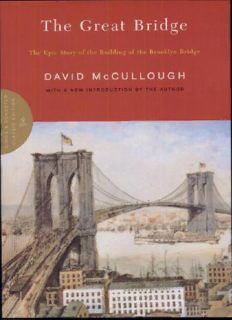

The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge PDF

Preview The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge

Also by David McCullough JOHN ADAMS BRAVE COMPANIONS TRUMAN MORNINGS ON HORSEBACK THE PATH BETWEEN THE SEAS THE GREAT BRIDGE THE JOHNSTOWN FLOOD SIMON & SCHUSTER Rockefeller Center 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, New York 10020 Copyright © 1972 by David McCullough All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. The quotation from My Life and Loves, by Frank Harris, is reprinted by permission of Grove Press, Inc.; copyright 1925 by Frank Harris, © 1953 by Nellie Harris, © 1963 by Arthur Leonard Ross as executor of the Frank Harris Estate. SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc. The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows: McCullough, David G. The great bridge. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Brooklyn Bridge (New York, N.Y.) I. Title. TG25.N53M32 624.5’5’097471 72-081823 ISBN-13: 978-0-7432-1831-3 ISBN-10: 0-7432-1831-0 Visit us on the World Wide Web: http://www.SimonSays.com For my mother and father Contents AUTHOR'S NOTE PART ONE 1. The Plan 2. Man of Iron 3. The Genuine Language of America 4. Father and Son 5. Brooklyn 6. The Proper Person to See 7. The Chief Engineer PART TWO 8. All According to Plan 9. Down in the Caisson 10. Fire 11. The Past Catches Up 12. How Natural, Right, and Proper 13. The Mysterious Disorder 14. The Heroic Mode PART THREE 15. At the Halfway Mark 16. Spirits of ’76 17. A Perfect Pandemonium 18. Number 8, Birmingham Gauge 19. The Gigantic Spinning Machine 20. Wire Fraud 21. Emily 22. The Man in the Window 23. And Yet the Bridge Is Beautiful 24. The People’s Day EPILOGUE APPENDIX NOTES BIBLIOGRAPHY INDEX AUTHOR’S NOTE WHEN I began this book I was setting out to do something that had not been done before. I wanted to tell the story of the most famous bridge in the world and in the context of the age from which it sprang. The Brooklyn Bridge has been photographed, painted, engraved, embroidered, analyzed as a work of art and as a cultural symbol; it has been the subject of a dozen or more magazine articles and one famous epic poem; it has been talked about and praised more it would seem than anything ever built by Americans. But a book telling the full story of how it came to be, the engineering involved, the politics, the difficulties encountered, the heroism of its builders, the impact it had on the lives and imaginations of ordinary people, a book that would treat this important historical event as a rare human achievement, had not been written and such was my goal. I was also greatly interested in the Roeblings, about whom quite a little had been written, but not for some time or from the kind of research I had in mind. Moreover, a good deal of legend about the Roeblings—father, son, and daughter- in-law—still persisted, along with considerable confusion. It seemed to me that the story of these remarkable people deserved serious study. It is an extraordinary story, to say the least, not only in human terms, but in what it reveals about America in the late nineteenth century, a time that has not been altogether appreciated for what it was. And beyond that I had a particular interest in the city of Brooklyn itself, having spent part of my life there, when my wife and I were first married, in a house just down the street from where Washington and Emily Roebling once lived. But early in my research another objective emerged. It became clear that this, to a large degree, was to be Washington Roebling’s book. There was, for example, that day in the library at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute when I unlocked a large storage closet to see for the first time shelf after shelf of his notebooks, scrapbooks, photographs, letters, blueprints, old newspapers he had saved, even the front-door knocker to his house in Brooklyn. No one knew then what all was in the collection. There were boxes of his papers that had not been opened in years, bundles of letters that so far as I could tell had been examined by nobody. The excitement of the moment can be imagined. The contents of the collection, plus those in another large collection at Rutgers University, both of which are described in the Bibliography, were such that they often left me with the odd feeling of actually having known the Chief Engineer of the bridge. He was not only the book’s principal character, he was the author’s main personal contact with that distant day and age. So it has also been my aim to convey, with all the historical accuracy possible, just what manner of man this was who built the Brooklyn Bridge, who achieved so much against such staggering odds, and who asked so little. I am not an engineer and the technical side of the research has often been slow going for me. But though I have written the book for the general reader, I have not bypassed the technical side. If I could make it clear enough that I could understand it, if it was interesting to me, then my hope was that it would be both clear and interesting to the reader. During my years of research and writing I have been extremely fortunate in the assistance I have received from many people and I should like to express to them my abiding gratitude. For their kindnesses and help I wish to thank the librarians at both Rutgers and Rensselaer and in particular Miss Irene K. Lionikis of the Rutgers Library and Mrs. Orlyn LaBrake and Mrs. Adrienne Grenfell of the library at Rensselaer. Herbert R. Hands of the American Society of Civil Engineers, David Plowden, Dr. Milton Mazer, Dr. Roy Korson, Professor of Pathology at the University of Vermont, W. H. Pearson, Sidney W. Davidson, J. Robert Maguire, Charlotte La Rue of the Museum of the City of New York, Regina M. Kellerman, William S. Goodwin, Allan R. Talbot, John Talbot, and Jack Schiff, the engineer in charge of New York’s East River bridges, each contributed to the research. And Dr. Paul Gugliotta of New York, architect and engineer, said some things over lunch one day years ago that started me thinking about doing such a book and later very kindly walked the bridge with me and answered many questions. I am especially indebted to Robert M. Vogel, Curator, Division of Mechanical and Civil Engineering at the Smithsonian Institution, to John A. Kouwenhoven, authority on New York City history and on James B. Eads, to Nomer Gray, bridge engineer, who has made his own extensive technical studies of the bridge, and to Charlton Ogburn, author and friend. Each of them read the manuscript and offered numerous critical suggestions, but any errors in fact or judgment that may appear in the book are entirely my own. I would like to acknowledge, too, the contribution of three members of the Roebling family: Mr. Joseph M. Roebling of Trenton and Mr. F. W. Roebling, also of Trenton, who gave of their time to talk with me about their forebears, and Mrs. James L. Elston of Fayetteville, Arkansas, who let me borrow an old family scrapbook. I am grateful for the research facilities and assistance offered by the staffs of the following: the Trenton Free Public Library; the Carnegie Library, Pittsburgh; the Brooklyn Public Library; the Long Island Historical Society, Brooklyn, and particularly to Mr. John H. Lindenbusch, its executive director; the Newport Historical Society, Newport, Rhode Island; the Library of Congress; the New York Historical Society; the New York Public Library; the Engineering Societies Library, New York; the Middlebury College Library, Middlebury, Vermont; the Baker Library, Dartmouth College; the Putnam County Historical Society and the Julia Butterfield Memorial Library at Cold Spring, New York; and the Butler County Library, Butler, Pennsylvania. I wish also to acknowledge my indebtedness to two valued friends who are no longer living—to Conrad Richter, for his encouragement and example, and to Clarence A. Barnes, my father-in-law, who was born on Willow Street on Brooklyn Heights, when the bridge was still unfinished, and who could talk better than anyone I knew about times gone by. Lastly I would like to express my thanks to Paul R. Reynolds, who provides steady encouragement and sound advice; to Peter Schwed, Publisher of Simon and Schuster, who had faith in the idea from the start; to Jo Anne Lessard, who typed the manuscript; to my children, for their confidence and optimism; and to my wife, Rosalee, who helped more than anyone. —D M C AVID C ULLOUGH

Description: