55341864-4 Unless otherwise designated, all photographs are from the author’s collection. Jacket design by Jess Morphew Jacket (front) photograph by Dick Halstead/Getty Images v3.1 TO SHELLEY, my wife of forty-three years who was there—right from the beginning C ONTENTS Cover Other Books by This Author Title Page Copyright Dedication INTRODUCTION: The Resurrection of Richard Nixon 1. A Loser—in a Party of Losers 2. Rapprochement with the Right 3. Comeback Year 4. The Manila Questions 5. New Recruits Photo Insert 1 6. The Six-Day War—and After 7. “Year of the Dropouts” 8. Assassinations and Anarchy Photo Insert 2 9. The Wild Card 10. Montauk and Miami Beach 11. At the “Comrade Hilton” 12. Hearing Footsteps POSTSCRIPT ACKNOWLEDGMENTS APPENDIX PARTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY I NTRODUCTION The Resurrection of Richard Nixon BARRING A MIRACLE his political career ended last week. —Time ON NIXON (NOVEMBER 16, 1962) “BUCHANAN, WAS THAT you throwing the eggs?” were the first words I heard from the 37th President of the United States. His limousine rolling up Pennsylvania Avenue after his inaugural had been showered with debris. As my future wife, Shelley, and I were entering the reviewing stand for the inaugural parade, the Secret Service directed us to step off the planks onto the muddy White House lawn. The President was right behind us. As he passed by, Richard Nixon looked over, grinned broadly, and made the crack about the eggs. It was a sign of the times and the hostile city in which he had taken up residence. He had won with 43 percent of the vote. A shift of 112,000 votes from Nixon to Vice President Humphrey in California would have left him with 261 electoral votes, nine short, and thrown the election into a House of Representatives controlled by the Democratic Party. In the final five weeks, Humphrey had closed a 15-point gap and almost put himself into the history books alongside Truman—and Nixon alongside Dewey. But the question that puzzled friend and enemy alike that January morning in 1969 was: How did he get here? In The Making of the President 1968, Theodore H. White, chronicler of presidential campaigns, begins with a passage from Dickens’s A Christmas Carol: “Marley was dead to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker and the chief mourner.… Old Marley was dead as a door-nail.” That Richard Nixon would be delivering his inaugural address from the East Front of the Capitol on January 20, 1969, would have been mind-boggling a few years before. This is not to say that Nixon was not a man of broad knowledge, high intellectual capacity, or consummate political skill. He had been seen in the 1950s as the likely successor to Dwight Eisenhower. As vice president, he had traveled the world, comported himself with dignity during Ike’s illnesses, survived a mob attack in Caracas, and come off well in his Kitchen Debate with Soviet dictator Nikita Khrushchev. In 1960, no one had challenged him for the Republican nomination. Yet Nixon had lost. While the election was among the closest in U.S. history, and there was the aroma of vote fraud in Texas and Chicago, Nixon was seen as a loser. He had not won an election in his own right in ten years. He had twice ridden Eisenhower’s coattails into the vice presidency. In the off-year elections of 1954 and 1958, where he had been the standard-bearer, the party had sustained crushing defeats. By the day of Kennedy’s inaugural, conservatives were shouldering aside Eisenhower Republicans to engage the Eastern Establishment of Dewey and Rockefeller in a war for the soul of the party. As Democrats had moved beyond Adlai Stevenson to a new dynamic leader, so had we—to Barry Goldwater. Back home in California, Nixon plotted his comeback. He would challenge Governor Pat Brown in 1962, go to Sacramento, and be available should the party turn again to him. Should the GOP look to a new face in ’64, a likely reelection year for JFK, he would finish one term as governor and pursue the presidential nomination in 1968. California was replacing New York as first state and the governor’s chair in the Golden State was an ideal launching pad for a second presidential run. But in 1962 Nixon had lost again. He had begun the campaign behind, but had been gaining ground when the Cuban missile crisis aborted his surge. Kennedy’s perceived triumph over Khrushchev had given a boost to every Democrat. Then came the “last press conference,” where Nixon berated his tormentors and declared himself finished with politics. “It had seemed the absolute end of a political career,” wrote Norman Mailer. “Self-pity in public was as irreversible as suicide.” Career over, Nixon packed up his family and moved to New York, the city of his old antagonist Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller. So it was that Nixon began the sixties losing to Kennedy, losing to Pat Brown, quitting politics, and moving east to practice law. He had lost his political base and seemed to have no political future. How did this politician of the forties and fifties, an Eisenhower Republican of moderate views and middle-class values, a two-time loser, emerge from a decade of assassinations, riots, sexual revolution and social upheaval, and the rise of a radical New Left and a militant New Right to win the presidency? In “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” Hemingway writes of a mystery on the mountain. “Close to the western summit there is the dried and frozen carcass of a leopard. No one has explained what the leopard was seeking at that altitude.” This book is an effort of the aide closest to Nixon in his now-legendary comeback to explain how he maneuvered through the conflicts and chaos of that most turbulent decade of the twentieth century to reach the “western summit”—and become President of the United States.

Description: