The Great Trek PDF

Preview The Great Trek

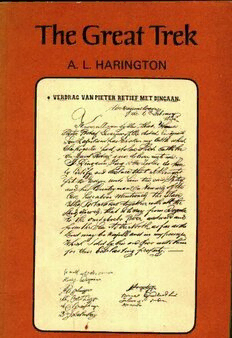

A. HA I fk • . VKBDRAC MAMf'lK TKR RgTIgLggy y~g~~, Acu~d gd 0 -z~ wc SPY'~~ ~~~~ ~ ~ a ~~M g ~rc'~p% y+g~QJt GKW~ ~Pi, ~ ~ ~ ip~ ~ .'jr~ ~kC P~ r!~ ~ ~-~ ~ ,g<~ pii ~ ~ ~ ~/ C~~~ k k kk ~ Ah yg...„~ ~PM !~~'/ye~ g- p-4- .e ~A, ~a+ c KEfGAN OOKSHOP SOUTHA FRIC4 60II SPECIALISTS 101 Nlain Road, Rondebosch THE ARCHIVE SERIES General Editors: C. P. Hill and G. H. Iiell e rea r e arin ton Senior Lecturer in History, University of South Africa, I'retoriu, South Afr ic Edward Arnold © A. L. Haringson rgb First published x9ya by Edvcard Arnold (Publishers) Ltd., ag Hill Stmet, London, vvxx gxx. ISBN o yxgx xyag x All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication rosy be reproduced, stored in a retrievalsystem, or transcnitted in any form or by any cneans, electronic, mechsnicai. photocopying, recording or otherwise, vcithout the prior permission of Edward Arnold 9 ubhshers) Ltd. ~ ARCHIVE SERIES at present eostuise thefo~ titfeee Disraeli and Conservatism by Robin Grinter. Lenin and the Russian Revolutions by F. W. Stscey. British Ixnperialism in the late x9th Century by I R. Gardiner and J. K Davidson. The Liberals and the Welfare Stateb y R. D. H. ~. Mussohni and the Fascist Ersb y Desmond Gregory. Hider aad the Rise of the Nasisb y D. M. PMlips. Britain ancl Russia ftcnn the Crnnean to the Second World War by F. W Stscey. The General Strike, xcta6b y C. L. Mowst. The Rise of the Labour Party in Great Britainb y G. R. Scxuth. Bismarck ancl the Unification of Germany by Anthony Hewison. British Trade Unionism,rgb-x9xOb y Lloyd Evans. Stalin and the ~ g of Modern Russia by F. W. Stacey. Joseph Chamberlaint Democrat, Unionist and Imperialistb y Robin Grinter. Charles Darwin and the Theory of Evolutionb y G. R, A. Withers. Chma Ill Revollctlon x91 x g9b y Myra Roper, The Reform of the Lordsb y R. D. H. Seaman. J. M. Keynesb y I G. Bxandon. The Emancipation of Women in Great Britain by 3largamt James. The Great Trek by A. L. Harington. The Origins of the Anglo-Boer Warb y S. B. Spiel' Further titlesa re in preparation. Pristedin Great Britain by Con 8' 5'yncun I td., London, Readwg usd Euhenhusc eneral Preface Today it is widely and strongly felt to be right to introduce college and school students of history to the raw materials of the subject. The aim of the Archive Series is to provide booklets of primary source material on historical topics, in a form suitable for students at various levels, including, for example, G.C.E. '0 Level' candi- dates and Sixth Forms in Britain, their equivalents in Australia and elsewhere in the English speaking world, college of education students and others. Each topic has been selected for its interest and importance. The material ranges widely: extracts from news- papers, letters, speeches, diaries, treaties, novels, statutes, and auto- biographies are all represented. Teachers, we imagine, will find the booklets useful in various ways: as a means to enrich a syllabus, as a supplement to text- books, as the basis for elementary investigation of sources them- selves, as illustrations of policies or attitudes, or merely as an occasional change from the normal routine. The series has a uniform format for ease of reference, but the author of each booklet has adopted his own plan of approach. We hope that the series will stimulate interest and increase understanding. C. P. H. G. H. F. cknowledg ments Detailed sourcfeosr e ach extract are given at the end of the bool' The Eront Cover shows a reproduction of the Retief-Dingaan treaty of 4th February, r838. The original disappeared at the time of the Anglo — Boer war. TheB ack Cover shows part of a page from the minutes of the Republic of Natalia, 6th September, »39 Both are reproduced by permission of The Transvaai Arctu«s, Pretoria. The inside front cover shows a contemporary portrait of Andries Pretorius shortly after the battle of Blood River, where he was wounded in thaer m, and isr eproduced by permission of Th«ape Archives, Cape Town. The insidbeac k cover shows a contemporary printo f a Boer hunting camp in the Karroo, and is reproduced by permission of The Transvaal Archives, Pretoria. ontents Introduction The Boers: a Nation in the Making a. The Coming of the British; as Rulers(xSo6) and as Settlers(x8ao) 3. The Causes of the Trek, and the British Attitude to it 4. The Trekkers and the Zulus in Natal 30 g. De Repgbliek ¹talia and the British 6. The Highveld Republics Sources of Extracts Intro uction South Africa is sometimes described as a 'new country', which is hardly correct, for permanent European settlement was begun at the Cape by the Dutch in the mid-seventeenth century, only a generation after the Pilgrim Fathers had sailed for North America. Though there are some obvious similarities the subsequent his- tory of the two areas has been essentially difFerent. The Cape Colony, which became South Africa, was conceived as a refreshment station, being apparently fertile and, when the planetary wind system, ocean currents and international politics had been taken into consideration, the most suitable landfall between the Texel and Batavia for the ships of the Dutch East India Company. So, in April, i65z, a party commanded. by Jan van Riebeeck, landed on the shore of Table Bay, where they were to build a fort and a hospital, plant vegetables and rear sheep and cattle. Within 6ve years the Seventeen(directors of the Company), though generally hostile to colonization, had decided to grant land to 'Free Burghers', whose pursuit of private profit would, it was hoped, make them more productive than were unenthusiastic soldiers and other employees of the Company. The period of settlement which began in x6g with the establishment of nine smallholders along the Liesbeek River, in what is now a Cape Town suburb, lasted a mere fifty years. Continuous friction and one extremely serious dispute between the settlers and local ofEcialdom... led to a momentous decision early in the eighteenth century, whereby very nearly all European immigration was ended. Imported slaves would sufBce for the colony's limited labour requirements. The ultimate effect of this was to destroy any chance whichthewestern Cape, at least, mighthavehadofbecoming'awhite man's country', in any real sense of the phrase. More immedi- ately it meant that about x65o colonists, about half of whom were of Dutch descent, the remainder German and French, had been practically marooned at the southern tip of Africa. The z,goo,ooo Afrikaners of today are almost entirely descended from them. In the early eighteenth century they were already divided, vertically, not horizontally, into three classes: the merchants and inn-keepers of De Cehapth,e wheat and wine farmers of the imme- diate interior and, beyond this settled Mediterranean corner, the 6 IMRODUCTg)g pastoralists of the open frontier. The latter, driven by their own increasing numbers and a rigidly restricted market, and encouraged by easy access to arid but seenungly unlimited land, had embarked upon a steady expansiownh ich the Company could not prevent but only follow, with futile proclamations and exhortations. It was only in the x77o's, when the erstwhile re&eshment station had acquireadva st, sparsely populated, mostly semi-desert interior two- thirds the size of France, that the outward movement of the fron- tier was eventually checked. This occurred between the Sundays and Bushman's Rivers, some goo miles to the east of Cape Town, where the farmers encountered their first serious human obstacle, the Xhosa. This was a Bantu tribe, an early Iron Age people, whose culture was based on cattle, and who were far more advanced, numerous and resilient than the Bushmen and Hottentots that the white men had hitherto destroyed, driven out or subjugated. Those same whites had long since ceased to be colonists and had become Boers', aAnfr ican people, knowing no other home, with their own (spoken) language, and a set of habits, beliefs and pre- judices that had been shaped by the human and geographical challenges they had experienced, in the solitude of their vast 6,ooo acre ranches, on the infinitely vaster Karroo. Their one book, to which they clung, was the Bible, to parts of which they paid exaggerated attention; there, as in the precepts of their elementary and only half-understood Calvinism, they found abundant rein- forcement for their deeply rooted racial prejudices. None the less, narrow and bigoted though they were it was their religion that had prevented their degenerating into barbarism. Hospitable though sometimes offensively curious, they were conservative to the core. They regarded easy access to land and a minimum of governmental control as essential parts of a free man's birthright. That happy state of affairs was terminated by the meeting with the Xhosa and the coming of the British, as rulers in x8o6, and as settlers in x8zo. The character of colonial and especially &ontier life began to change, and by the x83o's the Boers were considering a course of action which was a natural outcome of their history and way of life, a withdrawal beyond the reach of the government. Thta retreat, from the British and from change, was the Great Trek, the most significant event in the history of South A&ica to date, for it was through it that the very attitudes which had led to it, and which were enshrined in the constitutions of the Trekker repuMics, were preserved in isolation on the High Veld, to dominate the greater republic of the twentieth century. 1. The Boers: a Nation in the Making Throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the cattle farmers « the eastern and northern Cape, the future Voor- trekkers, were being moulded by their environment, until they became as much African as European, ~ cIercr>p«'<nf o <hs karroo hy an early nineteenth-century tra><lEer: From what has been said of the Karroo by the writers who have hitherto described it, the readers have been led to expec«n immense level plain like the deserts of Asia or of South America; but this is not the case. In the midst of this waste rise»me pretty lofty slate hills.... There are large spaces which are perfect plains... but these are intermixed with eminences which in other parts would appear not inconsiderable. The soil throughout is a sand mixed with clay. • • • Such a kind of soil is the product only of the ruins of nature, if I may be allowed the expression, so that there is no where any thick coat of it: in digging to a foot below the surface, we come to a hard and impenetrable stone. From these and other concomitant causes, the vegetation must, of necessity, at sii times be extremely poor, and in suuuner, when the sun has dried the soil to the hard- ness of brick, it ceases almost entirely. The ngescrnbryan+cngurn and some other succulent plants. .. alone resist the destructive nature of this inhospitable soil. It is dificult for an European to form an idea of the hardships that are to be encountered in a journey over such a dry plain hottest season of the year. All vegetation seems utterly destroyed; not a blade of grass, not a green leaf is any where to be seen; and the soil, a sti8 loam, reflects back the heat of the sun with redoubled force: a man may congratulate himself that being on horseback he is raised some feet above it. Nor is any rest from these fatigues to be thought of, since to stop where there is neither shade, water or grass, would be only to increase the evil rather than to diminis»t.